How to Study Physics and Math with Anki (Without Memorizing Trivia)

To use Anki for physics and math, make cards that force you to recall definitions, conditions, and methods you apply in problems—not isolated formulas or trivia. It works when reviews trigger retrieval practice and brief self-explanation, so you rehearse “when/why to use this” under time pressure. Use Anki in low-focus time to keep core principles warm, and spend your best hours solving problems.

The problem: Standard Anki advice—“keep cards short, simple, and atomic”—is excellent for vocabulary and medical facts, but it is insufficient for physics and math.

How should you use Anki for physics and math?

Use Anki to repeatedly practice the principles and methods you rely on when solving problems, not isolated formulas. Focus your cards on three things: explaining concepts in your own words (elaborative encoding), recalling definitions, conditions, and key relationships (retrieval practice), and rehearsing solution strategies for standard problem types (self-explanation). Avoid huge decks of trivia and use Anki during low-quality time; use your best focus hours for real problem solving.

Most people never adjust their card design when they move from vocabulary to physics and math.

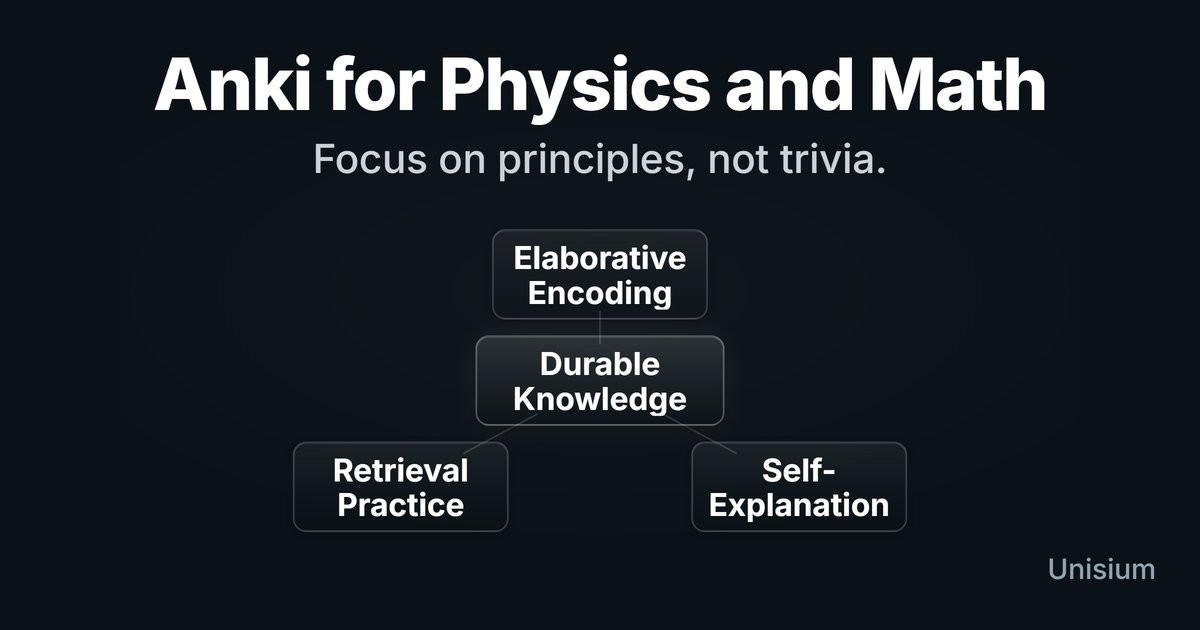

But Anki is just a scheduling engine. If you change what you put into it, it can be a powerful tool for three of the core learning strategies: elaborative encoding, retrieval practice, and self-explanation.

This guide covers how to wire Anki specifically for math and physics, how to use it to support problem solving, and where its limits lie compared to a dedicated system like Unisium.

That dedicated environment is the Unisium Study System, which bakes these principles into your daily study flow.

On this page:

Why Standard Advice Fails · The Core Strategy · Card Types for Physics & Math · Workflows · Anki + AI · Common Mistakes · Where Anki Stops · FAQ · How This Fits

Why Standard Anki Advice Fails for Math and Physics

You may have heard the golden rules of Anki:

- Make cards atomic (one fact per card).

- Keep answers extremely short.

- If you can’t answer in <10 seconds, the card is bad.

In physics and math, “atomic facts” are rarely the goal. The goal is to understand principles, conditions, and methods, and to know when to apply them.

If you atomize everything, you lose the context. You might memorize that , but fail to remember when it applies (inertial frames, particles) and when it fails (systems with internal motion, relativistic speeds). You become a master of trivia but freeze up on exam problems.

To make Anki work for these subjects, you have to break the “minimalism” rule. What matters isn’t whether a card is short. What matters is whether the card forces you to think.

The Core Strategy: Encoding, Retrieval, Explanation

Instead of asking “Is this card short?”, ask: “Which learning process does this card trigger?“

1. Elaborative Encoding (Understanding Deeply)

Elaborative encoding is about connecting new information to what you already know. Anki can support this by prompting you to explain why and how, not just what.

The card. Ask “Why?” or “Compare X and Y” instead of just “Define X.” For example, “Compare the dot product and cross product in terms of their geometric meaning.”

The answer. It can be longer. Put the core explanation on the front if you want to distribute your learning (re-reading and connecting ideas over time), or on the back if you want to test yourself first.

The goal. Each review refines your mental model, rather than just checking if you can parrot a definition.

2. Retrieval Practice (Building Fluency)

This is Anki’s home turf. Use it for the core building blocks you need to access instantly while solving problems.

The card. Focus on definitions, conditions of theorems, key relationships, and standard values.

The format. Cloze deletion is excellent here. Instead of “What is the formula for kinetic energy?”, use “Kinetic energy is valid for {{c1::point particles}} in {{c2::inertial frames}}.”

The goal. To make the basics automatic so your working memory is free for hard problem solving.

See Retrieval Practice for how to run these sessions and Spacing for how to schedule them effectively.

3. Self-Explanation (Internalizing Solutions)

Self-explanation is about learning from worked solutions, not turning Anki into a mini problem-set app. You use the card to walk through a structured solution and explain each step to yourself, especially the model steps you’re uncertain about. See Self-Explanation and the Five-Step Strategy for the full framework.

The card. The front shows a fully worked solution to a problem—ideally structured after the five-step strategy (model, principles, conditions, algebra, goal)—but without step-by-step explanations. You see the equations and steps, not the commentary.

The task. Go through the solution slowly and explain each step in your own words:

- Which principle is applied here?

- How do you know its conditions are satisfied?

- How is the model set up (forces, constraints, reference frames, variables)?

- How does this step move you closer to the stated goal?

Any step you can’t explain cleanly is a signal to pause, think, and, if needed, consult your notes or textbook.

The back. Short explanations or labels for each step: principle, conditions, and what that step is achieving. This is feedback, not something you stare at first.

The goal. To internalize solution patterns at the level of principles and modeling decisions, not just algebra. You keep rescheduling the card until every step makes sense. Once you genuinely understand the whole chain, you can safely delete or suspend the card—you’ve extracted the pattern you needed.

Card Types That Work

Here are specific templates you can copy for physics and math.

The Principle Card

- Front: “State the Mean Value Theorem in your own words, including the necessary conditions.”

- Back:

- Definition: If is continuous on and differentiable on , there exists a in such that .

- Conditions: Must be continuous on closed interval, differentiable on open interval.

- Meaning: Instantaneous rate of change equals average rate of change at least once.

The “Concept → Method” Card (Heuristics)

- Front: “You are given a system with a variable force and need to find velocity at position . Which principle do you check first?”

- Back: Work-Energy Theorem.

- Why: Force is a function of position, not time. Newton’s 2nd law would require integrating acceleration, which is harder.

The Cloze Relationship Card

- Text: “Angular momentum is conserved only when

{{c1::the net external torque}}is{{c2::zero}}.” - Text: “For a continuous function on a closed interval , the Extreme Value Theorem guarantees the existence of

{{c1::a global maximum and minimum}}.” - Note: Focus on the conditions and implications, not just the names.

The Self-Explanation Card (Worked Solution)

-

Front: Problem statement + worked solution, laid out in a clear structure (ideally following the Five-Step Strategy). For example: a block–pulley system with the full algebraic solution, but no textual explanations.

-

What you do when reviewing:

- First, read the problem and recall the overall goal.

- Then move through the solution line by line and self-explain: identify the principle in each step, check that its conditions are met, and state why that step is legitimate and helpful.

- Any step you can’t justify is a red flag to revisit that concept or principle.

-

Back: Brief annotations for each step, e.g.

- Draw FBDs for block and mass — modeling step, choosing coordinates along motion.

- Apply Newton’s 2nd Law in tangential / vertical directions — principle + conditions (point particles, inertial frame).

- Relate accelerations and tensions via constraint — modeling assumption (massless rope, ideal pulley).

- Solve the linear system for — algebra tying the model to the goal.

Once you’ve reached the point where you can reconstruct these explanations without the back side, the card has done its job. Suspend or delete it and move on to new problems.

Workflows for a Single Course

How do you fit this into a semester?

Before the Semester (Pre-learning)

Goal. Build a “skeleton” of the subject so lectures make sense. Find a high-quality shared deck for the subject (e.g., “Intro Calculus” or “Mechanics”).

Focus. Learn the definitions and main theorems before you need them. Don’t worry about solving hard problems yet. When the lecturer says “Gradient,” you should already know what it is so you can focus on the application.

During the Semester (Distributed Learning)

Daily Routine. Clear your reviews in 10–15 minutes. If the daily loop doesn’t start reliably, fix the start without willpower. Use “trash time”—waiting for the bus, sitting on the train, or the 5 minutes before class starts.

After Lectures. Create 3–5 high-quality cards based on the new material. Focus on principles and “why” questions.

The Rule of Three. If you have to look up a formula or rule three times while solving problems, stop and make a card for it. Your brain is telling you it’s important but not sticking.

Pre-Exam (Pruning & Focusing)

In the last week before a major exam, Anki should move into the background. Your main job is to solve difficult problems, preferably past exam problems, using the Five-Step Strategy and self-explanation.

1 Week Out. Stop adding new cards. Don’t chase a perfectly empty review queue if it eats into problem-solving time. Use Anki only in low-quality moments (commute, waiting rooms) to keep core principles warm.

Prune aggressively.

- Suspend or delete trivial cards and anything that doesn’t map clearly onto real exam tasks.

- If a card is vague, confusing, or stressful this late, it’s a bad fit—drop it rather than letting it drain attention.

Live in problems. Spend your best focus hours on multi-step problems and old exams, not on flashcards. Use Anki to support that work (e.g., for principles you keep forgetting), but don’t let it replace it.

When mixing problem types in that week, interleave topics deliberately so you practice choosing methods, not just executing them. See Interleaving for a simple rotation pattern.

Using AI to Supercharge Card Creation

Creating good cards takes time. AI (like ChatGPT or Claude) can speed this up significantly—see How to Study Physics and Math with AI for the broader framework.

Prompt for Principle Cards (Retrieval).

I’m studying [Topic, e.g., Electromagnetism]. Generate 5 Anki flashcards for [Concept, e.g., Gauss’s Law]. Focus on the conditions for validity, common pitfalls, and conceptual understanding. Use LaTeX for math. Keep each back short enough to recall in a few seconds.

Prompt for Concept Explanation Cards (Elaborative Encoding).

Explain [concept, e.g., dot product vs cross product] in the context of [use-case, e.g., calculating work and torque]. Write a short explanation that could go on an Anki card, and include one concrete example. Do not turn it into a full page of text.

You can then trim or adapt these outputs into principle cards (short backs) or elaborative cards (slightly longer fronts/backs), depending on where you put the explanation.

Prompt for Self-Explanation Cards (Worked Solutions).

Here is a worked solution to a physics/math problem.

- Rewrite it using the Five-Step Strategy: model, principles, conditions, algebra, goal.

- For each step, give a one-sentence note stating which principle is used, which conditions matter, and what the step achieves.

- Do not change the actual algebra.

Use the structured solution itself on the front of the card and the one-sentence notes as feedback on the back, exactly as in the self-explanation section above.

Formatting.

You can ask AI to format the output as a CSV file that you can import directly into Anki, preserving LaTeX formatting (e.g., $x^2$ or in Anki’s format \\( x^2 \\)).

The Golden Rule. Don’t let AI design your entire deck. Use it to draft cards, then edit ruthlessly so each card still fits one of the three purposes in this guide. Also, AI can hallucinate—always verify formulas and definitions against your textbook before adding them.

Common Failure Modes

1. The “Trivia Trap” You have 2,000 cards, but they are all simple facts like “Unit of Force = Newton.” You feel productive, but you fail the exam because you can’t apply the concepts.

- Fix: Add “Method” and “Self-Explanation” cards.

2. The “Bloated Deck” You download a massive shared deck and get overwhelmed by 500 reviews a day. You quit. If you start strong and then drop the system, build a motivation system.

- Fix: Be picky. Suspend cards you don’t need. It’s better to have 100 great cards than 1,000 mediocre ones.

3. Passive Review You flip the card, read the back, nod, and think “Yeah, I knew that.” (You didn’t.)

- Fix: Say the answer out loud or scribble it on paper before flipping. If you can’t articulate it, you don’t know it. Hit “Again.”

Where Anki Stops

Anki is good at one thing: showing you the right card at roughly the right time. It doesn’t know what a “principle” is, which problems matter most in your course, or how confident you are on a given topic beyond “I pressed Good/Again.”

That’s fine if you enjoy designing your own decks and workflows. With the patterns in this guide, you can get a long way just by combining Anki with a solid textbook and some discipline.

If you’d rather have the structure handled for you—what to study when, which principles are weak, how retrieval, self-explanation, and problem solving fit into a single session—that’s the gap Unisium is built to fill. It takes the same learning strategies you’ve seen here and bakes them into a progression system for physics and math, instead of leaving everything inside isolated cards. The Unisium Study System turns these strategies into concrete cards and scheduled sessions for you, so Anki can stay a flexible companion instead of your only backbone.

For the full theoretical background on why these strategies work (and how to combine them beyond flashcards), see Masterful Learning. This guide is just one small slice of that framework applied to Anki.

FAQ

Is Anki good for physics and math?

Yes—if your cards target principles, conditions, and methods, not isolated facts. The goal is fast retrieval of the building blocks you need while solving problems, plus occasional self-explanation to learn solution patterns.

What should I avoid putting into Anki for physics and math?

Avoid decks that are mostly “name → formula” trivia, and avoid long prompts that turn reviews into mini study sessions. If a card doesn’t map to what you do on problems (choose a principle, check conditions, model, compute, interpret), it tends to become busywork.

How many new cards should I add per day?

Small is sustainable. Many students do better with 3–10 high-quality new cards/day per course than 30 low-quality ones, because the real learning still needs problem solving and worked-example self-explanation.

Should I use cloze deletion?

Yes, especially for conditions (“only when …”) and key relationships. Cloze works best when it forces a specific recall, not when it hides half a paragraph.

How This Fits in Unisium

If you like spaced repetition but don’t want to hand-design everything, Unisium provides structure around the same ideas: what to study when, which principles are weak, and how retrieval, self-explanation, and problem solving fit inside one session. Ready to try it? Start learning with Unisium or explore the full framework in Masterful Learning.

Related Guides

- Retrieval Practice – Why pulling information out of your head works.

- Elaborative Encoding – How to connect ideas to make them stick.

- Self-Explanation – The strategy that turns examples into skills.

- Problem Solving – How to train the skills Anki is supporting.

- How to Study with AI – Using LLMs as a tutor, not a solver.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →