Problem Solving: The Learning Strategy That Turns Knowledge into Skill

What is problem solving as a learning strategy? Problem solving is learning by doing. It’s the process of turning retrievable knowledge—especially solution rules that link principles to actions—into fluent, automatic skills by using them on real tasks. Instead of treating problems as graded chores, you use them as targeted practice to build skill.

Most students treat problem solving as “the thing after reading” or “the homework I have to submit.” That mindset leaves a lot of learning on the table and often reinforces ineffective study techniques.

This guide draws from Masterful Learning and connects to the physics-focused Five-Step Strategy, which gives a concrete “how” for solving physics problems. Here, we focus on the what, why, and when of problem solving in physics and math.

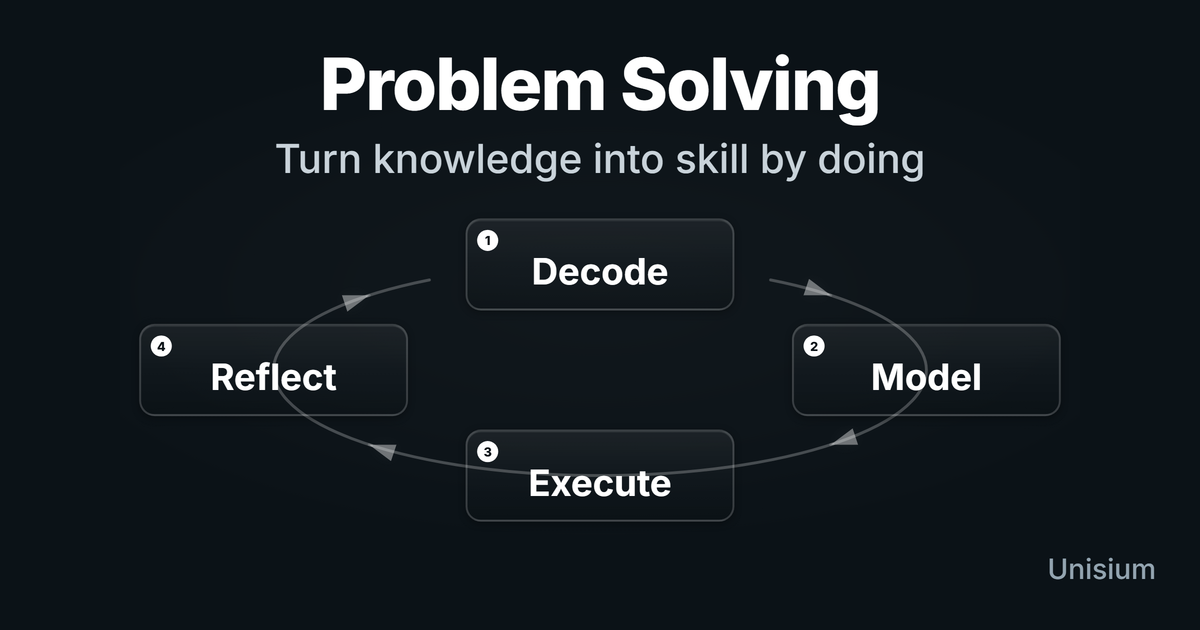

In the Unisium system, problem solving is one of the four primary strategies, alongside elaborative encoding, self-explanation, and retrieval practice. Pretesting, the testing effect, Hint and Try, spacing, and interleaving sit around that core—they don’t replace problem solving, they make it more effective.

On this page: Overview · Why It Works · When to Use · Domain Guidance · Mistakes to Avoid · Pair With Others · FAQ

TL;DR

Problem solving is the strategy that turns retrievable knowledge into skill—especially the solution rules that connect principles to concrete steps. You apply what you’ve learned to real tasks until core moves become automatic and you can handle unfamiliar problems.

Under the hood, your brain leans on four cognitive processes when you’re solving problems: analogy to examples, retrievable solution rules, retrieval of whole solutions or fragments, and unconscious skills.

Homework Mode vs Strategy Mode

| Aspect | Homework Mode | Strategy Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Finish the set, get points | Build skills and test understanding |

| Approach | Copy, hunt formulas, check answers | Forward reasoning with principles, reflection, rule extraction |

| Feedback | Correct/incorrect after the fact | Continuous: “What did I learn from this problem?” |

| Long-term effect | Fragile, context-bound performance | Transferable skills and faster modeling |

What Is Problem Solving as a Learning Strategy?

Problem solving is learning by doing: using principles on real tasks to build skills that become fast and automatic.

When you tackle a problem, your brain can use four cognitive processes to make progress:

1. Analogy to Examples

You copy and adapt a familiar worked example or past solution. It’s the lowest-bar process at low knowledge levels: “this looks like that worked example, I’ll do something similar.” Used on its own, it gives the weakest learning payoff—you get through the problem, but often don’t know why the steps work, and you tend to build shallow, rigid habits rather than flexible understanding.

Students who mainly study by matching problems to worked examples often feel that “the exam was totally different from what we practiced,” even when the underlying solution structures are almost identical. What changed was the surface story, so their pattern matcher failed. When your skills live at the level of principles and condition–action–goal rules, those same exams feel “fair but demanding” instead of “completely new.”

To get real value from analogy, you need to pair it with self-explanation. After you adapt an example, ask: What principle was used here? Under which conditions? What was the goal of this step? That turns copied moves into retrievable solution rules, not just muscle memory.

2. Retrievable Solution Rules

These are explicit, verbalizable “if–conditions–then–actions–for–this–goal” rules, e.g.:

If only gravity does work on the object and I care about speed and height, then I can use mechanical energy conservation to relate them.

You usually build these rules through self-explanation (of your own solutions or worked examples). A good rule makes four things explicit:

- Principle — what core idea is being used?

- Conditions — when does it apply (and when not)?

- Action — what do you do on the page?

- Goal — what is this step trying to achieve?

Self-explanation is mostly about dragging those four elements into the open and putting them in your own words. Over time, you accumulate a library of rules you can deliberately retrieve and adapt.

For learning and long-term expertise, this is where much of the payoff sits:

- Retrievable rules are flexible: you can reshape them for new problems.

- They give you a handle on your own skills: you can debug, refine, and combine them.

- They underpin transfer: when a problem changes, you can still reason your way through.

They are mentally expensive: you have to notice that a rule might apply, pull it into working memory, and adapt it to the specific structure and numbers in front of you. That effort is not a flaw—it’s the work of real understanding. Early on, rule-based thinking feels slower than relying on habits or copying examples, but it’s exactly this deliberate, rule-level processing that lets you handle unfamiliar problems later. Unconscious skills give you speed; retrievable solution rules give you flexibility. You need both.

What You’re Trying to Build

In Unisium terms, the “unit” you want to get out of problem solving and self-explanation is a small condition–action–goal pattern tied to a principle:

- Condition: what you see in the problem (situation, diagram, given information).

- Action: what you do (set up an equation, isolate a variable, choose a substitution).

- Goal: what this move is trying to achieve (simplify, relate two quantities, prepare for a conservation law).

- Principle: the core idea that justifies the move.

A good rule might sound like:

If my goal is to relate height and speed, and only gravity does work on the object, then I can apply mechanical energy conservation to connect them.

Self-explanation makes these explicit and verbalizable.

Problem solving tests, refines, and eventually automates them. Over time, many of these condition–action–goal patterns get compiled into unconscious skills—so they fire automatically when the right conditions and goals are present.

3. Retrieval of Whole Solutions or Fragments

Sometimes you don’t just recall a rule—you recall an entire solution (or a big chunk of it):

- You see a highly familiar incline problem and your brain replays the whole chain of steps you’ve used before.

- You remember that a particular algebra manipulation or move worked in a nearly identical situation and you reproduce it.

For basic facts and small chunks of procedure, this process is exactly what you want:

- Low-number addition and multiplication (e.g., 6 × 8 = 48) are most efficient when they’re simply retrieved.

- In more advanced physics and math, standard sub-routines—like “resolve forces on an incline,” “complete the square,” or “differentiate a simple power function”—eventually become ready-made solution patterns you can replay almost instantly.

This saves time and effort on routine tasks and frees up working memory for modeling and decisions. But it has clear limits:

- It only works well when the new problem is closely related to an old one.

- It breaks down on exam twists or novel problems where your old solution doesn’t quite fit.

For real transfer, you still need good solution rules underneath; otherwise full-solution recall is brittle. The rules tell you when and why a remembered solution pattern applies—and when you need to adapt or abandon it.

4. Unconscious Skills

These are compiled, automatic skills: fast links between cues and actions that no longer require much conscious reasoning.

Examples:

- If all terms have the same mass, cancel the mass.

- If an expression has the same factor in every term, factor it out.

- If momentum is conserved, the system must be isolated.

On paper, those look like retrievable rules. In real problem solving, they run differently:

- You notice that all terms have the same mass and your current goal is to simplify → you automatically cancel it.

- You see a common factor in every term and your goal is to clean up the expression → you just factor it out.

- You recognize an isolated system and you’re trying to relate before/after motion → you immediately treat momentum as conserved.

In practice it’s cue + active goal → action. The goal is often implicit (“simplify,” “solve for v”), but it still decides when the habit fires. There’s no slow “let me recall the rule” step—that’s what distinguishes unconscious skills from retrievable rules.

Unconscious skills are largely the fruit of repeated problem solving:

- You start with explicit solution rules you can say out loud.

- With spaced repetition across many problems, your brain compiles them.

- Cue + goal → action becomes fast and cheap, freeing up working memory for modeling and multi-step reasoning.

The catch: unconscious skills are efficient but rigid. If they’re built on shallow, copy-the-example thinking (or vague goals like “just get rid of stuff”), you get fast but wrong responses in new situations. Also, you can’t skip directly to unconscious skills—you earn them by doing many repetitions.

Why Problem Solving Builds Skill

The purpose of problem solving is to convert retrievable knowledge—especially solution rules—into unconscious skills you can use under pressure.

1. It automates core moves and frees working memory

At first, solving a problem is slow and effortful:

What principle applies? What comes next? How do I rearrange this?

That deliberate recall is necessary in the beginning, but it’s not where you want to stay. With repeated, well-structured problem solving:

- You start to recognize situations instead of rebuilding them from scratch.

- You apply the right method without pausing to think about every micro-step.

- Routine algebra and standard patterns become fluent and low-cost.

That’s automation. And once basic moves are automated, you can spend your mental resources on higher-level tasks: choosing models, interpreting results, checking edge cases, and handling twists, instead of fighting the algebra on every line.

2. It strengthens memory for solution rules

Problem solving doesn’t just use your knowledge—it strengthens it.

Every time you recall and apply a solution rule, you:

- Practice retrieving the rule in a realistic context.

- Clarify its conditions of application.

- Tie it to a specific goal and set of actions.

That combination—retrieval in context plus action—is what makes a rule easier to access next time and more stable over the long term. It’s the double payoff: you reinforce the memory and improve your fluency with it at the same time.

3. It exposes knowledge gaps instead of vague “I’m bad at this”

A problem forces you to commit. When something breaks, you can usually trace it to one of three things:

- Recall — you couldn’t bring a principle, formula, or rule to mind.

- Condition — you chose the wrong tool or misread the situation.

- Procedure — you chose a reasonable idea, but got lost in the steps.

That kind of failure is useful: it tells you exactly what to fix next. Vague reading discomfort (“this chapter feels hard”) doesn’t give you that. Systematic problem solving turns “I’m bad at physics/math” into targeted next actions: retrieval drills, clarifying conditions, or self-explaining solution steps.

4. It builds transfer, not just pattern matching

Students who mostly copy examples or hunt for look-alike problems often feel betrayed by exams:

The exam was totally different from the practice problems.

In reality, the surface story changed while the solution structure stayed the same. Example-matching skills don’t survive that shift.

When you solve problems by working at the level of principles and condition–action–goal rules, what you practice is:

- Recognizing structures across different surface stories.

- Choosing principles based on conditions, not keywords.

- Adapting familiar moves to new numbers, contexts, and diagrams.

5. It biases your brain toward the right default processes

Your brain tends to fall back on whatever is:

- Most available — what you’ve retrieved and used often, and

- Least effortful — habits and examples before explicit rules.

If your study life is mostly watching solutions and lightly adapting examples, you train your brain to rely on analogy + shallow habits. It feels efficient until the problems change.

If, instead, you solve problems, retrieve principles, and self-explain your own and others’ solutions, you gradually make:

- Strong solution rules and

- High-quality unconscious skills

the easiest options to fall back on.

That’s the real reason problem solving builds skill: it changes what your brain treats as the default way to make progress on a problem, from “find something that looks similar” to “use a rule I understand and can adapt.”

Domain-Specific Guidance

Physics: From Formula Hunting to Modeling

- Aim to categorize problems by principles (Newton’s laws, energy, momentum, rotation), not by surface features (“elevator problem,” “spring problem”). See Names Have Power for why this labeling shift matters.

- Use diagrams and free-body diagrams as thinking tools, not decoration.

- For the “how,” lean on the Five-Step Strategy: verbal decoding → visual decoding → physics modeling → math → reflection. In other words: model first, calculate second.

Many students initially “just try to finish problems” by pushing symbols around until something works. In our physics courses, we’ve seen that once students are exposed to physics modeling—separating verbal decoding, diagrams, principle choice (with conditions), and math—they gradually adopt it because it works better. It feels slower at first, but over time it beats formula hunting on anything beyond the simplest exercises.

Mathematics: From Tricks to Structure

- Focus on the structure: symmetry, continuity, linearity, constraints, limiting behavior.

- Distinguish between modeling problems (turn words into math) and transformational problems (simplify or manipulate given expressions).

- Reflection often means checking limiting cases, graphing, or comparing multiple solution paths.

Note: The same logic—decode the situation, model with principles, execute, and reflect—applies to problem solving in programming and other technical domains. Unisium currently focuses on physics and math, but the learning structure carries over.

When to Use Problem Solving

After You Have Some Grasp of the Principles

Trying to learn a brand-new topic purely by brute-forcing problems is usually a bad deal. If you can’t yet state the core principles and their conditions of application, you mostly end up guessing, copying, or memorizing surface patterns.

Early on, it’s better to lean on elaborative encoding, retrieval practice, and self-explanation. Once you can retrieve the basics reasonably well, then it makes sense to shift more of your time into problem solving. This is the expertise-reversal effect in action: the more knowledge you bring to the table, the more problem solving pays off.

A simple session pattern once you’re ready could look like this:

- Do a brief retrieval warmup (5–10 minutes) on key principles and formulas.

- Work through 1–3 moderately hard problems that force you to think.

- Spend 1–2 minutes reflecting on what you did and extract at least one solution rule or pattern.

- When you get stuck, self-explain the solution instead of just copying it; use that to fill specific gaps.

The important part is that each session both tests your current rules and adds new or sharpened condition–action–goal patterns tied to principles.

As a Diagnostic at the Start of a Session

Problem solving is also a good diagnostic tool. Starting a session with one or two problems quickly tells you where you stand.

If a problem feels trivial, you level up. If it’s challenging but doable, you’re in the right zone. If it feels impossible and you’re flailing, that’s a signal to step back to examples, hints, or prerequisite principles. Let the problems steer your study plan instead of just filling time.

When you review a miss, classify it mentally:

Recall: you couldn’t bring a principle, formula, or solution rule to mind at the right moment.

Condition: you knew the tool, but used it in the wrong context or missed a key assumption.

Procedure: you chose a reasonable idea, but got lost in algebra, proof steps, or other manipulations.

Regardless of the classification, the first follow-up move is self-explanation of the solution (ideally to the same problem, or to a closely related one if needed):

For Recall issues, self-explain with a spotlight on which principle or rule is used and why it fits this situation. If it still won’t stick afterwards, then add targeted retrieval practice on that principle or rule.

For Condition issues, self-explain how the conditions of application show up (or fail) in the problem. If those conditions feel vague or ad hoc, that’s your cue to go back to elaborative encoding and principle structures to sharpen when the principle applies.

For Procedure issues, self-explain the transformations themselves—each algebraic step, proof move, or manipulation and what its immediate goal is. Then reinforce with more problem solving that uses the same kind of transformation.

Spaced Over Time, Not Crammed

Problem solving works much better spread out than crammed into a single long session. A string of short, focused sessions gives you more retrieval, more forgetting-and-recalling cycles, and more chances to vary the context.

In practice, that means sprinkling problems across days and weeks instead of saving everything for the exam period. Within a single session, mix different types of problems so you have to decide what kind of problem this is and which principle applies. That choice between problem types is the core of interleaving.

Pair your problem sets with short retrieval practice bursts as session kickstarts so you also benefit from the testing effect and spacing effect on principles. You want your principles and solution rules to be both well-practiced and regularly pulled from memory, not just re-seen.

When You Can Turn Knowledge into Automation

Problem solving gives you the biggest return when you already have some retrievable rules and the problems reuse sub-skills you can automate. If you know what you’re trying to do—set up conservation of energy, isolate a variable, choose a standard differentiation pattern—then each problem reinforces that rule and pushes it toward automation.

Typical examples are algebra manipulations, standard patterns in calculus, or common physics setups (inclines, circular motion, simple energy exchanges). In those cases, problem solving both strengthens the underlying rule and chips away at the cognitive cost of executing it. Over time, those condition–action–goal patterns move from deliberate retrieval toward unconscious skill.

If, on the other hand, every step feels like guessing or random symbol pushing, that’s a sign you need to go back and build or clarify the rules first—again, usually through self-explanation plus targeted retrieval and elaborative work.

Research Spotlight: What Predicts Better Problem Solving?

In studies I’ve done with introductory physics students, we collected hundreds of written self-explanations of worked examples and then looked at who improved most on later problem-solving tests. Two patterns showed up.

First, students who explained which principle was used, how it was set up, and why its conditions were met performed better on new problems later. Second, when students retrieved key principles and their conditions before studying examples, their explanations became higher quality and their later problem-solving scores improved.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Staring at problems you can’t solve or copying solutions and calling it “practice.”

- Fix: Struggle first. If stuck, reveal one step, then close the solution and continue. Afterwards, self-explain the full solution.

Grinding only easy problems.

- Fix: Keep some easy warm-ups, but deliberately add problems that force you to think, not just execute.

Chasing answers instead of rules.

- Fix: After each problem, ask: “What rule or pattern did I strengthen here?”

Skipping reflection.

- Fix: Even 1–2 minutes of sanity checks and rule extraction pays off significantly.

Not classifying mistakes.

- Fix: When you review mistakes, don’t just say “I messed up”—classify them as Recall / Condition / Procedure. Fix recall with retrieval practice, conditions with elaborative encoding and principle structures, procedures with self-explanation on worked examples.

Pair It With Other Strategies

Problem solving isn’t the whole game. It works best inside a system:

- Elaborative Encoding — Build meaningful connections around principles.

- Retrieval Practice — Make principles easily accessible.

- Self-Explanation — Turn worked examples into explicit solution rules.

- Problem Solving (this guide) — Apply principles in problems to build skill and automation.

Encoding builds the content of your knowledge.

Retrieval keeps it alive.

Self-explanation builds know-how.

Problem solving trains it into usable skill.

All four primary strategies are working on the same thing from different angles: condition–action–goal patterns tied to principles. Self-explanation and elaborative encoding help you form them, retrieval practice keeps them accessible, and problem solving tests and compiles them into reliable skill.

For a concrete weekly plan that weaves these four strategies into your self-study time, see How to Self-Study Math and Physics Effectively.

FAQ: Common Questions About Problem Solving as a Learning Strategy

What is problem solving as a learning strategy?

It’s using problems deliberately to convert retrievable knowledge—especially solution rules that tie principles to actions—into skill. You choose problems and approaches designed to strengthen modeling, reasoning, and automation—not just to get homework done.

What’s the difference between forward and backward strategies?

- Backward: Start from the desired answer and hunt for formulas, tricks, or snippets that produce it.

- Forward: Start from what’s given, identify applicable principles, and build a model or plan.

Forward strategies are slower initially but build deeper understanding and transfer.

How many problems should I solve?

There’s no magic number. A small number of well-solved, reflected-on problems beats a huge set of rushed ones. For many sessions, 3–6 carefully chosen problems is plenty, especially if you self-explain one or two.

When is problem solving not the best tool?

- Early in a topic, when you can’t even state the principles.

- When you’re so lost that you’re just guessing or copying.

In those cases, lean on examples, elaborative encoding, and self-explanation first.

Is it okay to look at solutions?

Yes—if you do it deliberately. Use solutions as scaffolds, not shortcuts:

- Try first.

- If stuck, reveal a partial solution step.

- After seeing the full solution, self-explain it and extract rules.

- Later, reattempt the problem (or a variant) without help.

From “I’ve Seen This” to “I Can Do This”

Solving problems isn’t just about “getting the right answer.”

What passive reading gives you: familiarity with ideas.

What problem solving gives you (done right): the ability to recognize structures, choose principles, and execute solutions under pressure.

That’s the gap between “I’ve seen this” and “I can do this.” Problem solving is where you take principles, examples, and solution rules and beat them into condition–action–goal patterns you can rely on in new situations.

Related Learning Guides

Five-Step Strategy for Problem Solving — The concrete, physics-focused method for structuring your problem solving.

Self-Explanation: Learning from Worked Solutions — Turn examples and solutions into reusable rules.

Retrieval Practice: Make Knowledge Stick — Keep principles accessible so you can use them in problem solving.

Elaborative Encoding: Learn Faster with Better Connections — Build the meaningful connections that make problem solving possible.

Get the Complete System

This guide draws from Masterful Learning, which offers a full framework for combining elaborative encoding, retrieval practice, self-explanation, and problem solving into a coherent study system for physics and math (with extensions to programming).

How This Fits in Unisium

Unisium is a learning app for physics and math that bakes systematic problem solving into the study flow. The Unisium Study System uses problem-solving cards that track whether you solve problems without seeing full solutions, offering AI feedback on your problem solving steps and strategy.

Problem solving is domain-general. The structure—decode the situation, model with principles, execute the plan, reflect on what worked—translates across physics, mathematics, programming, and beyond. What changes is the vocabulary and the specific principles you draw on, not the learning process itself.

← Prev: Self-Explanation | Next → Retrieval Practice

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →