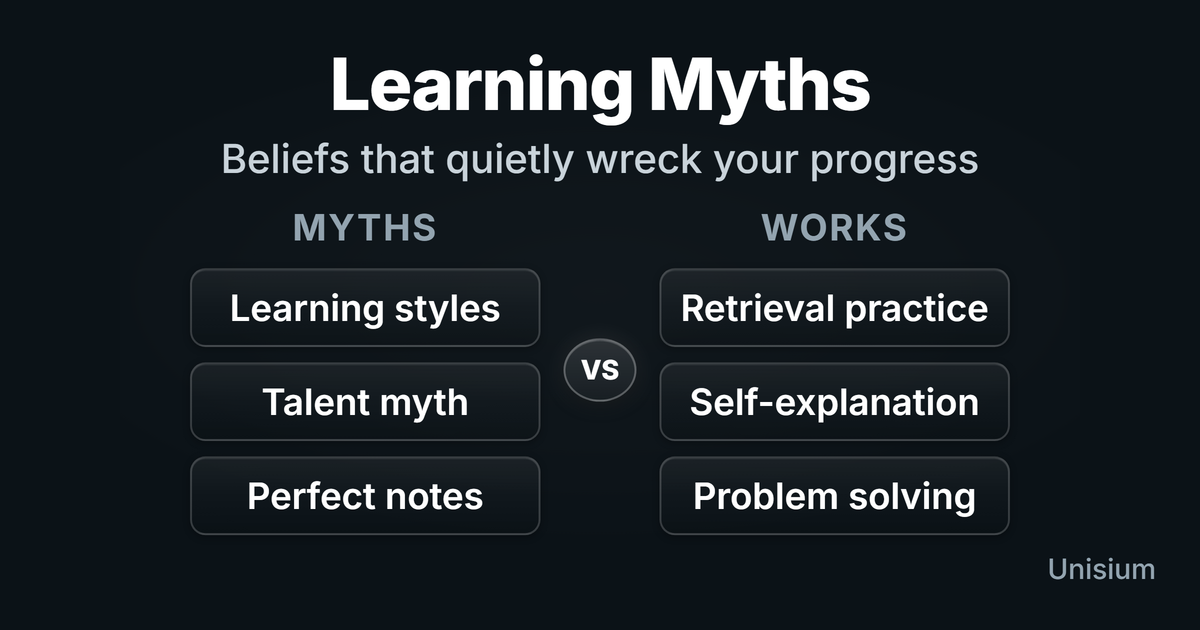

The Big Learning Myths (That Hold You Back in Math and Physics)

A lot of what students “know” about learning is simply wrong. It sounds nice, feels fair, or matches their habits—but it quietly destroys progress in math and physics.

Why bother with myths at all?

Because myths don’t just sit in the background. They drive decisions:

- I’m a visual learner, so derivations aren’t for me.

- Everyone learns differently, so I’ll just do what feels right.

- If the teacher explained it better, I’d get it.

- I’m just not a math person.

- As long as I have good notes, I’m fine.

Each of these pushes you away from the strategies that build skill in math and physics.

This guide is about a few of the worst offenders—and what to do instead.

Myth 1: “I’m a visual / auditory / kinesthetic learner.”

Typical lines:

I’m a visual learner, so I need videos.

I’m a kinesthetic learner, so I can’t learn from textbooks.

The idea: if teaching matches your “learning style” (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, VARK, etc.), you’ll learn much better. It’s tidy, intuitive—and wrong.

What the evidence says

Decades of studies have tried to test this “meshing hypothesis”: people learn better when instruction matches their preferred style. Large reviews keep finding the same thing: matching teaching to self-reported learning styles does not reliably improve learning outcomes, and a 2025 synthesis of meta-analyses found that tailoring to learning styles has an effect size that’s effectively zero—while warning against keeping the myth alive instead of focusing on strategies that work.

Preferences exist. But changing the modality to match your preference doesn’t seem to change how much you learn.

Why it’s especially misleading in math and physics

For university math and physics, most of what you need lives in two modalities:

- Symbolic / verbal – equations, definitions, condition statements.

- Visual / spatial – graphs, free-body diagrams, field lines, geometric pictures.

Good learning here is not about picking one modality and ignoring the other. It’s about moving flexibly between them: turning a word problem into equations and a sketch; translating a graph into a derivative story; or going from a free-body diagram to Newton’s second law and constraints.

Insisting “I’m a visual learner” or “I can’t learn from words” becomes a self-imposed handicap. You’re refusing the exact kind of representation-flexibility experts rely on.

A close cousin of this myth is “writing by hand is better than typing” or “paper beats screens.” Medium can change convenience and how easy it is to get distracted, but by itself it doesn’t create learning. An hour of focused elaborative encoding and retrieval practice on paper beats an hour of distracted scrolling on a phone; an hour of focused work on a screen beats an hour of aesthetic but passive note-copying in a notebook. The problem isn’t “diodes vs ink,” it’s whether your attention is being hijacked or directed into real thinking about the material.

Aside: The Learning Pyramid is made up

You’ve probably seen the “10% of what you read, 90% of what you teach” triangle. The numbers have no solid empirical basis; they’re misattributed to Dale’s Cone and can’t be traced to a real study. Retention depends on timing, difficulty, prior knowledge, and how you’re tested. The useful message isn’t the fake percentages; it’s the same one as the rest of this guide: you remember what you struggle to retrieve and use repeatedly, not what sits neatly in a triangle chart. If you want to use “explain to teach” productively, see the Feynman Technique—it works because it forces self-explanation and retrieval, not because of magic pyramid ratios.

What to do instead

- Use all relevant modalities for the task:

- Forces → diagrams and equations.

- Potentials → graphs and algebra.

- Practice translation, not just consumption:

- Turn text → diagram → equations → verbal summary. - Use concept maps to force labeled relationships between ideas.- Use Elaborative Encoding and Self-Explanation to nail meaning and conditions, not “my style”:

- See: Elaborative Encoding, Self-Explanation.

You don’t have a learning style box. You have a toolbox. Use the whole thing.

Myth 2: “Everyone learns differently.”

On the surface, this sounds kind and humane. It’s also wildly overstated.

Students say:

Everyone learns differently, so I just do what works for me.

That way of studying might work for others, but not for my brain.

Usually this is code for something vaguer: “Some people need lectures, some need to read, some need to solve problems. I just have to find my thing.” Underneath sits the idea that people need fundamentally different processes to learn—lecture vs problem solving vs reading vs videos—rather than different starting points and different amounts of practice.

What the data shows

A massive PNAS study by Koedinger and colleagues modelled over 1.3 million performance observations, across 27 datasets, almost 7,000 learners, and multiple domains (including math and science).

The surprising result:

Students differ a lot in initial performance (how much they know at the start), but when they go through the same learning process on the same skills (practice with feedback, explanatory instruction), their learning rates are astonishingly similar—roughly a 2.5% accuracy gain per opportunity on average.

Reference: Koedinger, K. R., Carvalho, P. F., Liu, R., & McLaughlin, E. A. (2023). An astonishing regularity in student learning rate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 120(13). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2221311120

In other words: people don’t differ that much in how fast they learn given the same sequence of good opportunities. They differ in how much they know at the start and how many quality reps they get on effective processes.

Why this matters for you

If you’re behind in math or physics, it’s usually because you started with less prior knowledge, you’re using weaker strategies, or you get fewer high-quality practice–feedback cycles—not because your brain “needs a different method” than everyone else.

What to do instead

Drop “everyone learns differently” as an excuse and replace it with two more honest lines: everyone learns with difficulty, and everyone needs reps. Skill comes from repeated retrieval, explanation, and problem solving with feedback on the same underlying processes, not from inventing a private learning style.

Then put your effort where it pays off: use Retrieval Practice, Self-Explanation, Problem Solving, plus Spacing and Interleaving, and track how many good passes you’re getting.

You don’t need a different brain. You need more high-quality passes through the right loop.

Myth 3: “If my teacher explained it better, I’d understand.”

Classic lines:

The professor’s bad at explaining.

If someone could just explain eigenvalues right, it would click.

Teaching quality matters, obviously. Terrible explanations waste time. But the idea that the main reason you struggle in math and physics is “bad explanations” is comfortable fiction.

Explanations are input. Learning comes from output.

If polished explanations were enough, you would:

- Watch a brilliant lecture on Gauss’s law.

- Read a clean textbook derivation.

- Walk into the exam and solve novel field problems.

That’s not what happens.

The driver of learning is the work your brain does after you receive explanations: trying to recall the principle without notes, explaining each step of a worked example in your own words, and solving problems where you have to choose the principle and justify conditions.

The opposite mistake is to assume students should discover everything with minimal guidance. Both extremes—pure telling and pure discovery—underestimate how much structured, effortful practice you need.

This is why self-explanation works so well: students who explain steps to themselves build much stronger solution rules than those who just read or listen, even when the initial explanation is identical.

Self-explanation is a process, not a product. The point is not to produce a perfect textbook-style explanation. It’s to grind your way through the logic until it lives in your head.

Why this myth is dangerous

It shifts responsibility away from your process: “I didn’t learn because the explanation wasn’t perfect.” It feeds endless passive input—more videos, more lectures—while you avoid retrieval and problem solving, and it makes you underestimate how many reps each principle needs.

What to do instead

Use explanations as starting points, not end points:

- After an explanation (lecture, video, or book), close the material.

- On a blank page, write:

- Name the principle.

- State its conditions (when it applies).

- Reconstruct the main steps from memory.

- Then do Self-Explanation on one worked example.

- Then attempt at least one fresh problem using that principle.

See:

- Self-Explanation

- Problem Solving

- Five-Step Strategy (for physics)

Explanations are helpful. They are not magic.

Myth 4: “Talent decides who can do math and physics.”

You hear:

I’m not a math person.

She’s just naturally good at physics.

There are real individual differences—IQ, working memory, attention, prior exposure. But the way “talent” is used in everyday student culture is mostly storytelling after the fact.

What “talent” usually hides

When you look closely at the people who seem “effortlessly good” at math or physics, you almost always find years of informal exposure (puzzles, number games, curiosity about how things work), early, dense practice (more reps in school, better feedback, extra problems), and less fear of effort. They don’t treat struggling as evidence of low ability.

And then we call the end result “talent.”

Deliberate practice research is blunt: expert-level performance is built on huge volumes of high-quality practice and feedback, not a tiny spike in “giftedness.” The popular “10,000 hours” idea is oversimplified, but the direction is right: the quantity and quality of effort is the main driver.

Over time, sustained, well-directed work creates what most people point to as “talent.”

The real danger: the “talent curse”

The worst effect of the talent myth isn’t that it flatters high performers. It’s that it locks everyone else down:

- You under-invest in exactly the subjects where you “aren’t talented.”

- You feel ashamed of visible effort—so you avoid the work that would help.

- You abandon topics early instead of grinding through the ugly middle—use a motivation system.

In math and physics, this is fatal. The subjects are cumulative. If you give up on algebra or basic mechanics because they feel “unnatural,” everything built on top collapses. Once fundamentals are stable, don’t just ‘know’—ship outputs with feedback.

What to do instead

Treat “talent” as something you can build: accumulated time, exposure, and high-quality practice that compounds if you start now, not a fixed label you either have or lack.

Build an identity explicitly based on effort and process, not “being the smart one”:

- “I am someone who does the work, even when it’s ugly.”

- “I am building my talent hour by hour.” For practical if-then rules you can run under stress, use effective study mindsets. Focus on the compound growth:

Prior knowledge makes future learning easier, and every principle mastered accelerates the next (mechanics → E&M, calculus → differential equations, data structures → algorithms). The more you know now, the more “talented” you’ll look later.

For a deeper dive, see the “talent” and growth mindset sections in Masterful Learning and connect them to your current course: What would it look like to behave as if talent is created?

Myth 5: “If I take good notes, I’ll be fine.”

This one is everywhere:

I need to fix my note-taking system.

My notes are great—I don’t know why I did badly.

The assumption: if you have beautiful, complete notes and reread them before the exam, learning will take care of itself.

What note-taking trains

In typical lectures—especially derivation-heavy math/physics lectures—note-taking mostly teaches one thing: transcription. Your attention is on capturing what’s on the board, not understanding why it’s there. You practice copying symbols, not selecting principles or checking conditions. Afterwards, you reread the same material. Familiarity rises. Transfer doesn’t.

This is why “good notes” students can still freeze when they see a slightly different exam problem: they never practiced the tasks the exam demands.

See:

Why it’s particularly bad in math and physics

Exams don’t ask:

- “Can you recreate my lecture notes?”

They ask:

- “Can you recognize the structure of this problem?”

- “Can you select the right principle and justify its conditions?”

- “Can you execute the solution without being guided line by line?”

Passive review of notes barely touches those skills.

What to do instead

You don’t need more sophisticated note-taking. You need different work:

- During class:

- Stop full transcription.

- Predict the next step, name the principle, and flag confusion.

- Write questions, not everything said.

- After class:

- Do Self-Explanation on one worked example.

- Solve 1–3 new problems using the Five-Step Strategy (physics) or analogous forward reasoning.

- Run Retrieval Practice on key principles instead of rereading notes.

If you insist on keeping notes, make them a byproduct of thinking (errors, patterns, condition → action → goal rules), not a record of what the lecturer did.

What works (and why it’s the same for almost everyone)

Strip the myths away and the pattern is almost the same for everyone.

For math and physics, almost everyone benefits from the same core loop:

-

Elaborative Encoding

- Build meaning and conditions of use for each principle.

- Use principle tables and structures.

- Guides: Elaborative Encoding, Principle Structures

-

Retrieval Practice

- Recall name → form → conditions → contrast → example without notes.

- Space revisits; interleave neighbor principles.

- Guides: Retrieval Practice, Spacing, Interleaving

-

Self-Explanation

- Walk through worked examples step by step.

- For each step, state: principle, conditions, and what the equation encodes.

- Guide: Self-Explanation

-

Problem Solving

- Attempt fresh problems that force principle selection and justification.

- Use systematic approaches (e.g., Five-Step Strategy in physics).

- Guide: Problem Solving

Structure this with spacing and feedback, and you have a system that works across students, courses, and universities.

A hidden myth: “If it feels easy, it must be working”

Behind many of these myths sits a quieter belief: smooth, easy-feeling study is better study.

In practice, students often rate fluent lectures and passive review as more effective than active methods, even when they learn less from them. In a physics study by Deslauriers and colleagues, students in active classes learned more but felt they learned less than students listening to traditional lectures. Their feeling of learning was flipped compared to their measured learning.

The lesson is blunt: comfort is not a signal of progress. In math and physics, the processes that matter—Elaborative Encoding, Retrieval Practice, Self-Explanation, and Problem Solving—often feel slower and more effortful than rereading or watching solutions. That effort is the mechanism. The goal is not “make it as easy as possible.” The goal is to run the right processes at high quality and give yourself enough spaced, repeated passes through them.

How to use this guide

If you recognize yourself in any of the myths, don’t overthink it. Pick one concrete change:

- Drop “learning styles” from your vocabulary and practice modality translation instead.

- Stop saying “everyone learns differently”—start tracking how many good reps you get.

- After the next explanation you watch, immediately self-explain and solve one problem.

- Start treating “talent” as something you can build now through regular, focused work.

- Replace one hour of note-fiddling this week with Elaborative Encoding + Retrieval Practice on key principles.

Then deliberately build an identity around effortful, high-quality learning processes. The myths are just noise. What moves you forward is what you repeatedly do.

FAQ

Are learning styles real?

Preferences are real, but the “meshing hypothesis” (that you learn better when teaching matches your preferred style) does not hold up well in the research. In math and physics you usually need to translate between words, diagrams, and equations.

What’s the biggest myth that hurts math and physics students?

That input is learning—more videos, more reading, more polished explanations. Skill comes from retrieval, explanation, and solving problems where you must choose a principle and justify conditions.

How do I stop believing myths and start improving?

Pick one process change for the next week: do a short elaborative encoding pass, run retrieval without notes tomorrow, self-explain one worked example, then solve one fresh problem. Repeat and track reps, not feelings.

How This Fits in Unisium

Unisium is built to counter these myths by default: you answer first, you explain your reasoning, and you practice solving, then revisit what matters over time. That’s the Unisium Study System implemented as short sessions with feedback and spacing, so you build competence you can reproduce under exam pressure. Ready to try it? Start learning with Unisium or explore the full framework in Masterful Learning.

← Prev: 6 Ineffective Study Techniques | Next → Retrieval Practice

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →