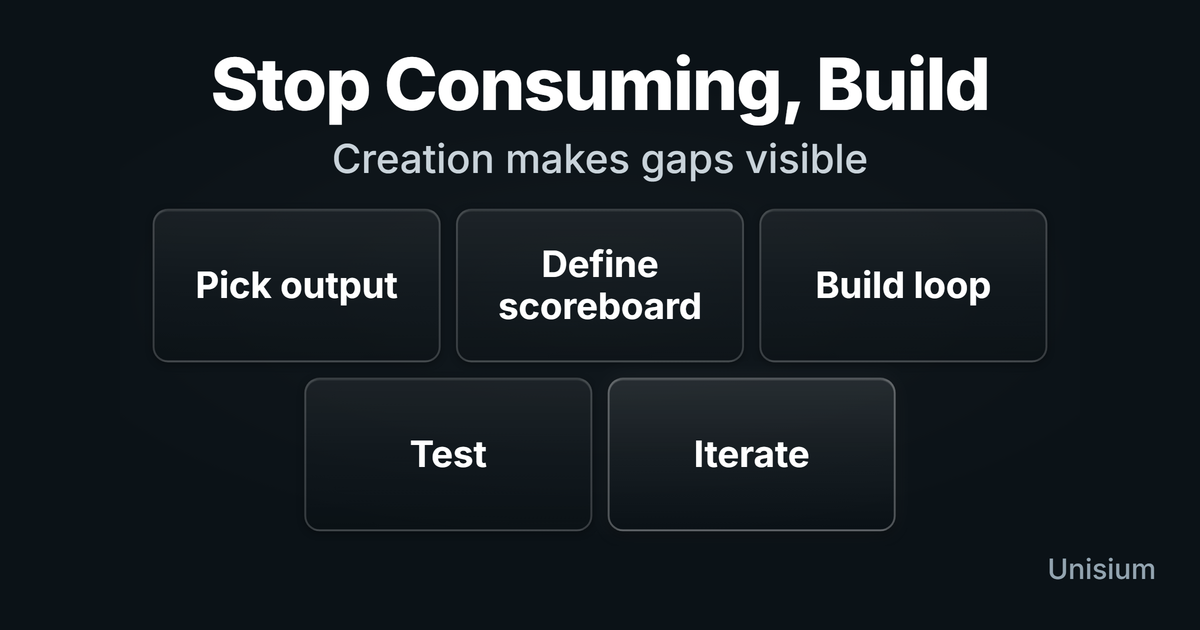

After Studying Math and Physics: Stop Consuming, Build

After studying math and physics, the next move is creation: build something that depends on the ideas (a model, tool, experiment, or product). Consumption has diminishing returns because it avoids decisions and hides gaps, while building creates tight feedback under real constraints. In the Unisium Study System, this is the bridge from studying well to producing real outputs.

If you’ve finished courses or a degree and feel stuck, it’s usually not a motivation problem. It’s a feedback problem. Reading, watching, and “learning more” gives weaker and weaker feedback over time. Building gives sharp feedback, real constraints, and a reason to keep improving.

To make the transition easier: if starting sessions is the bottleneck, fix your cues and tiny first actions (see Study Habits for Math and Physics). If you keep quitting mid-semester, build a motivation system around short feedback loops (see How to Stay Motivated Studying Math and Physics). If focus collapses once you sit down, use an entry script (see From Resistance to Flow).

On this page: The shift · Build-to-learn · Collaborate · Go beyond · Get experience · Mission · Common mistakes · Start now · FAQ

The shift: from consumption to creation

The point of studying is not to collect knowledge. It’s to produce: explanations, models, experiments, code, designs, and decisions. Creation sits at the top because it forces everything underneath it, and it’s the only level where gaps become unignorable.

Creation is the capstone because it requires the full stack: you must remember what you need, understand how it fits together, apply it under constraints, analyze what breaks, and evaluate tradeoffs. Then you can create an output that stands up outside your own head.

Creation forces the full stack:

- Remember what you need

- Understand how it fits

- Apply it under constraints

- Analyze what breaks

- Evaluate tradeoffs

- Create an output that survives contact with reality

Skeptical take: “I’ll build something once I know enough” sounds reasonable. It’s wrong. Building is the activity that reveals what “enough” means.

Want the complete framework behind this guide? Read Masterful Learning.

Build-to-learn after math and physics

A good project is not “impressive.” It has a scoreboard.

Pick an output that forces decisions and can be checked against reality: tests, limits, data, measurement, or a user.

1) Pick an output that has a scoreboard

Choose one of these four project types. They all create honest feedback.

A) Model / simulation — Example: pendulum with damping + driving, then compare to a phone video. Scoreboard: sanity checks, conserved quantities in special cases, known limiting behavior.

B) Measurement / experiment — Example: estimate with video analysis; measure drag effects; build a simple sensor rig. Scoreboard: uncertainty estimates, repeatability, error sources.

C) Data analysis — Example: fit a model to real data you care about (sports, energy use, finance, health). Scoreboard: out-of-sample error, residual structure, sensitivity analysis.

D) Tool / product — Example: a small app, script, or calculator that makes one task easier. Scoreboard: real usage, fewer steps, fewer errors, clearer outputs.

2) Define feedback before you build

Write down what “right enough” means before you start.

Examples include unit tests, comparisons to a known analytic result, dimensional checks, limiting cases, replication of a textbook plot, or measurement with uncertainty bounds.

This prevents you from confusing “busy” with “progress.”

3) Build the smallest working loop, then iterate

Start with an end-to-end loop that works badly, then improve one constraint at a time. A good iteration answers one question, not ten.

One workable sequence is: version 1 produces an output, version 2 matches a simple known case, version 3 remains stable under variation, and version 4 becomes useful to someone (including future you).

4) Convert failures into targeted study tasks

When your project breaks, don’t panic-read. Translate the failure into a concrete task: derive the equation and state assumptions, explain the model choice in plain language, implement the method cleanly, validate numerical behavior, or write the uncertainty budget.

This is where studying stops being abstract and becomes surgical.

If you want the underlying study mechanics, use the Core Four guide cluster as a map: retrieval practice, elaborative encoding, self-explanation, and problem solving.

If you want the full map, start at the guides hub.

Collaborate to keep momentum

Most solo projects don’t fail from difficulty. They fail from drift.

Collaboration fixes drift by adding deadlines, perspective, and accountability. Pick one: weekly 30-minute review with a peer, hackathon or student initiative, lab or research group, or a short public log (one screenshot, one plot, one paragraph per week).

Example (mine): After finishing a master’s in nuclear physics, I built an online course about learning with a friend, despite having no formal education in the topic. The project taught me more than more reading ever could: structure, production, editing, marketing, and finishing. That course has reached 22,000+ students with 7,400 reviews and an average rating of 4.6 out of 5 stars as of writing, and it eventually pulled me into a PhD and my career.

If you can’t find collaborators, use the smallest ask: “I’m building X. Want to do a 20-minute check-in on Fridays for 4 weeks?”

Go beyond what’s required (without burning out)

The people who get unusual outcomes usually do one unusual thing: they exceed the minimum. Not to impress anyone. To create options.

Two safe ways to stretch:

- Depth stretch: take one course topic and build something that uses it end-to-end.

- Load stretch (optional): if your life supports it, take a slightly heavier credit load for a semester to force efficiency.

Pick one stretch at a time. If you try depth stretch and load stretch and a project, you create guilt.

Rule: stretching is only useful if it stays sustainable. If your sleep, health, or relationships collapse, you are not “disciplined.” You are degrading the machine.

Get real-world experience

You want constraints. Constraints turn theory into competence.

Gain work experience

A summer job, part-time role, or internship in a relevant environment does three things: exposes what matters in practice, teaches collaboration and delivery, and gives you references and a network. Once you’re in, don’t coast. Constraints teach faster than courses.

If you can automate tasks, improve processes, or build internal tools, you become hard to replace.

Gain research experience

If academia is even a possible path, research experience is not optional.

Research teaches what exams rarely teach: measurement and instrumentation, uncertainty and error modeling, statistics that matter, programming and data pipelines, and scientific writing and methods. If you’re writing a thesis, aim for publishable quality as a forcing function for depth and structure.

Mission: take responsibility

A mission is not a motivational poster. It’s a constraint that makes your choices coherent.

If you can point your projects, internships, and reading at one direction for a year, you will look “talented” to other people. It’s usually alignment plus time.

To choose a mission without overthinking it:

- Pick the bottleneck: energy, materials, computation, measurement, or education.

- Pick the arena: industry, research, or open-source.

- Pick the artifact: one project you can ship in 4 weeks.

Examples of mission domains include clean energy, materials and recycling, climate mitigation, food and agriculture systems, zero-emission transport, and space and long-term infrastructure.

Read widely (popular science, papers, news, technical books) to build a library of problem patterns and solution patterns, then pick a responsibility you can bear. If you want a curated starting point, use the Essential Reading List.

Common mistakes (and fixes)

| Mistake | Fix |

|---|---|

| Choosing a project with no feedback | Add a scoreboard: limiting case, test, dataset, measurement, or user. |

| Waiting until you “know enough” | Start the smallest loop that runs end-to-end, then let gaps appear. |

| Treating features as progress | Track verified outputs: plots, tests, measurements, users. |

| Working alone until burnout | Add one lightweight collaboration mechanism (a weekly review is enough). |

| Staying in “student mode” forever | Ship artifacts. A portfolio is outputs, not intentions. |

| Making a portfolio that’s just screenshots | Publish one artifact with evidence: a repo + README + one reproducible result, a short report with uncertainty, or a write-up that makes falsifiable claims. |

Start now

The 10-minute start

- Choose an output (2 min) — “I will build X.”

- Choose a scoreboard (3 min) — “It counts if Y matches within Z.”

- Write the first loop task (5 min) — “By tonight I produce a plot/table/result.”

The 4-week plan

- Week 1: smallest loop, one plot, one check

- Week 2: validate against a known case

- Week 3: add one real constraint (noise, data, performance, usability)

- Week 4: write a short public summary (what worked, what broke, what you learned)

If you do this once, you stop being “someone who studied physics/math” and become someone who builds with it.

FAQ

What should I do after studying math and physics?

Build something testable that forces decisions: a model, measurement, analysis, or tool. It converts “I learned it” into “I can use it,” because you must justify assumptions and define correctness.

How do I choose a good project?

Pick one with an obvious scoreboard: tests, limiting cases, comparisons, or real data. Keep it small enough to finish a first version in days, but extendable for months.

Is it better to do a personal project, an internship, or research?

They train different constraint types: projects train iteration and ownership, internships train delivery and collaboration, and research trains uncertainty and methodology. Do one with tight feedback now, then use it to qualify for the next.

How do I collaborate if I don’t know anyone?

Make the ask tiny and specific: 30 minutes weekly for 4 weeks. You don’t need a team. You need a checkpoint.

What if I feel unqualified to build anything?

Start with a toy version that reproduces a known result. Your first goal is not novelty. It’s an end-to-end loop with a scoreboard.

How This Fits in Unisium

Build-to-learn is what you do once the core study methods are stable. You use the same loop from retrieval practice, self-explanation, elaborative encoding, and problem solving, but you aim it at an artifact with real constraints.

If you want the full structure for this approach, start with Masterful Learning and use the guide cluster above to implement it day-to-day.

Masterful Learning

The study system for physics, math, & programming that works: encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, principled problem solving, and more.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →