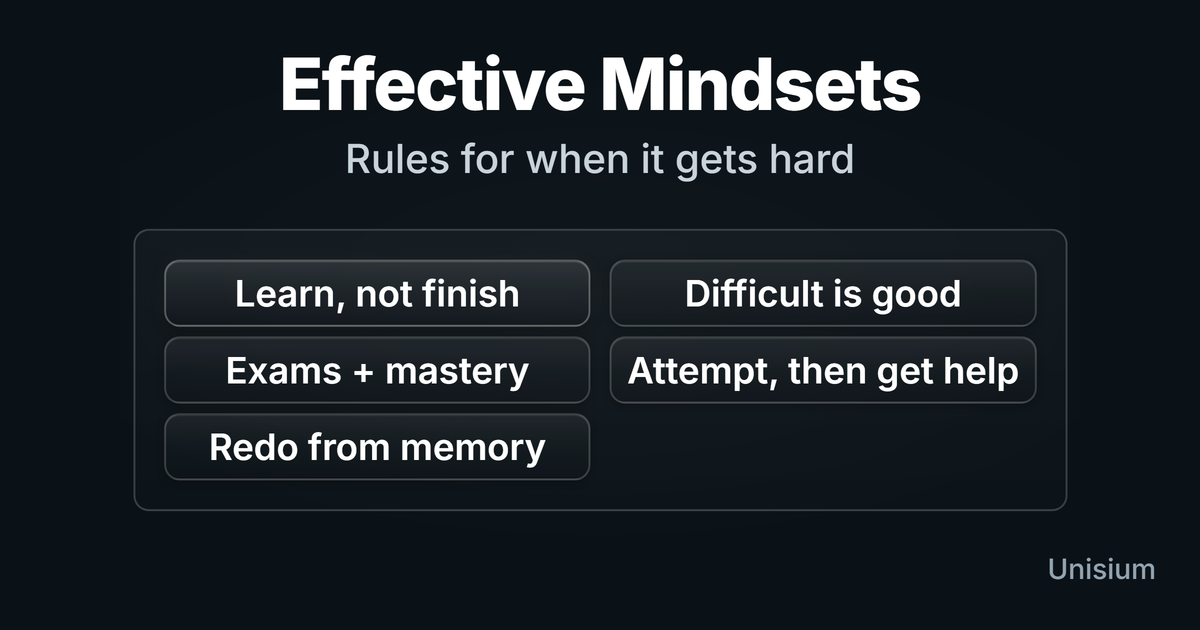

Effective Study Mindsets for Math and Physics Mastery

Effective study mindsets are ways of framing your situation and default rules for what you do next when math or physics gets hard. They steer your week (macro) and show up at decision points (micro). Use them to keep attempting, checking, and redoing from memory even when motivation is low.

On this page: Why It Works · Macro vs Micro · Mindsets That Win · How to Build a Mindset · Signs You Slipped · FAQ · How This Fits in Unisium

Why It Works

Math and physics are high-friction domains. You will hit confusion, slow progress, wrong answers, and moments where you’d rather do anything else. A mindset is the rule you use to interpret that friction — and the interpretation determines your next action.

In practice, mindsets win by changing behavior under pressure: attempt → check → redo from memory instead of avoidance, comfort-work, or searching for relief. If you want these rules to show up reliably, you need cues — see Study Habits.

A productive mindset pushes you toward strategies that force reconstruction and feedback: retrieval practice, self-explanation, and structured problem-solving. These aren’t willpower tricks. They work because they create signal: you try, you find what’s wrong, and you fix it.

The deeper version of this idea is in Masterful Learning: beliefs don’t matter because they’re true; they matter because they steer attention and behavior when it’s inconvenient.

Skeptical take: Motivation is unreliable. Mindsets and habits matter most when motivation is low. If you’re interested in how to keep motivation higher and start more easily, see How to Stay Motivated Studying Math and Physics.

Personal note: I used to protect an identity of being “smart” and not needing to work hard. From around eighth grade my results slid, and by the end of high school I had mostly low grades and even failed the final math exam. I retook courses later, started university at 22, and the pattern flipped: sustained effort plus feedback loops produced excellent grades. That’s why I treat effort as a trained behavior, not a fixed identity.

Want the complete framework behind this guide? Read Masterful Learning.

Macro vs Micro

A mindset isn’t a pep talk. It’s a policy you run over weeks.

- Macro: what you optimize for repeatedly (mastery vs completion, signal vs comfort, growth vs ego-protection).

- Micro: what you do at key decision points (stuck, tired, embarrassed, behind).

If it doesn’t steer your week, it’s not a mindset. If it doesn’t change what you do next, it isn’t installed.

Mindsets That Win in Math and Physics

These aren’t slogans. They’re the rules that keep skill compounding while others stall.

1) Learn, not finish

Most students optimize for relief: “get it done.” Winners optimize for understanding. Over a semester, that one choice compounds.

When it gets hard: you slow down and ask, “What am I supposed to understand here?” not “How fast can I escape this?“

2) Difficult is good

Difficulty is not a verdict. It’s usually a sign you’ve reached the edge where learning happens. If you can learn to lean into the hard parts, you get a real edge — because most people avoid them.

When it gets hard: you treat the difficult part as the main event, not a reason to bail.

3) Effective studying is worth a lot per hour (hours compound)

Most students treat study time like a cost: something to minimize. That’s backwards. In math and physics, focused hours are one of the highest-return investments you can make because skill compounds — what you learn this week makes next week easier.

Over the long run, this shows up as more opportunities and less risk: better exam performance, more confidence taking hard classes, and a higher ceiling for internships, research, and earnings.

When it gets hard: you stop asking “How little can I do?” and ask “What skill am I buying with this hour?“

4) Exams and mastery together

Exam focus without mastery produces brittle performance. Mastery without exam realism can waste time. You want both: exams shape what to practice; mastery shapes how deeply you understand.

When it gets hard: you practice the format you’ll be tested on — and you refuse to accept shallow understanding.

5) Help people who want help (and learn from it)

Helping classmates who are trying is one of the fastest ways to deepen your own understanding. It forces retrieval, explanation, and flexibility — and it turns you into the kind of student others route through.

When it gets hard: you say yes when you can — with a boundary: they show an attempt, and they do the writing.

Two micro-rules:

Attempt, then get help (no negotiation: try first, then seek support)

Redo from memory (after help, redo the core step without looking)

How to Build a Mindset (EE → RP → SE → PS)

Don’t try to adopt five mindsets at once. Pick one. Build it like you build knowledge: elaborate, retrieve, explain examples, then live it until it becomes a habit.

Step 1 — EE: Name it, then elaborate it (why / when / future)

Start with a short name you can remember.

Examples:

- Learn, not finish

- Difficult is good

- Hours compound

- Exams + mastery

- Help people who want help

Then write 6–10 lines using this template:

- Why (goals): Why does this matter for me this semester — and who does it let me become?

- When (cue + failure mode): What situations usually trigger my old pattern (avoidance, comfort-work, ego)?

- Future (results + emotion): What will be true in 30 days, 3 months, 3 years, and 30 years if I run this? How will that feel?

This is the mindset “meaning layer.” If it isn’t personal, it won’t survive pressure.

Step 2 — RP: Retrieve the mindset principle on a schedule

What you want to retrieve isn’t just the name. It’s the mini-principle:

Name → When → Why → What I do next

Create a simple retrieval prompt. For example:

- Front: “Difficult is good — when does this apply?”

Back (what you must retrieve): your cues + your next action + your reason.

Ways to cue retrieval:

- Anki / flashcards: one card per mindset

- Index card in your notebook: read the name, then recall the rest

- Calendar reminders: once per week (or before your hardest study block)

The point is not “remembering a quote.” It’s repeatedly reconstructing why / when / future, so the mindset becomes available on bad days.

Step 3 — SE: Explain real examples of the mindset in action

Self-explanation is not “describe the mindset again.” It’s explaining cases until you recognize the mindset in the wild.

Pick 3–5 examples (best: your own). If you don’t have any, use “near-future you” scenarios that are realistic.

Use this template:

- Situation: What happened?

- Mindset: Which mindset applies?

- Conditions: Why does it matter here?

- Actions: What does someone with this mindset do next, concretely?

- Purpose: What goal does the action protect (mastery, progress, long-term compounding)?

This builds recognition — and it uses the self-reference effect when the examples are yours.

Step 4 — PS: Practice it at the moment you normally break

A mindset becomes real when it changes behavior inside friction.

Pick 1–2 “moment of truth” triggers:

- wrong answer again

- stuck early

- embarrassed to ask

- behind and panicking

Then make the action small and automatic. A good universal micro-routine is:

Attempt → check → redo from memory.

Because it forces an honest attempt, a check, and a correction.

Step 5 — Weekly review: update your cues, don’t moralize

Once per week (2 minutes), answer:

- Where did I run the mindset?

- Where did I slip — and what triggered it?

- What cue or action would make this easier next week?

You’re not judging character. You’re tuning a system.

Signs You Slipped (and What to Do Next)

These aren’t moral failures. They’re indicators that an older rule took over (avoidance, ego-protection, passive comfort). The fix is to change the situation or constraint — not to “try harder.”

| Sign | What to do next |

|---|---|

| You’re doing tasks to be done, not to learn | Write one learning target for the session (one sentence). If you can’t write it, your task is too vague. |

| You avoid the difficult parts and “warm up” forever | Start with 10 minutes on the hardest bottleneck. Warm-ups are allowed after you’ve touched the edge. |

| You seek hints early (relief-seeking) | Set a “no-help window”: attempt for 8 minutes first. Then get help. Then redo one key step from memory. |

| You’re spending time but not improving | Switch mode: stop consuming and produce something checkable (a derivation attempt, a solution sketch, a 60-second explanation). |

| You’re behind and panicking | Shrink the task to a single concrete attempt (one problem, one derivation, one concept), then build outward. Panic is a bad planner. |

| You isolate and only ask for help when desperate | Join one study arena (group, workshop, office hours). Or help one person who’s trying. Social structure is a performance enhancer. |

| You protect an image (“I shouldn’t need this”) | Make the goal “corrections made,” not “looking smart.” Do one hard rep privately. Log the correction. Move on. |

FAQ

What are effective mindsets for learning math and physics?

They are default policies that steer your study over weeks and decide what you do at key decision points: learn, not finish; treat difficulty as good; invest hours; balance exams with mastery; and help people who want help.

How do I know if my struggle is productive?

Productive struggle involves generating and testing: modeling, recalling, explaining, checking, and correcting. Unproductive struggle looks like looping without learning (staring, rereading, hunting for vague hints). That’s when you use support — then return and redo from memory.

Should I focus on grades or mastery?

Use both. Grades help you prioritize what the course will test. Mastery helps you build models that transfer and keep working after the exam.

How can helping others improve my own understanding?

When you help someone who’s trying, you’re forced to retrieve the idea, explain causal steps, and adapt to questions. That exposes weak links fast. A useful boundary: they show an attempt first, and they do the writing.

What should I do when I feel unmotivated to study?

Lower the entry cost and start with one honest attempt. Motivation often shows up after you begin. If you want a plan for starting more consistently and keeping motivation higher, see How to Stay Motivated Studying Math and Physics.

Is this just “growth mindset”?

Not really. Growth mindset is a broad belief that ability can improve. This guide is narrower and practical: it’s about policies that change what you do next when friction appears.

How This Fits in Unisium

Unisium is a mindset stress test. It forces retrieval, explanation, and hard attempts — the effortful behaviors that weak mindsets avoid. If you have the mindsets above, Unisium feels like productive training. If you don’t, it feels “too hard” and you bounce. That reaction is useful feedback: it tells you exactly which mindset to build next.

In the Unisium Study System, effective mindsets show up as behaviors: you attempt first, you use support strategically, and you redo from memory. That pairs naturally with elaborative encoding, retrieval practice, and self-explanation as a default loop.

Ready to try it? Start learning with Unisium or explore the full framework in Masterful Learning.

Masterful Learning

The study system for physics, math, & programming that works: encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, principled problem solving, and more.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →