Self-Explanation: Learning from Worked Solutions

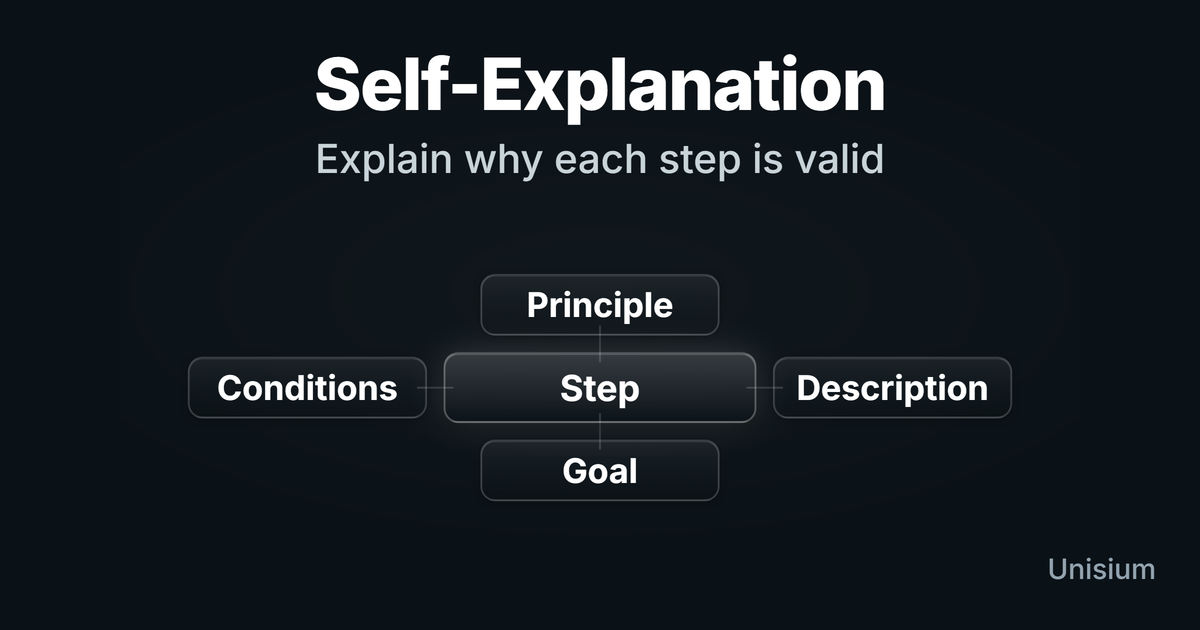

Self-explanation is learning from worked solutions by explaining why each step is valid: which principle is used, which conditions make it apply, and what the step achieves. It works because it turns a fluent-looking solution into retrievable “condition → action → goal” rules you can reuse on new problems. Use it whenever you can follow an example but can’t reproduce the reasoning on a blank page.

Self-explanation is the process of explaining the reasoning behind each step in a worked example — to yourself or to someone else — with the goal of understanding what’s being done, why it’s being done, and when it’s appropriate.

In physics, this is one of the fastest ways to turn examples into reliable problem-solving skill.

Done well, it produces retrievable solution rules: structured, memory-friendly rules you can recall and adapt in new problems.

Drawn from the self-explanation framework in Masterful Learning, which includes examples, practice exercises, and integration with other learning strategies.

Self-explanation as a learning strategy is a process, not a product. Don’t worry about crafting the perfect explanation right away. What matters most is that you actively wrestle with the material yourself. Studies consistently show that the act of trying to explain something — even imperfectly — creates stronger learning than passively absorbing someone else’s polished explanation. This is the antidote to one of the biggest myths about learning: the belief that received explanations, not your own effort, create understanding. Your ability to explain will naturally improve through practice, not by waiting until you think you’re ready to give a flawless account.

Why Self-Explanation Works

When you self-explain, you:

- Expose gaps – You spot where your understanding is incomplete.

- Anchor principles – You link each step to the conditions and concepts that justify it.

- Build retrievable solution rules – Each explained step becomes a structured memory: condition → action → goal. (Strengthened later through retrieval practice.)

- Strengthen transfer – You learn to see past surface details and map problems to the underlying principles.

Self-Explanation vs. Weak Explanation

Weak explanations just narrate actions:

First, set this equal to that. Then plug in the numbers.

Strong explanations reveal the logic:

We apply conservation of mechanical energy because only gravity does work. The system starts with potential energy and ends with kinetic energy.

The difference?

Weak = procedures without purpose.

Strong = principle-driven rules you can reuse.

How to Self-Explain in Physics

Physics solutions almost always have two parts:

- The Physics Model – Selecting and expressing the relevant principles as equations.

- The Mathematical Procedures – Manipulating those equations to find the target variables.

The model is where most learning happens.

Your self-explanation should cover four elements for each equation in the model:

- Principle – Name it (Newton’s 2nd law, conservation of momentum, etc.). (See Principle Structures for organization, and Names Have Power for why correct naming drives understanding.)

- Conditions – Why it applies here. What in the problem justifies it?

- Description – What each term means, why signs or trig functions are chosen, and how the equation links to diagrams.

- Goal – How this equation moves you toward the target variables.

For mathematical procedures, use the Condition–Action–Goal lens:

- Condition – Why this operation is valid.

- Action – What you did (e.g., “divide through by mass”).

- Goal – Why you did it (“to isolate acceleration”).

Example: Complete Physics Model Explanation

Let’s see how to fully explain the physics model from our ninja problem. This demonstrates the depth of explanation that transforms examples into expertise.

Mathematical Physics Model

Energy on the ramp (ninja only):

Impact with the sack (instant after collision, horizontal direction):

Start of the swing (bottom of the arc, radial upward):

Principle

Conservation of Mechanical Energy (ramp): With no friction, gravity converts potential energy into kinetic energy. Total mechanical energy of the ninja is conserved while sliding.

Conservation of Linear Momentum (collision): The grab is a short, inelastic collision. External horizontal impulse on the ninja+sack system is negligible; vertical impulses (rope tension, weight) act perpendicular to the incoming motion. So horizontal momentum is conserved during the impact (energy is not).

Newton’s Second Law (swing): At the bottom of the swing, the rope must provide the centripetal force in addition to supporting weight. Apply Newton’s 2nd law in the radial direction.

Conditions

Energy step: Ramp is frictionless; air drag neglected; height drop ; speed at ramp bottom () is tangent to the ramp and effectively horizontal at the exit. All work done on the ninja comes from conservative forces (gravity), satisfying the condition for conservation of mechanical energy.

Collision step: Contact time is brief; sack initially at rest; treat the grab as perfectly inelastic (they move together with speed right after). The sum of external forces on the ninja+sack system is zero in the x-direction, and internal forces between ninja and sack cancel due to Newton’s third law, satisfying the condition for conservation of linear momentum.

Swing step: Immediately after the collision they are at the lowest point of a circle of radius ; speed is ; forces along (toward the pivot) are upward and downward. The acceleration is purely centripetal (directed toward the center), satisfying the condition for applying Newton’s second law in circular motion.

Relevance

We need tension right after impact. That depends on the instantaneous speed at the bottom of the arc.

To get , we first get from energy on the ramp, then use horizontal momentum in the inelastic collision.

With known, radial Newton’s 2nd law at the bottom gives directly.

This route is minimal: energy → momentum → radial force. Any alternative (e.g., time-resolved dynamics on the ramp or during the grab) adds complexity without changing the needed quantities.

Description (what each equation encodes)

Left: initial kinetic from the run () plus gravitational drop .

Right: kinetic at the bottom of the ramp. Mass cancels; friction does not sap energy.

Before: only the ninja carries horizontal momentum .

After: ninja + sack move together at (perfectly inelastic).

Energy loss to deformation/heat is expected; we don’t equate kinetic energies.

Upward tension minus weight supplies the required centripetal force toward the pivot.

Rearranged: . Weight term + centripetal term.

Goal

Solve in the sequence the model dictates:

Plug numbers to obtain (≈ with the provided data).

Deepen Your Understanding

Now that you’ve self-explained this solution, the next step is to lock the equations and decision rules in memory through retrieval practice. Extract the key principles from this solution and test your recall of them regularly over the coming weeks.

← Prev: Elaborative Encoding | Next → Five-Step Strategy

Practical Tips

- Focus on principles first – Tying each step to the right principle greatly increases retention.

- Ask specific questions – “Why sine and not cosine?” “Why is normal force downward here?”

- Explain back – If someone (or an AI) explains a solution, restate it in your own words.

- Use drawings – Link equations to free-body diagrams or sketches.

- Mentally explain – Full written explanations are slow; mental ones keep momentum for most study sessions.

- Space it out – Revisit the same solution after a day or more; your recall will be tested and reinforced.

When to Self-Explain

- When you can’t solve a problem – Don’t grind endlessly; switch to learning mode.

- When starting new material – Early problems are for learning patterns, not just solving.

- When using help or copying code – You don’t “own” the solution until you can explain it.

- When examples appear in textbooks – They’re goldmines; mine them fully.

- Until rules become automatic – Once you can instantly recall and apply them, you can phase out full self-explanations for that topic.

If you need guidance while you self-explain, Hint and Try shows how to peek at only the tiniest hint, respond with your own step, and come back for spaced retries. Pairing that with targeted AI prompts (see How to Study Physics and Math with AI) keeps the machine on the hook as a tutor, not a solver.

Continue Learning

Become an excellent problem solver: Our guide on the Five-Step Strategy shows you how to solve physics problems systematically.

Get a weekly plan: For a bigger-picture view of how self-explanation works together with retrieval practice, elaborative encoding, and problem solving across a full week, see How to Self-Study Math and Physics Effectively.

Go deeper: For comprehensive coverage of self-explanation and other research-backed learning strategies, check out Masterful Learning — a complete framework for developing expertise in any technical domain.

Why This Matters

Self-explanation is more than a study technique:

- It builds the principle-based problem categorization experts use.

- It produces a mental library of patterns, like a chess grandmaster’s.

- It transfers to the workplace — helping you learn tools, codebases, or workflows faster.

In short:

If you want to get better at solving physics problems, self-explain worked examples until the reasoning is second nature.

FAQ

What is self-explanation?

It’s the habit of explaining each solution step in terms of principle, conditions, and goal—so you learn the decision rules, not just the algebra.

How long should self-explanation take?

Usually 5–15 minutes for one worked example. Keep it tight: one sentence per step is often enough if it names the principle and condition.

What should I do if I can’t explain a step?

Pause and backfill: restate the goal of the step, identify the principle it relies on, and check the conditions. If you still can’t justify it, that’s a targeted gap for elaborative encoding or a quick reference check.

How This Fits in Unisium

Unisium is a learning app for physics and math that bakes self-explanation into the study flow. The Unisium Study System uses worked-example cards that prompt you to explain each step’s principle, condition, and goal, turning passive reading into active rule-building with AI support to critique your explanations.

Self-explanation is domain-general. Self-explanation is learning from worked examples by making the hidden reasoning explicit. You narrate why each step is allowed, what condition triggers it, and how it moves you toward the goal. Short is fine; precision beats prose. It’s distinct from elaboration about “related ideas”—this is about the logic of the solution path. Whether you’re studying a chess match, reviewing open-source code, analyzing a legal precedent, or watching a master solve a problem in your field, self-explanation extracts the decision rules that experts use.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →