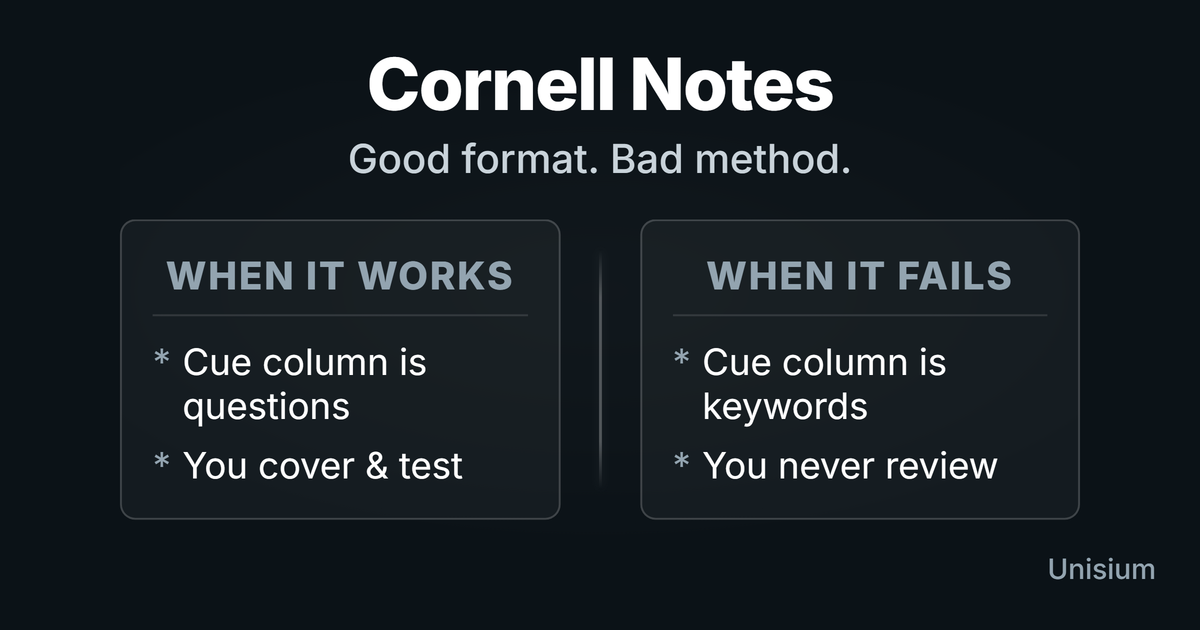

Cornell Notes: Better Than Transcription, But Not Enough

Cornell Notes are a note format with a cue column, note area, and summary box. They work only when the cue column forces retrieval from memory (without looking) and the summary forces elaboration; otherwise it’s transcription with nicer margins. Write questions on the left and elaboration prompts at the bottom so your notes become a built-in quiz.

On this page: Why It Works · Unisium-Aligned Upgrade · How To Do It · Common Mistakes · Start Now · FAQ · Comparison · How This Fits in Unisium

Why It Works

Learning comes from testing and connecting. Cornell Notes work only when they force two learning moves: retrieval and elaboration. Retrieval strengthens access to ideas because you practice reconstructing them instead of rereading them.

The cue column is useful because it gives you prompts that you can answer without looking. The summary box is useful because it forces connections and predictions through questions (elaborative encoding), which improves transfer to new problems.

Skeptical take: The Cornell layout is not a learning method. If the left column is keywords and you never cover the notes, you built a prettier archive.

Want the full framework behind the Unisium Study System? Read Masterful Learning.

The Unisium-Aligned Upgrade

The traditional Cornell method tells you to write “keywords” in the left column and a “summary” at the bottom. This is often too passive. If you want Cornell Notes to align with the Unisium approach, here’s the upgrade:

1. Keywords → Retrieval Questions Instead of writing “Newton’s Second Law” in the left column, write “When does Newton’s Second Law apply?” or “Write the equation for Newton’s Second Law.” This turns the column into a built-in quiz.

2. Summary → Elaboration Instead of listing what was covered, use the summary box to connect the new lecture to previous topics. This forces elaborative encoding. Use specific question types:

- Between-Principles: “How is this like [Topic A], and how is it different?”

- For-Principle: “What condition must be true for this to apply?”

- Within-Principle: “If [Variable] doubles, what happens to [Outcome]?”

3. Review → Retrieval Don’t reread your notes. Cover the right side (the notes) and try to answer the questions on the left. This is retrieval practice.

How to Do Cornell Notes Right

Step 1: Set Up the Page

Divide your page:

- Right Column (~6 in / ~15 cm): For taking notes during class.

- Left Column (~2.5 in / ~6 cm): For questions (The Cue Column).

- Bottom (~2 in / ~5 cm): For the summary.

Step 2: Take Notes (Intelligently)

During class, use the right column. Do NOT transcribe. Instead, capture principle names, conditions, and diagrams (see Learning Arenas). Focus on the logic, not the words. If the lecture moves too fast, stop writing and start listening—transcription crowds out the thinking that creates understanding (see Note-Taking During Lectures).

Step 3: Create Questions (Immediately After)

This is the most important step. As soon as possible after class, review your notes. In the left column, write questions that the notes on the right answer.

- Bad: “Kinetic Energy”

- Good: “How does Kinetic Energy change if velocity doubles?”

Step 4: Test Yourself

Cover the right side. Read the question on the left. Answer it aloud or in your head. Check your answer. This turns your notes into flashcards.

Common Mistakes (and the Fix)

| Mistake | Fix |

|---|---|

| Transcribing | Don’t write everything. Listen, process, then write. |

| Passive Cues | Writing “Keywords” in the left column is weak. Write full questions. |

| Skipping the Summary | The summary is your chance to elaborate. Don’t skip it. |

| Never Reviewing | Notes are useless if you don’t use them. Use the fold-over method to quiz yourself. |

Start Now (5 minutes)

Have a page of notes from today?

- Draw a line down the left side (if you didn’t already).

- Read a paragraph of your notes.

- Write a question in the left margin that tests that paragraph.

- Cover the notes and answer the question.

FAQ

Is this better than flashcards?

It’s a good source for flashcards. Cornell Notes keep the context (the lecture flow), while flashcards isolate the facts. Use Cornell Notes for the first pass, then move hard items to spaced repetition systems.

Can I type them?

Yes. Handwriting is not magic. What matters is whether you paraphrase and then use the cue column for retrieval from memory (without looking). If typing makes you transcribe, you lose the benefit—so slow down, summarize, and quiz yourself.

What if the professor talks too fast?

Stop writing. Prioritize listening and understanding the logic. Jot down questions or confusion points, but don’t try to capture the transcript. Fill in the notes later from the textbook.

If a concept still won’t stick, do a 3-minute teach-back: explain it in plain language from memory, then check the source and fix what you got wrong. That’s elaboration/self-explanation—not a new method.

Comparison

- Up: Note-Taking During Lectures

- Cornell is one of the better paper formats, but the hub explains why active listening often beats writing.

- Sideways: Outline Method

- Outlines organize information. Cornell makes retrieval easier if you write questions.

- Out: Retrieval Practice

- The “Cue Column” is just a retrieval practice tool. Use it to test yourself.

How This Fits in Unisium

Cornell Notes become useful when they run the two loops Unisium is built on: retrieval practice (cue column) and elaborative encoding (summary prompts). That avoids passive rereading, one of the most ineffective study techniques.

If you prefer visual organization, convert your Cornell summaries into concept maps with labeled links. Concept maps are just elaborative encoding in diagram form—the learning happens in the relationships (the “why/how” labels), not the boxes.

Use a Pomodoro block to make the post-lecture review happen reliably.

Ready to use it? Start learning with Unisium at app.unisium.io or read Masterful Learning.

Masterful Learning

The study system for physics, math, & programming that works: encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, principled problem solving, and more.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →