Is study music effective for learning math and physics? Only sometimes

For complex math and physics, silence or steady noise beats music because lyrics and changing melodies compete with the inner speech and working memory you need for equations and logic, slowing you down and raising error rates. Use music only as a starter (first 10 minutes) or during rote tasks, then cut it for the hard parts so you keep full capacity and avoid becoming dependent on one setup.

Start Now (5 minutes)

Use this 3-step micro-protocol to test your focus right now. Treat it as an experiment, not a belief.

- Pick one problem set or derivation you need to finish.

- Start with instrumental music or white noise to get over the initial resistance. This is the same startup resistance described in The Initial Struggle.

- The Cut Rule: The moment you get stuck or need to hold multiple variables in your head, cut the audio. If you feel a noticeable clarity, that’s a strong signal the audio was costing you.

The mechanism: Dual-task interference

Learning math and physics requires heavy use of your working memory. You need to hold variables, visualize geometric relationships, and manipulate logic simultaneously. This cognitive workspace is limited.

The “irrelevant sound effect” occurs when background noise interferes with this processing. The interference is strongest when the noise contains speech. Your brain’s phonological loop—the inner voice you use to read and solve problems—automatically tries to process lyrics, even if you ignore them.

This is dual-task interference. When you listen to lyrical music while solving a differential equation, you are forcing your brain to multitask. This split attention reduces your processing speed and increases the error rate. The cost is not just distraction; it is a reduction in the available “RAM” for the physics problem at hand.

The hidden trap: Over-reliance on one soundtrack

Context cues can influence recall, but music is usually only one cue among many (desk, lighting, time of day, stress). Most students will not lose exam performance just because the playlist is missing.

The real risk is narrower: if you only do hard problems with the same audio, silence can feel unfamiliar and your focus routine can wobble. If your focus only works with one soundtrack, you’ve built a brittle cue—see how to diversify cues in Study Habits. The fix is small—do some deep-work blocks without music (or cut audio for the last 20–30 minutes) so your problem-solving skill is not tied to one setup.

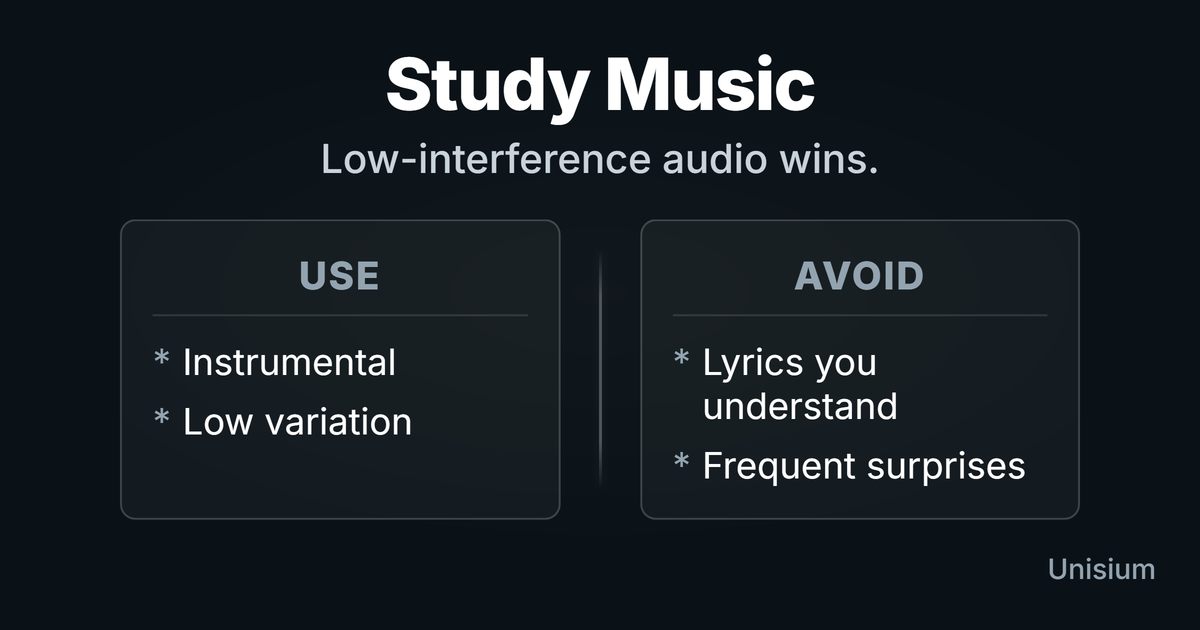

The verdict: Sound profiles

Not all sound environments are equal. For deep learning tasks, some sound profiles are reliably lower-interference than others:

Sound profiles that work

- Silence: The gold standard for high-load tasks like learning a new theorem or solving a novel problem. It imposes zero external load.

- Continuous Noise: White noise, pink noise, or rain sounds. These mask distracting transient noises (like a conversation nearby) without engaging the language centers.

- Instrumental, Low-Variation Music: Long-form ambient or drone music. It provides a steady texture without “events” (drops, solos, vocal chops) that grab attention.

Sound profiles that hurt

- Lyrical Music: The worst option for deep work. The lyrics compete directly with the verbal and semantic processing required for study.

- High-Variation Music: Genres with frequent dynamic changes, drops, or complex melodies. Every surprise is a micro-interruption to your train of thought.

Personal note: My default is long, low-variation instrumental or ambient music because it fades into the background. If I notice I’m “listening” to the track, it’s too attention-grabby for hard problems. A track that often works for me is Koan – “Fern Thicket”.

Heuristic: The “Flow + No Penalty” rule

If a track reliably helps you enter flow, that matters. Flow increases time-on-task and reduces friction, which can beat “perfect” study conditions you don’t stick with.

Use a simple two-signal check. Keep the music if it (a) helps you stay absorbed, and (b) does not noticeably raise errors or slow you down on the same kind of work.

- Flow signal: You work 20–40 minutes without checking your phone, skipping steps, or feeling pulled away.

- Penalty signal: You catch yourself re-reading lines, losing your place in derivations, or making more sign/algebra slips than usual.

Rule: If Flow is high and Penalty is low, the music is “safe enough.” If Penalty is high, keep the music for warm-up/rote work and cut it for the hard parts. Treat this as a decision rule, not an identity statement—more examples of useful defaults in Effective Study Mindsets.

Protocol: The Fade-to-Silence method

To balance the mood benefits of music with the cognitive benefits of silence, use this three-step protocol for your next physics or calculus session. If you like structure, pair it with a timer ramp (Pomodoro as starter motor).

1. The mood boost (0–10 minutes)

Start your session with your favorite high-energy music. It doesn’t matter if it has lyrics. The goal here is to organize your desk, open your notes, and get over the initial resistance. Do not start difficult problems yet.

2. The transition (10–15 minutes)

Switch to instrumental music or a familiar lo-fi playlist. Begin your warm-up problems. These should be easier tasks that don’t require your full cognitive capacity, like reviewing flashcards or copying diagrams.

3. The deep work (15+ minutes)

As soon as you encounter a difficult problem or need to learn a new concept, pause the music. Switch to silence or steady white noise. Your brain is now warmed up, and you need 100% of your working memory for the task.

How this fits in Unisium

The Unisium Study System leans on high-effort activities like active recall and step-by-step problem solving, where working memory is often the bottleneck. If music helps you show up and stay consistent, keep it—consistency beats perfect conditions.

For the hardest cards, prefer silence, steady noise, or low-variation instrumental tracks, and apply the Cut Rule when you hit a real sticking point. If you want a deeper framework for choosing methods and environments, see Masterful Learning and pair this with retrieval practice.

FAQ

What about the Mozart Effect?

The “Mozart Effect”—the idea that listening to classical music makes you smarter—is largely a myth. Studies show that any temporary performance boost is due to the mood elevation described above, not the music itself. You would get a similar benefit from any audio you enjoy, provided it doesn’t distract you.

Do binaural beats work?

The evidence for binaural beats enhancing concentration is weak and inconsistent. While some users report feeling more focused, this is likely a placebo effect or simply the benefit of masking background noise. If they work for you as a form of white noise, use them, but don’t expect them to alter your brain waves significantly.

Can I listen to music for rote tasks?

Yes. If you are formatting a bibliography, cleaning up your aesthetic notes, or organizing files, music is fine. These tasks have low cognitive load, so the interference is negligible. Save the silence for the hard math.

Next Steps

- Can’t start? See Study Habits or Pomodoro Technique.

- Start but drift? See From Resistance to Flow.

- Working but not improving? See Effective Study Mindsets.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →