Is Zettelkasten effective for learning math and physics? The efficiency verdict

The Zettelkasten method is often useful for researchers and writers generating new theories, but usually inefficient for students mastering math and physics curricula. The method prioritizes connecting ideas over retrieving them, which can lead to a “collector’s fallacy” where you possess the notes but not the fluency. For technical subjects, active problem-solving and concept mapping usually yield better results per hour invested.

On this page

- What is the Zettelkasten method?

- The mechanism: Why it works (and when it doesn’t)

- The verdict for math and physics

- How to make it effective (The non-gimmick way)

- Start now: The 5-minute audit

- Better alternatives for students

- How this fits in Unisium

- FAQ

What is the Zettelkasten method?

The Zettelkasten (German for “slip-box”) is a knowledge management system popularized by sociologist Niklas Luhmann. Instead of organizing notes into rigid folders, you create “atomic” notes—single ideas on small cards—and link them together like a neural network.

The core promise is that by linking ideas, you create a conversation partner. The system surprises you with connections you didn’t explicitly look for. This is powerful for writing essays or developing novel theories.

However, learning math and physics requires a different cognitive operation: mastery of prerequisite-heavy models. You aren’t just trying to link “Force” to “Philosophy”; you are trying to apply to a specific constraint in a problem under time pressure.

The mechanism: Why it works (and when it doesn’t)

Zettelkasten can trigger Elaborative Encoding when your notes and links force you to explain relationships in your own words. If your workflow is mostly clipping, tagging, and browsing, you get organization without durable learning. The learning comes from the thinking you’re forced to do, not from the slip-box structure.

The missing pieces

For math and physics, the standard Zettelkasten workflow misses two critical mechanisms. Without them, the slip-box becomes a reference library rather than a training loop.

- Retrieval Practice: Browsing your slip-box is recognition, not recall. Seeing a note and nodding is not the same as being able to produce the formula from scratch. Unless you design the system to hide answers, it doesn’t train Retrieval Practice.

- Spacing: Zettelkasten has no built-in schedule. You might write a note on “Angular Momentum” and never see it again until you stumble upon it months later. Without Spacing, the memory decays.

Zettelkasten doesn’t include pretesting or posttesting, but you can store them in it. Write prediction questions before studying, then answer them later without opening the note—ideally by solving a short example. Linking topics also isn’t interleaving unless you practice choosing between competing methods; the slip-box can store “why method A, not method B” prompts, but only mixed problem sets train the decision.

The Collector’s Fallacy

It is easy to feel productive while building a Zettelkasten. You have thousands of beautiful, linked notes. But having the note is not the same as knowing the physics. This is the “Collector’s Fallacy”: confusing the possession of information with the acquisition of knowledge.

The verdict for math and physics

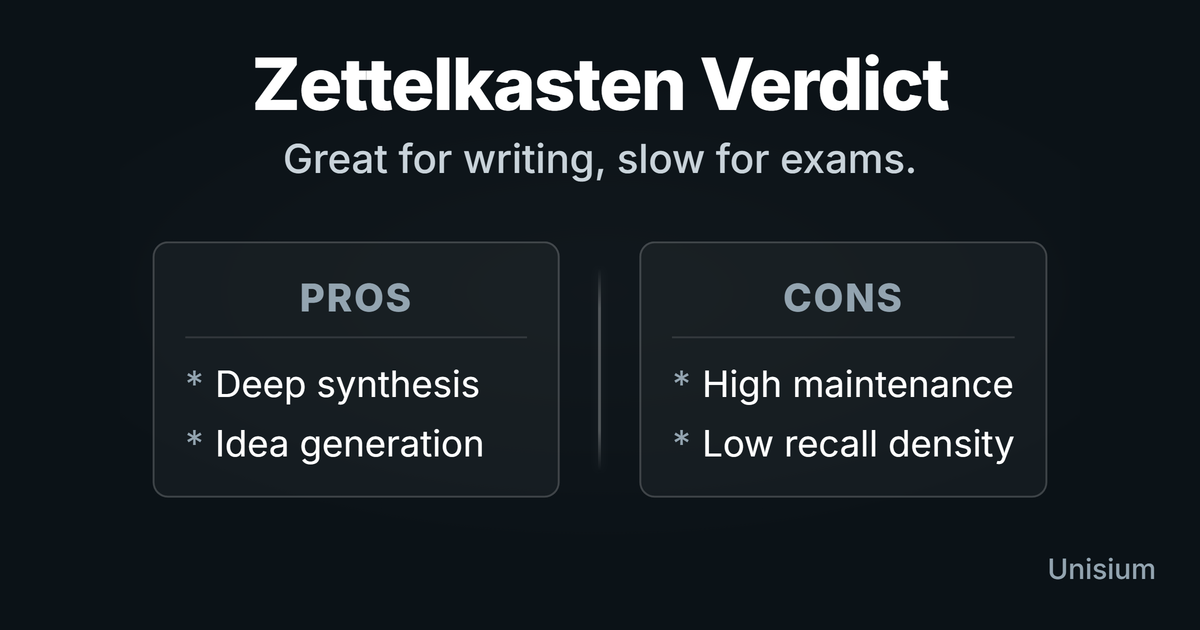

Is it effective? It depends entirely on your goal. For most students, the overhead only pays if it forces retrieval and spaced review.

When to use it (The Green Zone)

- PhD Research: You are at the frontier, trying to connect disparate fields (e.g., “Fluid dynamics in biological systems”).

- Writing a Thesis: Your output is a document, not an exam score. The Zettelkasten helps organize arguments.

- Deep Synthesis: You want to understand why concepts rhyme across domains (e.g., “How is potential energy in gravity like voltage in circuits?”).

When to skip it (The Red Zone)

- Exam Prep: If you need to solve problems quickly, Zettelkasten is negative ROI. It steals time from practice.

- Standard Curriculum: If you are learning established models (Calculus I, Mechanics), the connections are already known. You don’t need to “discover” that derivatives relate to integrals; you need to practice applying the Fundamental Theorem.

- Fluency Building: A slip-box does not help you recognize which integration technique to use under time pressure; only Interleaving practice does.

If you love Zettelkasten, keep it small and make it test you. If you don’t love it, don’t touch it—math and physics reward practice, not curation.

How to make it effective (The non-gimmick way)

If you enjoy the method and want to use it for physics, you must strip away the “productivity cosplay” and focus on learning payloads. A system that looks beautiful but doesn’t force you to think is just a distraction from the actual work of problem solving.

Rule 1: Notes are outputs, not inputs

Never write a note just to “capture” a lecture. Only write a note after you have solved a problem or explained a concept to yourself. The note is the trophy of your mental effort, not the start of it.

Rule 2: High-ROI payloads only

Don’t store definitions. Store decision-making tools:

- Condition Triggers: “Use Conservation of Momentum when external forces are zero.”

- Discriminations: “Why use Energy here instead of Kinematics? (Because time is not asked for).”

- Error Archetypes: “I forgot to square the radius. Here is the cue I missed.”

Rule 3: Enforce retrieval

Write the note title as a question (e.g., “What are the 3 conditions for Continuity?”). Do not open the note until you have answered it. If you can’t answer it, you don’t know it—even if you “have” the note.

Start now: The 5-minute audit

You can test if your current notes are working in 5 minutes. The goal is to measure retrieval and application, not how “organized” the archive feels.

- Open your note system (Zettelkasten, notebook, or app).

- Pick a concept you wrote down 2 weeks ago.

- Without reading the note, explain the concept aloud and solve a simple example.

If you can’t do it, your system is a library, not a learning tool. To fix this today, take that one note and rewrite the title as a specific question. Put a reminder in your calendar to answer that question tomorrow. You have just turned a static archive into a spaced retrieval system.

Comparison

- Up: Note-Taking During Lectures

- Zettelkasten is a post-processing activity (synthesis), not for live capture.

- Sideways: Progressive Summarization

- Progressive Summarization shrinks text (reference); Zettelkasten connects ideas (insight). Use Zettelkasten for research.

- Out: Problem Solving

- Don’t just link ideas—apply them. Problem solving builds the fluency Zettelkasten lacks.

Better alternatives for students

If your goal is efficiency, swap the slip-box for these tools. Each one pushes you toward retrieval or decision-making under constraints.

- Concept Maps: Unlike the loose web of a Zettelkasten, Mind Maps vs Concept Maps allow you to label relationships explicitly. You can see exactly how “Energy” relates to “Work” and “Force” without hiding the logic.

- Problem Logs: Instead of cataloging definitions, catalog your mistakes. A database of “Problems I missed and why” is the highest-ROI document a physics student can build. See Problem Solving.

- Flashcards (Anki): If you want to retain the atomic facts, use spaced repetition. A Zettelkasten stores the fact; Anki forces you to retrieve it.

How this fits in Unisium

The Unisium Study System adopts the “graph” idea behind Zettelkasten, but it optimizes the part students usually miss: retrieval plus scheduling. You don’t get rewarded for building a library—you get rewarded for being able to produce the idea under constraints.

We structure knowledge into a dependency graph (concepts linked to prerequisites), but we don’t ask you to build it from scratch. We provide the map. Your job is to traverse it.

Instead of spending weeks setting up a note-taking system, you spend that time on active recall. We use the graph to determine what you should study next, ensuring you never tackle a concept (like “Flux”) before you’ve mastered its parents (like “Dot Product”).

If you want a retrieval-first workflow that handles the scheduling for you, see Masterful Learning. The main idea is the same: retrieval beats curation.

FAQ

Can I use Zettelkasten for formulas?

You can, but it’s inefficient. A formula sheet or a flashcard deck is better. Zettelkasten is for ideas and arguments, not static reference data.

Is Obsidian good for math?

Obsidian is a great software tool that supports Zettelkasten (and LaTeX for math). It is excellent for Cornell Notes or general class notes. Just be careful not to over-engineer the linking system.

Doesn’t writing things down help me learn?

Yes, but the benefit comes from the processing, not the filing. Rewriting Notes is often a passive trap. Writing a self-explanation of a complex theorem is high-value; spending 20 minutes tagging it is low-value.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →