Is Progressive Summarization Effective for Learning Math & Physics? Rarely

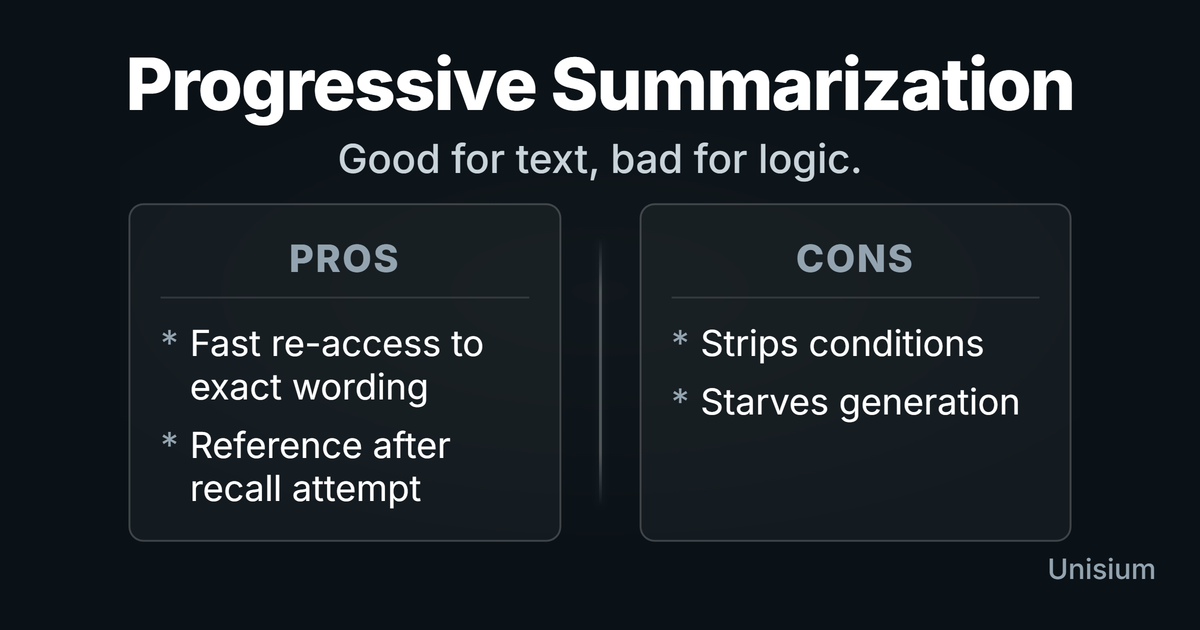

Progressive summarization layers highlights to make notes fast to re-open later. For math and physics it usually fails because it trains recognition and strips the conditions that make steps valid. If you insist on using it, convert every highlight into a retrieval prompt or a “continue-the-derivation” checkpoint.

On this page: The Core Mismatch · The Verdict · Mechanism Analysis · How to Salvage It · Unisium Approach · FAQ

What is Progressive Summarization?

Progressive summarization is a method for managing information overload by compressing notes in multiple “passes.” You start with raw text (Layer 1), bold the key phrases (Layer 2), highlight the best of the bolded sections (Layer 3), and finally write a mini-summary at the top (Layer 4). The goal is fast re-access: ensuring you can glance at a note months later and instantly grasp the main point without rereading the whole text.

The Core Mismatch: Compression vs. Reconstruction

This technique relies on compression. In math and physics, notes only help if they increase future reconstruction attempts, so progressive summarization helps mostly when it becomes a prompt generator rather than a compression workflow. You strip away “noise” to reveal the “signal,” which works well when the signal is a set of independent facts or a core thesis. However, math and physics require reconstruction. In a derivation, the “noise” (intermediate steps, conditions, assumptions) is often where the logic lives.

For technical subjects, progressive summarization suffers from two specific failure modes:

1. Condition Loss

Math and physics principles are fragile; they only work when specific conditions are met (e.g., “constant acceleration” or “closed system”). When you compress a text, these constraints often look like fluff and get stripped away. You end up with a clean formula () but lose the critical context of when it applies, leading to errors on complex problems.

2. Generator Starvation

Skill in physics comes from looking at a problem state and generating the next step. Progressive summarization trains you to recognize the next step when you see it in your notes. These are different cognitive muscles. You can be skilled at summarizing a textbook chapter—creating a beautiful, searchable artifact—while remaining completely unable to solve a problem from a blank page.

The Verdict

Is progressive summarization effective for learning math and physics? Rarely, unless you heavily modify it to force reconstruction and condition checking.

The Illusion of Competence

The biggest risk is that highlighting feels like work. It produces a visible result (a layered note) and gives you a sense of familiarity with the text. But this is often an illusion of competence. You are interacting with the typography, not the underlying logic.

Where It Can Work

There are a few narrow cases where this method is legitimate, because the goal is fast re-access rather than step generation. Even then, it only helps if you preserve conditions and constraints instead of compressing them away.

Works for constraints checklists and decision rules: This can work for items that you genuinely need as a reference, like a definition plus its required conditions. Make the final layer include “when it applies” and “what breaks if it doesn’t,” or you’re just storing landmines.

Method Selection Rules: This can work for decision cues like “use substitution when…” or “choose Gauss’s law when…”. The value is discrimination, so add at least one counterexample showing when the same cue would mislead you.

Conditions Ledger: This can work as a compact checklist of assumptions, units, and non-obvious limitations for formulas and theorems. Treat it as a reference you consult after attempting recall, not as the thing you study instead of solving.

Mechanism Analysis

Progressive summarization rarely triggers the mechanisms that drive learning unless you redesign the layers to force generation. Here is how it maps to elaboration, retrieval, testing, spacing, and interleaving.

Elaborative Encoding

Mostly No. Highlighting and bolding are perceptual selections, not elaborations. To trigger Elaborative Encoding, you must generate meaning. Unless your layers include generated questions (“Why is this step legal?”, “What happens if mass is zero?”), you are just decorating the page.

Retrieval Practice

No (by default). Standard progressive summarization is a review method, not a test. However, you can force it to be Retrieval Practice by turning Layer 4 into a test. Instead of a summary, write a prompt: “Derive the wave equation from Maxwell’s equations.” If the note doesn’t demand recall, it’s just rereading.

Pretesting and Posttesting

Not inherent. The method does not prescribe testing, but you can add it.

- Pretesting: Before touching your layers, do a 2–3 minute blank recall attempt. Your highlights must then answer specifically what you failed to generate.

- Posttesting: After Layer 4, close the note and reconstruct the derivation outline, proof skeleton, or 1–2 representative problems from memory.

Spacing and Interleaving

Not inherent. Progressive summarization doesn’t create Spacing or Interleaving unless you deliberately schedule passes and add comparison prompts. If you do all layers in one sitting, it’s just massed practice. Interleaving requires you to specifically create comparison layers (e.g., “Compare Gauss’s Law vs. Coulomb’s Law”).

How to Salvage It (The “Less Wrong” Way)

If you love this workflow and want to use it for math and physics, you must change the rules to avoid the pitfalls above. If you won’t enforce these changes, skip the method and spend the time on retrieval and problems.

1. Ban Passive Layers

No layer should be just highlighting. Every pass must add a generated element. If you highlight a formula, write a margin note asking, “What are the 3 conditions for this?” or “What units are required?” Use Self-Explanation prompts like:

- “Explain why this step is legal.”

- “What would make this step illegal?”

- “What is the goal of this transformation?“

2. Turn Layer 4 into a Test

Don’t write an executive summary. Write a retrieval checklist:

- 3 conceptual questions (Why? How?)

- 1 “continue-the-derivation” checkpoint (hide the middle steps)

- 1 “conditions list” (explicitly stated)

3. Post-Solution Autopsy Notes

Instead of summarizing the textbook, summarize your problem-solving process. After solving a hard problem, write a note about the “autopsy”: what condition did you miss? What key insight made the solution possible? This is high-value, personal knowledge that is worth distilling.

4. Time-Cap It

Processing notes is seductive because it feels productive but carries no risk of failure. Cap this activity at 10-15% of your study time. The rest should be spent on active Problem Solving.

How This Fits in Unisium

The Unisium Study System prioritizes reconstruction over reference. We believe that notes are only useful if they increase your future attempts to retrieve information from your own brain.

- Conditions, Not Just Facts: We emphasize the constraints and conditions of every principle, preventing “Condition Loss.”

- Active Application: We force you to apply concepts to problems, preventing “Generator Starvation.”

If you want to move beyond curating text and start building a solver’s mind, check out Masterful Learning.

Comparison

- Up: Note-Taking During Lectures

- Progressive Summarization is a review tool, not a capture tool.

- Sideways: Zettelkasten

- Zettelkasten expands ideas (synthesis); Progressive Summarization shrinks them (compression). Use Zettelkasten for writing.

- Out: Equation Sheets

- If you want a compressed reference, build a proper equation sheet with conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is this the same as Zettelkasten?

No. Zettelkasten is about linking ideas to create new insights, while progressive summarization is about distilling ideas for retrieval. Zettelkasten is generally better for the interconnected nature of math, provided you focus on linking principles. See Zettelkasten for Math and Physics.

Can I use it for formula sheets?

You can use the spirit of it to refine your Equation Sheets, but be careful. A “summarized” formula often lacks the necessary warnings. Ensure your final layer includes the conditions (e.g., “valid only for constant acceleration”), not just the variables.

What if I use it just for the first read?

That is acceptable as a way to stay engaged with dense text. Just recognize that “processing the notes” is not studying. Studying begins when you close the notes and try to solve a problem or derive a proof from memory.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →