How to Study Physics and Math with AI (Without Letting It Think for You)

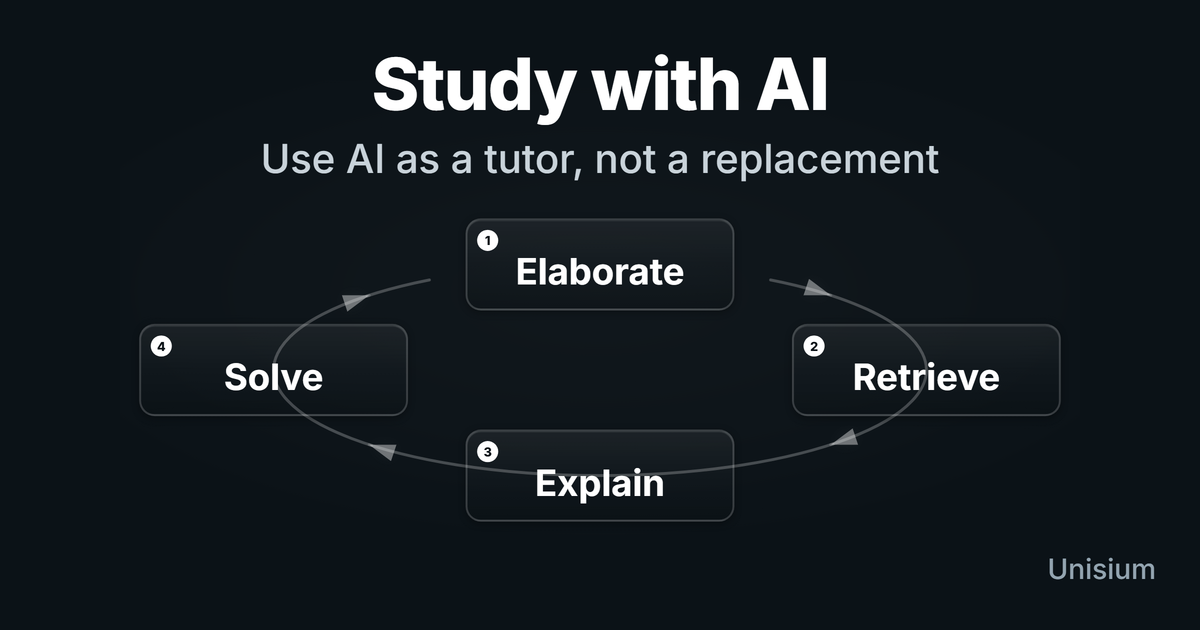

To study physics and math with AI, use it as a tutor for the four skills you must still build yourself: elaborative encoding (making concepts meaningful), retrieval practice (recalling without notes), self-explanation (justifying solution steps), and problem solving (choosing models and methods). This works because AI can generate questions, hints, and feedback on demand while you keep ownership of the reasoning on paper. If it starts producing full solutions you copy, you’re training comfort, not competence.

The question: If AI can already solve physics problems, explain math proofs, and write code, how should you study now?

You should treat AI as a powerful assistant for the core learning strategies—not as a replacement for them. You use it to deepen elaborative encoding, sharpen retrieval practice, scaffold self-explanation, and accelerate problem solving. The moment it starts doing the thinking for you, you’re trading long-term skill for short-term comfort.

Everyone else is writing “how to use AI to study” pieces that mostly push summarization, aesthetic notes, and passive clean-up of your materials. Those guides fit neatly alongside the strategies I argue against in Note-Taking During Lectures: Why It Fails (And What Works Instead), 6 Ineffective Study Techniques (and What to Do Instead), and Why Highlighting and Underlining Don’t Work (for Learning).

This guide assumes you care about being able to solve problems on your own, under exam pressure and in real work. AI is welcome only insofar as it amplifies the four primary strategies from Masterful Learning: elaborative encoding, retrieval practice, self-explanation, and problem solving.

Used this way, AI becomes one of the tools inside your study workflow rather than a replacement for it.

It also assumes something else: you’re studying physics and math. These are fields with hard constraints. Units either match or they don’t. Probabilities either sum to 1 or they don’t. Conservation laws are either respected or violated. That makes them ideal testing grounds for using AI without letting it quietly rot your ability to think.

On this page:

Key takeaways · The Core Rule · How LLMs Fit · Elaborative Encoding · Retrieval Practice · Self-Explanation · Problem Solving · Study Workflows · Guardrails · Prompt Patterns (Appendix) · FAQ

Key takeaways

- AI is a multiplier, not a brain replacement. Use it to make good strategies cheaper and easier, not to avoid thinking.

- Route everything through your core strategies. When you use AI, ask: Is this strengthening how I understand, recall, explain, or solve? If not, it’s probably procrastination.

- For physics and math, never outsource the hard step. Let AI handle explanations, hints, extra examples, and card generation; you do the recall, algebra, derivations, and decisions.

- Avoid passive consumption. Don’t just read AI’s answers—summarize them, challenge them, and turn them into questions and problems.

- Respect course rules and exam integrity. Use AI heavily for learning where it’s allowed; be strict about not using it to directly complete graded work.

The Core Rule: AI Must Sit Inside Your Learning Strategies

If you remember only one rule from this guide, make it this:

AI is only “allowed” to the extent that it strengthens elaborative encoding, retrieval practice, self-explanation, or problem solving.

Most mainstream “study with AI” advice is about summarizing articles and lecture notes, cleaning or reorganizing notes, drafting essays or lab reports, and turning slides into aesthetic flashcards. You can do all of that. It’s just not where the real leverage is in physics and math.

The big gains come from the cognitively expensive strategies: turning concepts into rich, meaningful structures (elaborative encoding), practicing recall under some form of pressure (retrieval practice), explaining worked solutions until you can see the moving parts (self-explanation), and using problems to convert principles into skills (problem solving). AI becomes dangerous when it replaces those. It becomes powerful when it lowers the friction of doing them.

A simple test cuts through most of the ambiguity:

If the AI disappeared right now, could you still reproduce the reasoning on paper?

If the answer is “no,” you’re probably letting it think for you instead of with you.

How LLMs Fit into Studying (Quick Demystification)

A large language model (LLM) is basically a huge mathematical function:

input tokens (pieces of text) → a lot of linear algebra and non-linearities → output tokens

Given some text, it doesn’t sit there and “understand” in the human sense. It computes which next token is most probable given the previous ones and everything it has seen during training. Then it repeats that process, token by token.

That has consequences.

What LLMs are good at

LLMs are extremely good at tasks that depend on surface pattern structure: generating fluent explanations in different voices and levels, summarizing longer texts (with some risk of omissions or distortions), producing plausible solutions to standard-looking problems, and generating questions, variants, and analogies on a theme. For a learner, that means explanations on demand, alternative phrasings, and essentially unlimited practice material.

What LLMs are bad at (especially in physics and math)

They are much weaker at knowing when they’re wrong, respecting hard constraints like units, conservation laws, or probability bounds over long chains of reasoning, keeping track of subtle conditions of theorems or principles, and deciding what matters in a messy real problem. They optimize for plausible text, not truth or physical consistency. That’s why you can get beautifully written nonsense: attractive derivations that violate energy conservation, probabilistic arguments where probabilities exceed 1, or solutions that quietly ignore limiting cases.

Your job is not to worship the output. Your job is to audit it.

Using AI for Elaborative Encoding

Elaborative encoding is about making meaningful connections: linking a concept to examples, contrasts, conditions, and prior knowledge. AI is an almost unfair tool for this—if you use it correctly.

Ask narrower, context-rich questions

“Explain conservation of energy” is an invitation for generic boilerplate. You get a vague, context-free explanation that might as well be copied from a textbook.

You get much more value from prompts like: “Explain the work-energy theorem for 1D motion with non-constant force, in the context of an introductory mechanics course,” or “Explain composition in Java as used in a basic data structures course, and contrast it with inheritance,” or “Explain the Mean Value Theorem in the context of velocity and position functions, not just abstract functions.” By specifying course, level, and subtopic, you constrain the model to work in a useful slice of its knowledge instead of wandering off into unrelated territory.

Layer explanations instead of hoarding them

Don’t ask for “the full explanation” and then screenshot 2,000 tokens into oblivion. A better pattern is to build understanding in layers.

First, ask for a short explanation in plain language, phrased for a first-year physics or math student at your level. Next, ask for a concrete numerical example that could have come from your own course. Then ask for a contrast with a nearby concept: how this principle differs from some other principle you often confuse it with. Finally, ask for a failure case: a situation where the principle does not apply and why.

Then stop. Close the AI tab. Rewrite the explanation in your own words, with your own example and your own contrast. That act of rephrasing and reorganizing is where most of the encoding happens.

Generate elaborative questions you answer yourself

One of the best uses of AI is question generation, not answer generation. You might ask:

“I’m studying [subtopic]. Generate a list of 10 elaborative questions that would help me understand it deeply. Focus on what it means, when it applies, how it fails, and how it contrasts with nearby ideas.”

Now the important part: answer those questions in a notebook or inside Unisium, without looking at the AI’s answers. Only afterward do you reveal what the model proposed, compare, and use the differences to refine your mental model. In this pattern, the AI proposes the questions; you do the thinking. That’s elaborative encoding, not content outsourcing.

It helps to think of each answer you write as a micro-hypothesis: a small bet about how the concept works. First you commit to your own explanation or definition. Then you paste it into the model and ask something like, “Where is this wrong, incomplete, or missing conditions?” The learning comes less from the AI’s wording and more from the clash between what you thought before and the revisions you’re forced to make.

How this looks in Unisium

In Unisium, elaborative encoding cards prompt you to answer elaborative questions first, and only then use AI to test, refine, or contrast your explanations.

Using AI for Retrieval Practice

Retrieval practice is about pulling information out of memory, not recognizing it when you see it. With AI, the key rule is simple:

Don’t look at the AI’s answer until you’ve produced your own.

Everything else is detail.

AI as an on-demand quiz generator

For a given topic, you can ask the model to generate a set of short-answer questions an instructor might ask on an exam at your level, and explicitly tell it not to include the answers yet. Then you hide the part of the chat where answers will appear, or scroll to keep them out of view, and answer each question from memory on paper or in a text editor. Only after you’ve committed to your answers do you reveal the model’s suggestions and compare.

The point is not that the AI’s answer is perfect. The point is that you have forced retrieval before exposing yourself to the canonical answer. After answering, you compare your responses to the AI’s. Where did you match exactly? Where did you use different words but capture the same idea? Where did you miss key conditions, units, or constraints? You can even ask the model to highlight what you’re missing or got wrong and to rate your answer as correct, partially correct, or incorrect—but the work of reading, interpreting, and deciding what to change remains yours. In this mode, the AI is a reviewer, not a replacement.

Turn good questions into spaced flashcards

Some of the AI-generated questions will be excellent flashcards. Don’t assume you’ll “find them later” in a chat log. Pick the best questions and turn them into actual cards in Anki (see How to Study Physics and Math with Anki) or Unisium. Keep answers short and focused—formula, conditions, one key example—and use the AI’s longer answer only as a reference to refine your short version, not as something you try to memorize verbatim. AI makes card creation cheap; retrieval practice still has to be done the hard way.

How this looks in Unisium

Retrieval cards in Unisium are strictly “you answer first”; AI can help generate extra questions or critique your answers, but it never reveals answers by default.

Using AI for Self-Explanation

Self-explanation is the process of walking through a worked solution and explaining why each step is valid and which principle makes it legal. AI is strong at acting as a “structure annotator” for solutions—as long as you keep control.

Have AI mark up the structure of a solution

Take a worked example from your textbook or notes and ask:

“Here is a worked solution. Identify, step by step, which physics/maths principles are being applied, and state the conditions for each principle. Don’t change the solution; just annotate it.”

You’re asking the model to label things like, “Here we apply conservation of mechanical energy assuming no non-conservative work,” or “Here we use Newton’s second law in the radial direction, assuming uniform circular motion,” or “Here we use the Mean Value Theorem, which requires continuity on [a, b] and differentiability on (a, b).” The result is a principle-level map of the solution.

Once you’ve seen the annotated version, close it and write your own explanation of the same solution from scratch: which principles you’re using, why they apply, and what would break if assumptions changed. Then paste your explanation and ask the model to compare it with the annotated one and point out where you’re vague, wrong, or missing important conditions.

In that setup, the model behaves like a picky teaching assistant. You still do the explaining.

How this looks in Unisium

Self-explanation prompts in Unisium guide you to break down solutions step-by-step into principle, conditions, and goal, building retrievable solution rules.

Generate contrastive examples

You can push this further by asking for a similar problem where the surface structure looks the same but a different principle applies—for example, a problem where energy methods fail and you must use momentum, or a problem where a theorem no longer applies because its conditions are violated. You then solve that new problem and self-explain again. This trains you to notice when surface similarity hides deeper differences, which is a core skill in physics and math and something LLMs routinely struggle with.

In all of this, you’re not passively reading AI explanations. You’re running an interactive loop: predict, answer, check, revise. That’s the same hypothesis-driven learning process laid out in Masterful Learning, just with an unusually responsive study partner.

Using AI for Problem Solving (Without Cheating)

Problem solving is where things go off the rails quickly. It’s all too easy to paste a physics or math problem into an AI solver and get a full solution with pretty explanations. There are now tools built explicitly to encourage that behavior.

The temptation is obvious. The damage is slower and less obvious: after a while, you start to feel that you “know the material” because you could get the solution if you wanted. On exams or in real work, there is no autocomplete.

The “hint ladder” instead of full solutions

When you’re stuck, don’t jump straight to “solve this problem.” Use a hint ladder:

- You restate and attempt first. Write down what the problem is asking, the given data, and your first attempt at a solution.

- Ask for the next nudge, not the full path. For example: “I’m stuck after this step. Which principle should I consider next?” or “What’s a good intermediate quantity to solve for here?”

- You implement the hint. Take the hint, write the next step yourself, then see if you can finish from there.

- Ask for a check. Only then do you ask: “Here’s my full solution. Check whether my choice of principles and conditions makes sense; ignore small algebra glitches.”

The sequence is always: you think → AI nudges → you think again. The AI never owns the solution end-to-end.

Debugging your own attempts

When you do ask the AI to look at a full solution, narrow what you want. Instead of “find my mistake,” ask it to check only whether you violated any conservation laws, whether units are consistent in each equation, or whether any theorem or method is used outside its conditions. You’re forcing the model to act as a constraint checker, not a magic oracle. That’s much closer to how you’d use a good human tutor.

Projects and coding: don’t become a vibe coder

If your physics or math courses include programming—numerical methods, simulations, data analysis—AI can feel like a superpower. It scaffolds boilerplate, suggests library calls, and can write entire functions. The risk is becoming a vibe coder: you paste prompts, it spits out code, and you never really know why it works—or why it broke.

To avoid that, use AI to propose designs but commit to writing the critical paths yourself in at least one project. Ask it to critique your architecture (“Does this follow SRP?”) rather than invent it whole. And when there’s a bug, resist the urge to ask “fix this” and instead ask for likely causes, then go investigate them yourself. You’re training the meta-skills—architecture, debugging, constraint awareness. Those are exactly the parts the model can’t reliably own for you.

How this looks in Unisium

Problem-solving cards in Unisium track whether you solve the problem without seeing a full solution. After submitting, you can ask AI about your problems solving strategy and drawings.

Putting It Together: Study Workflows for Physics and Math

So what does all of this look like across a typical week? Think in terms of phases: before class, after class, problem sets, and weekly review.

Before class: map the territory

Suppose you’re about to start a unit on rotational dynamics or on sequences and series. Before the first lecture, you use AI to get a short, level-appropriate overview of the topic and to identify the five to seven core principles or theorems that usually appear there. You might also ask for a handful of diagnostic questions you should be able to answer once you’ve understood the section well.

You’re not trying to master the topic in advance. You’re building a mental scaffold so lectures and problem sets have somewhere to land.

After class: elaboration and self-explanation

That same day, you use AI to clarify what didn’t make sense in lecture. You describe where you got lost and ask targeted questions rather than “explain the whole chapter.” Then you pick one worked example from the textbook or slides and have AI annotate it with principles and conditions. After that, you close the annotations and self-explain the solution in your own words.

This is the phase where “I saw it once” becomes “I understand what is happening and why.”

Problem-set days: retrieval first, AI as a scaffold

When the problem set arrives, you don’t start by throwing the hardest problem into ChatGPT. You warm up with retrieval practice: ask AI for a small set of short questions on the key principles and answer them from memory. Then you attempt the assigned problems cold, without assistance.

Only after you’re stuck on a specific step do you reach for the hint ladder. If your default move is to paste entire problem statements into AI, you’re not practicing problem solving—you’re practicing copy-paste and prompt writing.

Weekly review: mock oral exam

Once a week, you turn AI into an examiner. You ask it to pose a sequence of increasingly challenging conceptual questions about the topics you’ve covered that week, one at a time, and to wait for your answer before responding. You answer aloud or in writing, then you ask for a critique that focuses on missing conditions, sloppy language, or incorrect reasoning.

Over time, this reveals where your understanding is vague or brittle, even if your written homework has looked fine.

Guardrails: When (and When Not) to Use AI

Surveys in 2024–2025 suggest that a large majority of students now use AI for coursework in some way, often weekly or daily. Most aren’t getting explicit guidance on how to use it without sabotaging their own learning.

A few simple guardrails go a long way.

Good uses are those where AI reduces friction for strategies you already know are effective. That includes clarifying concepts with targeted, context-rich questions; generating elaborative questions you then answer yourself; creating practice questions for retrieval and mock exams; annotating worked examples with principles and conditions; and giving feedback on explanations or proofs you’ve written.

Bad uses are those where AI quietly replaces the actual cognitive work. That includes asking it to directly solve assigned problems and handing in its solution, letting it write lab reports, essays, or code you submit as your own, treating it as a calculator for every routine derivation instead of practicing, and using it during closed-book or restricted exams in violation of course rules. If you feel a little guilty while you’re doing it, that’s usually a signal.

You can also watch for symptoms of overuse. If you can’t solve exam-style problems without “just checking one thing with ChatGPT,” if you feel lost when asked to derive something from first principles on paper, if you can’t explain a solution without reading from AI-generated text, or if you notice your patience for slow, careful reasoning getting shorter, you’re on the brain-rot trajectory: things are still getting done, but your actual capacity to think is decaying.

Finally, academic integrity. Universities and courses are now writing explicit AI policies. Some allow AI for idea generation and concept clarification but not for writing or solving assessed tasks. Some allow it with explicit citation. Others ban it outright for all assessed work. You can disagree with a policy, but you shouldn’t ignore it. Use AI freely for learning when permitted; be conservative whenever graded work or professional ethics are in play.

For instructors: how to frame AI in your course

If you’re teaching physics or math, the core message you want students to hear is simple: AI is welcome when it helps them practice the core strategies outlined earlier in the guide, and unwelcome the moment it starts doing those for them. If you want a ready-made environment that enforces these norms for your physics or math course, the Unisium Study System is built exactly for that: it bakes elaborative encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, and problem solving into the study flow, with AI kept in a strictly supportive role. Pointing them to this guide—or borrowing some of the wording for your syllabus—can save you from having the same “good vs bad uses of AI” conversation dozens of times.

Appendix: Prompt Patterns You Can Steal

Up to now I’ve focused on principles and workflows. If you want concrete prompt templates you can paste into your AI tool of choice, here are some starting points.

Elaborative encoding prompts

I’m a first-year physics/math student taking [course].

Explain [concept] in the context of [specific subtopic], not in general.

First, give a short explanation in plain language.

Then give one numerical example at my level.

Then give a contrast with [related concept].

Then list 3 questions I should be able to answer if I truly understand it.Retrieval practice prompts

I’m studying [course, level].

Generate 15 short-answer questions that an instructor could ask on an exam

about [specific topic]. Mix basic definitions, conditions of use,

and conceptual "why" questions.

Do NOT include answers yet. Wait for me to answer before revealing them.Self-explanation prompts

Here is a worked solution from my textbook.

Annotate it step by step:

- Which principle or theorem is being used in each step?

- What are the conditions for using that principle?

- Are those conditions satisfied here?

Don’t change the solution; just mark it up.Later:

Here is my own explanation of the same solution.

Compare my explanation to the annotated one.

Point out where I’m vague, missing conditions, or reasoning incorrectly.

Be specific but concise.Problem-solving / hint-ladder prompts

Here is a physics/math problem and my attempt so far.

1) Tell me whether my setup (knowns, unknowns, chosen principles) makes sense.

2) If I’m stuck, give me only the next nudge:

- which principle to apply next, or

- one useful intermediate quantity to compute.

3) Do NOT give the full solution unless I explicitly ask for it later.Adapt the level and tone as needed. The pattern stays the same: you own the thinking; AI nudges and critiques.

FAQ: Using AI to Study Physics and Math

“Can I use ChatGPT to do my physics homework?”

You can. Many students do. The better question is what you’re trying to achieve. If your goal is to get through this week’s problem set with minimal effort, AI will help. If your goal is to be able to solve novel problems on an exam or in real work, you already know from earlier in the guide why outsourcing the hard steps is a bad trade.

Use AI heavily to understand problems, generate variants, and debug your own attempts. Just don’t let it become your default problem-solving engine.

“Is using AI to study considered cheating?”

It depends entirely on your course and institution. Some courses allow AI for idea generation and concept clarification but not for writing or solving assessed tasks. Some allow it with explicit citation. Some ban it outright for all assessed work. For ungraded practice and self-study, most instructors would be happy that you’re using tools that help you learn—as long as you’re not bypassing the cognitive work.

When in doubt, ask, and err on the side of transparency.

“How do I know if the AI is wrong in physics or math?”

You develop internal alarms. Unit checks tell you whether dimensions match on both sides of each equation. Extreme cases tell you whether the answer behaves sensibly when inputs become extremely large or extremely small. Conservation checks tell you whether energy, momentum, charge, or probability mysteriously appear or disappear. Condition checks tell you whether the theorems or methods used apply to the functions and intervals at hand.

On top of that, you cross-check with textbooks, lecture notes, and simple approximations you can do by hand. Treat the model’s answer as a hypothesis to test, not a fact to accept.

Can AI replace a tutor?

For some roles, yes. AI can explain concepts over and over without getting tired, quiz you at any hour, and generate endless practice problems at roughly the right level. But a human tutor still has edges: noticing when you’re demotivated rather than confused, picking up on subtle misconceptions across multiple sessions, and knowing the specific quirks of your course and exams. (For how to use lectures, workshops, and office hours alongside AI, see How to Use Lectures, Workshops, and Other Learning Offers Effectively).

You don’t have to choose. Use AI as a first-line tutor. Use humans when you’re stuck at deeper layers.

“Is there any app that already implements this way of using AI?”

Yes, Unisium. (If you want to see whether it’s a fit for you, read Is Unisium Right for You?.) It’s a physics and math learning app built around this exact philosophy: using AI as a tutor and critic inside the four core strategies (elaborative encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, problem solving) rather than as a solver that replaces them.

“Which AI tools should I use?”

The exact brand matters less than you think. Use at least one strong general-purpose LLM (ChatGPT, Claude, etc.), and if possible, modes or settings explicitly designed for studying rather than instant answers (Socratic or “study” modes). Stick with a setup long enough that you can refine your prompting and workflows. The bottleneck is not the tool. It’s whether you route its power through the right strategies.

Related Learning Guides

If you want to go deeper on the core strategies that AI should be amplifying, see:

- Elaborative Encoding: Learn Faster with Better Connections — Make principles meaningful so they stick.

- Retrieval Practice: Make Knowledge Stick (Faster) — Keep principles accessible so you can use them.

- Self-Explanation: Learning from Worked Solutions — Turn examples (including AI-generated ones) into reusable rules.

- Problem Solving: The Learning Strategy That Turns Knowledge into Skill — Where you train automation, judgment, and transfer.

- Note-Taking During Lectures: Why It Fails (And What Works Instead) — If you’re using AI to pretty-up notes, read this first.

- 6 Ineffective Study Techniques (and What to Do Instead) — A broader look at what to stop doing in the AI era.

How This Fits in Unisium

Unisium bakes these patterns into study sessions so AI stays in a supportive role: you answer first, explain your reasoning, and then use AI as a critic, hint generator, and constraint checker. That’s the Unisium Study System applied to physics and math tasks where units, conditions, and modeling choices matter. Ready to try it? Start learning with Unisium or explore the full framework in Masterful Learning.

For the full framework behind these strategies, see Masterful Learning.

← Prev: Why Study Math and Physics in the Age of AI? | Next → Elaborative Encoding

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →