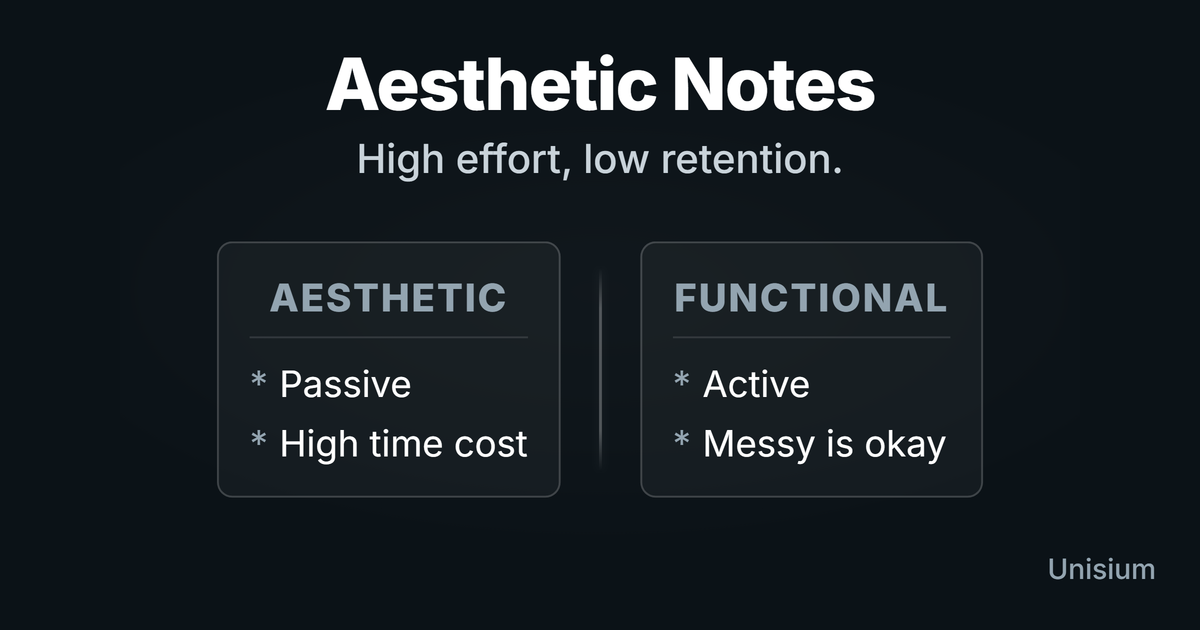

Is Aesthetic Note-Taking Effective for Math and Physics? Low ROI

Aesthetic notes are visually polished summaries that prioritize layout and color over content. While they feel productive, they are generally ineffective for math and physics because they increase extraneous cognitive load and create a “fluency illusion” where neatness masks a lack of understanding. In the Unisium Study System, we recommend replacing them with functional, messy notes that force active retrieval and elaboration.

On this page: The Trap of Beauty · The Verdict · How to Make It Work · Start Now · FAQ

The Trap of Beauty

In the age of “StudyGram,” it is easy to believe that beautiful notes equal beautiful learning. The logic seems sound: if you care enough to make it look good, you must be engaging deeply with the material. However, for technical subjects like math and physics, this intuition is often wrong because it optimizes for a pleasing artifact rather than a prepared mind.

The Cognitive Load Problem

Learning requires working memory. When you solve a physics problem or derive a math proof, your working memory is juggling variables, principles, and logical steps. If you are also worrying about color palettes, calligraphy, and layout spacing, you are adding extraneous load—mental effort that does not contribute to learning.

This is a zero-sum game. Every ounce of mental effort spent on formatting is an ounce of effort not spent on encoding. In math and physics, where understanding is built through struggle and problem-solving, this distraction predictably slows skill acquisition.

Visual structure is fine; decorative redesign loops are the problem.

The Illusion of Competence

Aesthetic notes create a dangerous fluency illusion. When you look at a perfectly formatted page of notes, it feels like you understand the material because the page is organized. But organization on paper does not guarantee organization in your brain.

You might feel like a master of the subject because you have transcribed the textbook’s content into a beautiful format. But transcription is a passive activity. Unless you are actively re-structuring the information or solving problems from memory, you are likely just moving information from one external source to another without it ever passing through your long-term memory.

The Opportunity Cost

The biggest cost of aesthetic notes is time. Creating a “Pinterest-worthy” set of notes can take hours. That is time you could have spent doing retrieval practice or solving practice problems.

In math and physics, doing is more important than viewing. You cannot learn to solve differential equations by drawing a beautiful title about them. You learn by solving them, getting stuck, and solving them again. If your note-taking method prevents you from doing practice problems, it is actively harming your grades.

The Verdict

Are aesthetic notes effective for learning math and physics? Usually no. They train recognition and presentation more than the retrieval and condition-checking required for exams. For the primary goal of mastering technical material, they often prioritize cataloging information over producing solutions under time pressure.

When They Fail

- Derivations: Real problem solving is non-linear and messy. Forcing a derivation into a rigid aesthetic structure restricts the “scratchpad” thinking needed to find the solution.

- Exam preparation: Reading over pretty notes is a passive review strategy, which is one of the least effective ways to study.

- Conditions: Aesthetic notes often prioritize the “what” (formulas) over the “when” (conditions). This leads to using the right equation in the wrong context.

When They Might Work (With Caveats)

- Cueing Systems: If you use color strictly for function (e.g., red for forces, blue for velocities), it can help chunk information.

- Reference: They can serve as a personal textbook for looking up constants or definitions, provided you don’t mistake making them for studying.

Summary: Works vs. Breaks

- Works if: You timebox formatting, use color only for conditions/traps, and end each page with closed-book prompts plus one problem plan.

- Breaks if: You redraw layouts, copy without prompts, or “review” by simply rereading the page.

How to Make It Work

If you love the aesthetic method and refuse to give it up, you must modify it to support active learning. Use these five rules to turn your notes from a time sink into a learning engine.

1. Cap the “Pretty Time”

Set a strict time limit for setup. Use a fixed template and a fixed color palette, and never redesign your system for a new topic. If it takes longer than 15 minutes to set up a page, you are procrastinating, not studying.

2. Convert Beauty into Constraints

Use visual emphasis only for meaning, not decoration. Reserve specific colors for conditions, common traps, or sign conventions. Everything else must remain plain. This forces you to think about the structure of the knowledge, not just the look of the page.

3. Force Elaboration

Don’t just copy facts; interrogate them. Every major formula or principle on your page must have a prompt next to it: “Why is this valid here?” or “What condition makes this legal?”. If you cannot answer these questions, the note is unfinished, no matter how good it looks. This drives elaborative encoding.

4. Force Retrieval

Turn your headings into questions. Instead of writing “Newton’s Second Law,” write “When does F=ma apply?”. Add a “closed-book” block at the bottom of the page with 3-5 prompts you must answer without looking. If you can’t answer them, the page is decoration, not study.

5. Serve Problem Solving

For each topic page, add one worked problem skeleton: Given Goal Principle Conditions Plan. If the page doesn’t end in a solved problem or an executable plan, it is not aligned with physics and math performance.

Comparison

- Up: Note-Taking During Lectures

- Aesthetic notes are usually done post-lecture. If you do them live, you miss the content.

- Sideways: Rewriting Notes

- Aesthetic notes add design fatigue to transcription. Rewriting is faster but still passive.

- Out: Problem Solving

- Stop drawing the problem and start solving it.

Start Now (5 Minutes)

You can test the “Functional Note” approach in your next session. If you can’t finish this in 5 minutes, you’re drifting back into craft mode.

- Grab a “trash” notebook: Use paper you don’t care about ruining.

- Pick a problem: Choose a standard problem from your current topic.

- Solve it messily: Scribble diagrams, cross out mistakes, and write down your logic in real-time.

- Review the mess: Ask yourself, “Did this messy process help me solve the problem?”

- Compare: Contrast this with your aesthetic notes. Which one moved you closer to the solution?

If you are ready to move beyond pretty notes and start mastering the material, check out our guide on Masterful Learning for a complete system.

FAQ

Can I never use colors?

You can use colors, but use them functionally. In physics, using a consistent color for specific variables (e.g., green for acceleration) can help you parse complex diagrams. This reduces cognitive load if it is sparse, consistent, and tied to meaning rather than decoration.

What if making pretty notes motivates me?

Motivation is important, but be careful not to confuse “feeling motivated” with “learning.” If pretty notes get you to the desk, that’s a start. But once you are there, try to transition to more active, less polished methods for the heavy lifting.

Should I rewrite my messy notes to make them neat later?

Generally, no. Rewriting notes is often a passive trap. If you want to consolidate your knowledge, try to summarize the key points from memory (retrieval practice) instead of copying them.

How This Fits in Unisium

The Unisium Study System prioritizes active recall and cognitive efficiency over static storage. We believe that the value of note-taking is in the process of thinking, not the product of the paper. Instead of creating a beautiful reference library, use your time to test yourself, as the act of pulling information from your brain strengthens the neural pathways needed for exams.

Effective study should feel like a mental workout, not a craft project. If your note-taking feels effortless and relaxing, you probably aren’t learning as much as you could be. Furthermore, static, perfect notes imply that knowledge is fixed, whereas rough, evolving notes reflect the reality of learning where connections are constantly being made and revised.

Masterful Learning

The study system for physics, math, & programming that works: encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, principled problem solving, and more.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →