Why Highlighting and Underlining Don't Work (for Learning)

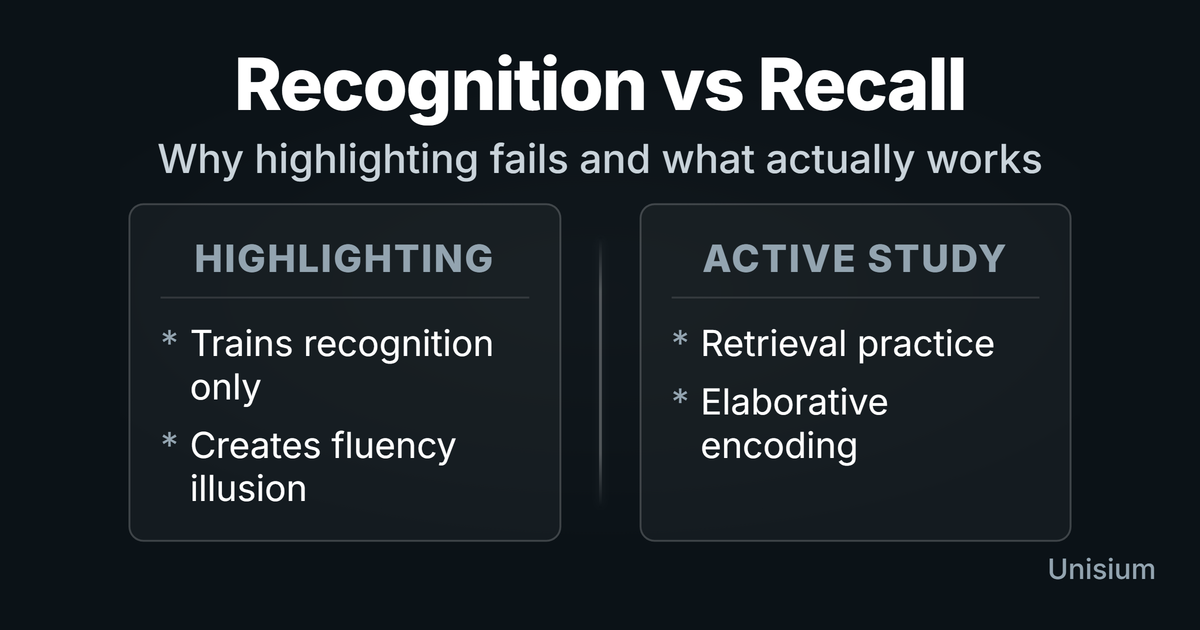

Highlighting and underlining are weak study methods because they train recognition (“I’ve seen this”) instead of recall and application under pressure. They feel productive because you’re selecting text, but you’re not generating explanations, links, or retrieval—so you get fluency without durable knowledge. Use highlighting only as bookmarking for writing/projects; for learning, switch to elaborative encoding, self-explanation, and retrieval practice.

Highlighting and underlining don’t work for learning—even though they feel active. You practice making decisions about “what’s important,” but you don’t practice what matters: understanding relationships, retrieving under pressure, or solving problems.

Recognition is not recall. Familiarity is not understanding.

Why highlighting doesn’t help learning comes down to a simple mismatch: you’re training the wrong skill. Exams don’t ask you to find highlighted sentences—they ask you to recognize structures, know when principles apply, and solve new problems.

Bottom line: Highlighting builds familiarity, not retrievable knowledge. The time spent coloring is time not spent on strategies that work.

On this page: TL;DR · Why it fails · When it might help · What to do instead · FAQ · How This Fits

TL;DR

- Recognition ≠ recall. Highlighting builds familiarity, not retrievable knowledge.

- Low cognitive strain. It avoids the hard work (explaining, linking, testing), so you get the illusion of learning.

- Wrong target. Exams don’t ask you to find highlighted sentences. They ask you to recognize structures, know when principles apply, and solve new problems.

- Principle of specificity: You learn what you practice. Highlighting practices labeling; learning requires generation, explanation, and testing.

Use instead: Elaborative Encoding, Self-Explanation, and Retrieval Practice.

These strategies form one of the core loops inside the Unisium Study System.

For a broader look at the passive techniques that steal time and what to do instead, see 6 Ineffective Study Techniques (and What to Do Instead).

Why Highlighting and Underlining Underperform

1) They Reward Selection, Not Understanding

You practice marking lines with a highlighter. Your brain gets trained at identifying candidate text—not at building models, extracting principles, or linking concepts. The outcome: a book with neon stripes and a brain with shallow traces. Using a highlighter looks productive. It’s not.

2) They Delay Thinking

Highlighting defers the elaboration you need to do now:

- What does this mean, precisely?

- When does it apply?

- How does it differ from related ideas?

You tell yourself “I’ll think about it later,” then never do the hard pass. The highlighting becomes a procrastination device—fix the start without willpower.

3) They Inflate Confidence

On the second read, highlighted text looks familiar → fluency illusion → overestimation of preparedness. You’ve seen it before. It feels like you know it. This is one of the big learning myths that quietly derails progress.

But: Familiarity is not understanding. Recognition is not recall.

4) They Don’t Map to Performance

There are no exact sentences to reproduce on exams. Performance requires:

- Recognizing problem structures and principles

- Knowing conditions of use (when principles apply, when they don’t)

- Executing procedures (solving novel problems)

Highlighters train none of that.

The Illusion of Productivity

Highlighting feels productive because:

- You’re making micro-decisions (important? yes/no)

- You’re creating a visual artifact (a marked-up textbook)

- You’re doing something while reading

But effort and learning are decoupled. You learn what you practice. Highlighting practices selection and aesthetics. Learning requires generation, explanation, and testing. Like other ineffective study methods, it trades the illusion of work for actual learning.

Switch Your Strategy

You have ~30 minutes per section. Spend it on approaches that work:

1) Elaborative Encoding (2–3 minutes per concept)

After reading a paragraph, answer three questions:

- What does this mean? Define it in your own words.

- When does it apply? What conditions make it valid? What would violate it?

- How does it differ? What’s the contrast with related ideas?

Link to one concrete example. See: Elaborative Encoding.

2) Self-Explain One Worked Example (5–10 minutes)

Walk through a solution and explain why each step follows from a principle and its conditions—not just what happens.

This bridges understanding to application. See: Self-Explanation.

3) Retrieve Without Notes (3–5 minutes)

Name → Form → Conditions → Contrast → Example.

Test yourself on key principles before consulting notes. Three clean recalls today; space tomorrow. See: Retrieval Practice.

When Highlighting Can (Narrowly) Help

Information retrieval for projects/writing. Mark passages you’ll cite later. This is document management, not study. Acceptable use case.

Anchors for navigation. If you must highlight, mark only key definitions and principle names—minimal landmarks for later active work.

Signal: If you’re coloring more than 5–10% of a page, you’re decorating, not thinking.

Quick Comparison: Highlighting vs. Effective Alternatives

| Goal | Highlighting | Effective Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Understand meaning | Weak (labels only) | Strong: Elaborative Encoding questions |

| Know when it applies | None | Strong: Conditions during self-explanation |

| Recall under pressure | Weak (recognition only) | Strong: Retrieval Practice with spacing |

| Solve new problems | None | Strong: Problem Solving + Five-Step Strategy |

FAQ

Should I stop highlighting completely?

For learning, yes. Use highlights only as bookmarks for projects. For studying, redirect the time to elaboration, self-explanation, and retrieval. Why highlighting doesn’t work for studying is simple: you’re practicing the wrong skill.

What if highlighting keeps me engaged while reading?

Use margin prompts instead. Write a 5-word question in the margin (e.g., “When does this fail?” or “What condition makes this true?”). Then answer it aloud. Engagement via thinking, not ink.

Is color-coding ever useful?

Only as a visual support for structure you already understand. For example, color by principle type (definitions in green, conditions in yellow, examples in blue) after you’ve encoded the content. Never as a substitute for understanding.

What if my professor says highlighting is important?

That’s a signal about what your professor values—not what your brain needs. Your professor likely wants you to be selective when citing sources for papers (reasonable). For learning? The research is clear: highlighting underperforms.

How This Fits in Unisium

Unisium bakes the “do work that transfers” idea into the study flow: instead of marking text, you’re prompted to explain concepts, state conditions, and retrieve from memory on a schedule. That’s the Unisium Study System applied to real physics and math tasks, not passive rereading. Ready to try it? Start learning with Unisium or explore the full framework in Masterful Learning.

Related Guides

- Elaborative Encoding — Build meaningful connections that enable recall and transfer.

- Self-Explanation — Turn worked examples into retrievable solution rules.

- Retrieval Practice — Make knowledge fast and durable through spacing and recall.

- Problem Solving — Turn principles into automatic skill through deliberate practice.

- Five-Step Strategy — A physics-specific framework for systematic problem-solving.

- Note-Taking During Lectures — Why this popular strategy also fails—and what works instead.

← Prev: Note-Taking During Lectures | Next → Elaborative Encoding

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →