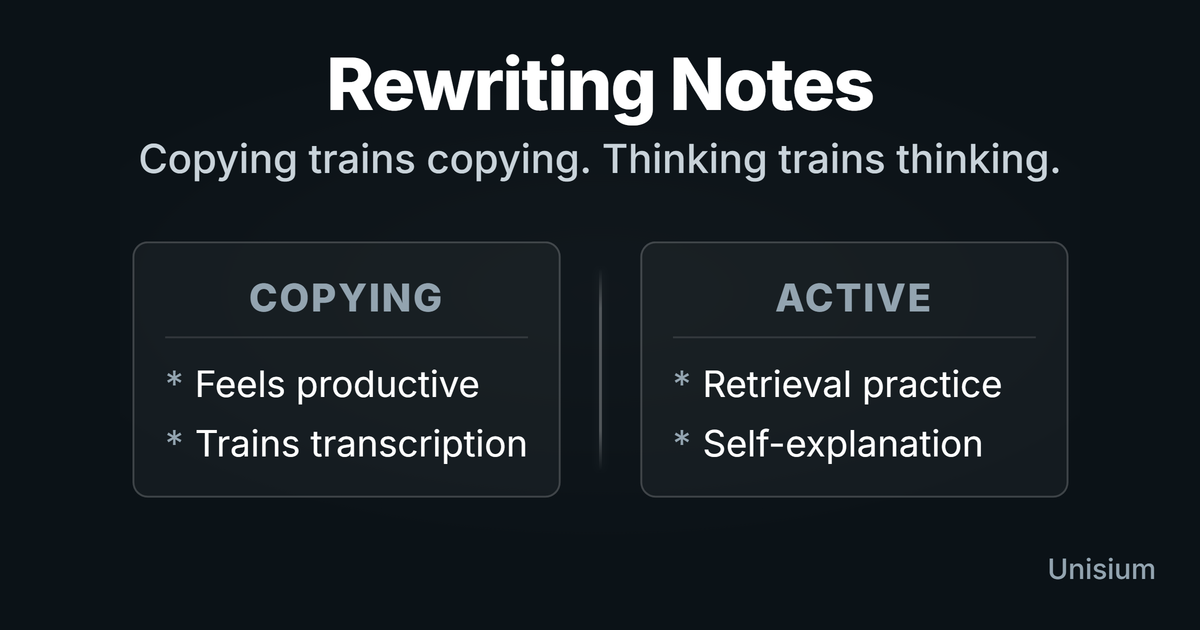

Is Rewriting Notes Effective for Learning Math & Physics? No

Rewriting notes is one of the least effective study strategies for math and physics. Pure transcription—copying your class notes into a neater format—trains transcription, not understanding. You practice moving words from one page to another while the cognitive work that builds problem-solving skill sits untouched.

Replace note-copying with retrieval practice, self-explanation, and deliberate problem solving. These strategies force active output and productive struggle plus feedback—the conditions that build durable learning. See Ineffective Study Techniques for more on why passive input fails.

If you spend hours producing beautiful, color-coded notebooks after each lecture, this guide will be uncomfortable. The time invested in rewriting notes is time stolen from strategies that build durable, usable knowledge. Neat notes are not evidence of learning. They are evidence of neat notes.

On this page: Why Rewriting Fails · The Illusion of Progress · What to Do Instead · Quick Comparison · FAQ · How This Fits

Why Rewriting Notes Fails

Transcription Is Not Thinking

When you copy notes, your attention is on reproducing what’s already there—formatting, layout, wording, and surface neatness. Your working memory is spent on reproduction, not on meaning.

Compare this to what exams demand: recognizing which principle applies to a novel problem, recalling that principle from memory, verifying its conditions, and executing the solution. Rewriting practices none of these skills. You rehearse reproduction and formatting while problem-solving ability stays static.

Zero Retrieval

Effective learning requires retrieving information from memory without looking. Each successful retrieval strengthens the memory and makes it faster to access under pressure. Rewriting does the opposite: the source material sits open in front of you the entire time. You never test whether you can recall the principle, state its conditions, or reproduce the derivation from memory.

This is why students who rewrite notes can recognize material on sight but freeze when the exam asks them to produce it from a blank page. Recognition is not recall. Copying reinforces recognition while starving retrieval.

Opportunity Cost

Every hour spent copying notes is an hour not spent on retrieval practice, elaborative encoding, self-explanation, or solving problems. The evidence for active strategies is strong; the evidence that post-lecture copying improves durable recall is weak.

The brutal math: if you spend two hours rewriting notes after each lecture, you could instead spend those same two hours doing targeted practice that moves the needle. The choice is not “rewriting vs. nothing”—it’s “rewriting vs. strategies that work.”

The Illusion of Progress

Rewriting notes feels productive because it produces a visible artifact. You start with messy scribbles and end with an organized document. That transformation feels like learning. It is not.

This is the fluency illusion: confusing ease of processing with depth of understanding. When you look at your rewritten notes, the material seems familiar and clear. But familiarity is not understanding. Clarity on the page is not clarity in your head.

The illusion is reinforced by effort. Rewriting takes time and concentration. Surely all that work must produce learning? No. Effort spent on the wrong task produces expertise at that wrong task. Hours of transcription produce transcription skill, not physics skill.

The test: Close your notes. Can you state the core principle from memory? Can you explain when it applies and when it doesn’t? Can you set up a problem that uses it? If not, your rewriting session taught you to copy, not to think.

Want the complete framework behind this guide? Read Masterful Learning.

What to Do Instead

Replace note-copying with active strategies that demand cognitive work matching what exams require.

1. Retrieve Before You Review

Before touching your notes, try to recall the main principles from the lecture. Write them from memory on a blank page. State the conditions for each principle. Only then open your notes to check what you missed.

This retrieval attempt—even if you fail—strengthens memory more than any amount of copying. See the full protocol in Retrieval Practice.

2. Explain the Steps

Instead of copying a derivation, cover it and try to reproduce the reasoning. For each step, ask: What principle justifies this? What conditions must hold? What is the goal of this step?

This is self-explanation. It turns passive reading into active reasoning and produces retrievable “condition → action → goal” rules you can apply to new problems.

3. Solve Problems

The highest-leverage use of post-lecture time is solving problems that require the day’s principles. This forces retrieval, exposes gaps, and builds the exact skill exams test.

If you don’t know where to start, use the Five-Step Strategy to structure your approach. The struggle of solving—not the comfort of copying—is where learning happens.

4. If You Must Take Notes, Transform Them

If you refuse to abandon notes entirely, at least transform them rather than transcribe them. Rewrite in your own words. Add questions. Create problems. Link to prior knowledge. Make the note-taking session an elaborative encoding session.

But be honest: if your notes look identical to the originals (just neater), you copied. Copying is not transformation.

Comparison

- Up: Note-Taking During Lectures

- Rewriting is just “Note-Taking Part 2.” The hub explains why transcription fails twice.

- Sideways: Aesthetic Notes

- Rewriting is about neatness; Aesthetic Notes are about beauty. Both are passive traps.

- Out: Self-Explanation

- Don’t copy the derivation—explain why each step happens.

FAQ

Is rewriting notes ever useful?

Rarely. If rewriting forces you to think about the material differently—reorganizing by concept, adding your own questions, or explaining in your own words—it can have some value. But that’s not rewriting; that’s transformation. Pure transcription (copying word-for-word or symbol-for-symbol) has no meaningful benefit. Your time is better spent on retrieval, self-explanation, or problem solving.

What if rewriting helps me remember the material?

It probably doesn’t. The feeling of remembering comes from familiarity, not durable memory. Test yourself: close your notes 24 hours after rewriting and try to recall the core principles. If you can’t, the rewriting session didn’t produce usable learning. The testing effect shows that retrieval practice beats passive review for long-term retention.

My professor said neat notes are important. Are they wrong?

Neat notes can help you find information later. But that’s organization, not learning. If you need an organized reference, create one—but don’t confuse the act of creating it with studying. The time spent organizing should be minimal. The time spent actively practicing with the material should dominate.

What about rewriting notes by hand instead of typing?

Some research suggests writing by hand involves more cognitive processing than typing. But this applies to note-taking during lectures (where paraphrasing is required), not to post-lecture copying. Copying by hand is still copying. The medium doesn’t change the fundamental problem: transcription doesn’t require understanding.

How do I break the habit of rewriting notes?

Start by tracking your time. Record how many hours you spend rewriting each week. Then reallocate half that time to retrieval practice or problem solving. Compare your exam performance before and after. The data will be convincing.

How This Fits in Unisium

The Unisium Study System is built on strategies that force active output: retrieval practice, self-explanation, elaborative encoding, and structured problem solving. These strategies demand cognitive work that matches what exams require—and they’re what Unisium drills when you practice.

Rewriting notes has no place in this system. It produces artifacts, not ability. If you’ve been a dedicated note-copier, the switch will feel uncomfortable at first. The discomfort is the point: productive struggle plus feedback builds usable skill. Comfort often builds familiarity.

Ready to replace copying with practice that works? Start learning with Unisium or explore the full framework in Masterful Learning.

Masterful Learning

The study system for physics, math, & programming that works: encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, principled problem solving, and more.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →