Is Rereading Effective for Learning Math & Physics? Rarely

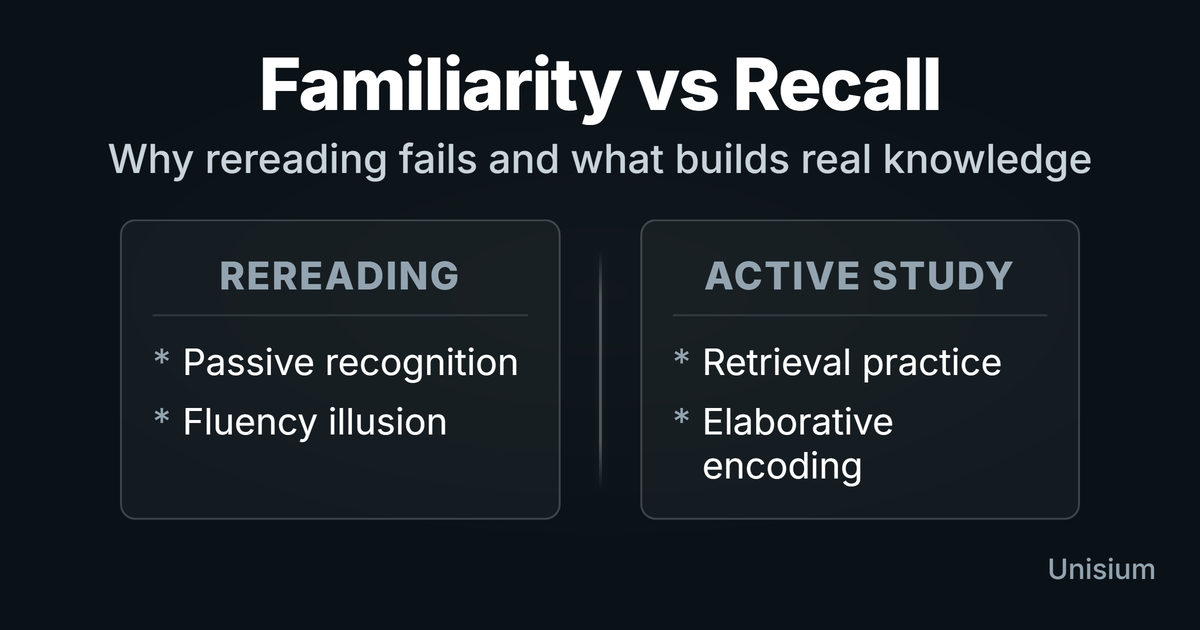

Rereading is a poor main strategy for math and physics because it boosts recognition without strengthening retrieval or application. You can feel fluent while still being unable to recall key principles from memory, check their conditions, or set up a novel problem. Use rereading only as a quick orientation, then switch to retrieval practice, self-explanation, and spaced problem solving for durable performance.

Rereading dominates because it feels productive: the material becomes familiar and easier to process. That ease is recognition, not recall. Math and physics exams reward retrieving principles and applying them to new structures under time pressure. If you keep rereading, you rehearse sentences instead of building a usable model.

Familiarity is not understanding. Recognition is not recall.

When you reread, you’re training your brain to recognize sentences you’ve seen before. Exams don’t reward this. They ask you to recognize problem structures, retrieve principles from memory, and apply them to novel situations. Rereading practices none of that.

On this page: Why Rereading Fails · The Fluency Illusion · What to Do Instead · Quick Comparison · FAQ · How This Fits

Why Rereading Fails for Math and Physics

1) It’s Passive Input, Not Active Output

When you reread a derivation of the work-energy theorem, you’re consuming information. Your eyes move across the page. You nod along. But you’re not doing the thing that builds skill: generating the knowledge from memory, explaining why each step follows from the previous one, or testing your ability to apply it.

Exams are output tests. Rereading practices input. The mismatch is fundamental.

2) It Doesn’t Build Retrieval Strength

Memory has two components: storage strength (how well something is encoded) and retrieval strength (how easily you can access it). Rereading might slightly increase storage strength, but it does nothing for retrieval strength. That’s why you can reread a chapter three times, feel confident, and then blank on the exam.

Retrieval practice builds retrieval strength. Rereading doesn’t.

3) You Skip the Hard Parts

When rereading, your attention naturally drifts to what you already understand. The confusing parts—where you’d need to slow down and think—get skimmed. This is comfortable. It’s also counterproductive. The confusing parts are precisely where you need to do work.

Active strategies force you to confront gaps. Rereading lets you avoid them.

4) It Doesn’t Match Exam Conditions

On a physics exam, you’re given a novel problem. You must recognize what type of problem it is, retrieve the relevant principles, check their conditions, and execute a solution—all from memory, under time pressure. Rereading practices none of these skills.

Principle of specificity: You learn what you practice. Rereading practices recognizing text. Exams require recognizing structures and generating solutions.

The Fluency Illusion

Rereading creates a dangerous sense of competence called the fluency illusion. Material feels easier on the second and third pass—not because you understand it, but because you recognize it. Your brain confuses “I’ve seen this” with “I know this.”

People often overestimate preparedness after rereading because familiarity inflates confidence.

The fix isn’t to read harder. It’s to test yourself. When you attempt retrieval and fail, you get accurate feedback about what you don’t know. When you reread and feel fluent, you get false feedback. For more on why this happens, see the research overview in Masterful Learning.

Skeptical take: Rereading feels like studying. But effort and learning are decoupled. What feels easy often doesn’t stick. What feels difficult—retrieval, self-explanation, solving problems—is what builds durable knowledge.

Want the complete framework behind this guide? Read Masterful Learning.

Can Rereading Be Salvaged?

Rarely. Rereading is inherently passive. However, if you must reread, you can make it slightly less ineffective by turning it into Pre-questioning:

- Scan headings first. Turn them into questions (e.g., “What are the conditions for Conservation of Momentum?”).

- Read to answer. Read the text specifically to find the answer to your question.

- Close and verify. Look away and answer the question.

This forces a small amount of retrieval. But generally, you are better off switching to Retrieval Practice immediately. This is similar to the failure mode of Summarizing—both can feel productive while bypassing the hard work of recall.

What to Do Instead

The time you’d spend rereading is better spent on strategies that force active processing. Here’s how to redirect that time:

Use this replacement loop:

- Skim once for orientation (2-3 minutes).

- Close notes and write what you can recall (principle, conditions, typical cues).

- Check, then self-explain one worked step you missed.

- Solve 1-2 short problems that force the same principle under a new surface form.

Then schedule the next touch on a short interval and stretch it over time. That’s spacing applied to retrieval and problem solving, not spaced rereading. If your course has near-neighbor topics that people mix up, add interleaving so you practice selecting the right principle.

Replace Rereading with Retrieval Practice

Instead of rereading the section on Newton’s second law, close the book and try to recall: What does the law state? What’s the equation? When does it apply? What are the conditions?

Then check yourself. Three successful retrievals with spacing beats ten rereadings. See: Retrieval Practice.

Replace Rereading with Self-Explanation

Instead of rereading a worked example, cover the solution and explain why each step follows from the previous one. Ask yourself: What principle justifies this step? What would happen if I changed this variable?

This bridges understanding to application. See: Self-Explanation.

Replace Rereading with Elaborative Encoding

Instead of rereading a concept, answer three questions:

- What does this mean? Define it in your own words.

- When does it apply? What conditions must hold?

- How is it different from related concepts?

This builds the connections that enable recall. See: Elaborative Encoding.

When Rereading Might (Narrowly) Help

Rereading isn’t useless in all contexts. It has narrow valid uses:

Initial confusion. If a passage is genuinely unclear on first read, a second pass helps you build basic comprehension. But stop at two reads. If it’s still unclear, switch to self-explanation or ask for help.

Finding specific information. If you’re looking up a formula or checking a definition, rereading is fine. This is reference lookup, not studying.

Before active practice. A quick skim before retrieval practice can prime your memory. But the skim isn’t the study—the retrieval is.

Avoid “spaced rereading” as your plan. Spacing works when you space retrieval and elaboration, because you have to generate meaning and decisions from memory.

Signal: If you’re on your third or fourth reread of the same section, you’re using the wrong strategy. Switch to active methods.

Quick Comparison: Rereading vs. Effective Alternatives

| Goal | Rereading | Effective Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Understand meaning | Weak (passive exposure) | Strong: Elaborative Encoding questions |

| Build retrieval strength | None | Strong: Retrieval Practice with spacing |

| Know when principles apply | None | Strong: Condition-checking during self-explanation |

| Solve new problems | None | Strong: Problem Solving + Five-Step Strategy |

| Calibrate confidence | Harmful (fluency illusion) | Strong: Retrieval feedback reveals gaps |

FAQ

Is rereading ever useful for studying?

Rarely. A second pass on genuinely confusing material can help build basic comprehension. Beyond that, the time is better spent on retrieval, self-explanation, or problem-solving. Rereading beyond two passes has minimal returns.

How many times should I read something before studying differently?

Once or twice, then switch. Read once for comprehension. If it’s still unclear, read again more carefully. Then close the book and test yourself. The retrieval—not the rereading—is what builds durable knowledge.

What if I don’t feel ready to test myself yet?

Test anyway. The discomfort of failed retrieval is informative—it shows you exactly what you don’t know. The comfort of rereading is misleading—it makes you think you know more than you do. See pretesting for why testing before you feel ready works.

Why does rereading feel so productive if it doesn’t work?

Fluency illusion. Familiar material feels easier, and your brain interprets “easy” as “understood.” But ease of processing isn’t the same as depth of encoding. What feels smooth while studying often fails under exam pressure.

What’s the difference between rereading and review?

Review is active; rereading is passive. Effective review involves testing yourself, explaining concepts, or solving problems. Rereading is just re-exposing yourself to text. The distinction matters because your brain learns from what you do, not what you see.

How This Fits in Unisium

The Unisium Study System replaces rereading with active strategies: you retrieve principle names, forms, and conditions from memory; you self-explain why worked example steps follow from principles; you solve novel problems that force application. Every session emphasizes output over input, building the retrieval strength that rereading fails to develop.

Ready to try it? Start learning with Unisium or explore the full framework in Masterful Learning.

Next Steps

- Do instead: Retrieval Practice

- Big picture: Ineffective Study Techniques

Masterful Learning

The study system for physics, math, & programming that works: encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, principled problem solving, and more.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →