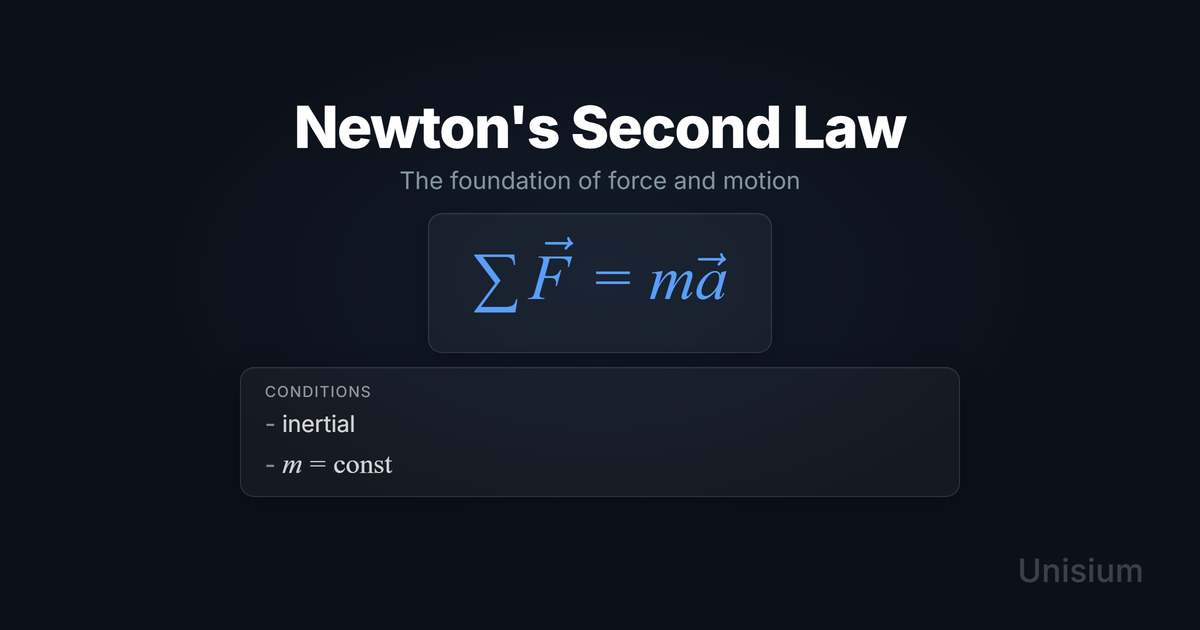

Newton's Second Law for Translation: The Foundation of Force and Motion

Newton’s Second Law for Translation states that the net force acting on an object equals the product of its mass and acceleration: the vector equation . It is the cornerstone of classical mechanics because it connects what we observe (motion) to what causes it (forces). For short interactions, you often apply it through the impulse-momentum theorem.

For short interactions, see the Impulse–Momentum Theorem.

This guide uses the Unisium Study System: elaborative encoding, retrieval practice, self-explanation, and problem solving.

On this page: The Principle · Conditions · Misconceptions · EE Questions · Retrieval Practice · Worked Example · Solve a Problem · FAQ

The Principle

Statement

Newton’s Second Law for Translation states that the vector sum of all forces acting on an object equals the product of the object’s mass and its acceleration vector. When forces are unbalanced, the object accelerates in the direction of the net force.

Mathematical Form

Where:

- = net force (vector sum of all forces acting on the object), measured in newtons (N)

- = mass of the object, measured in kilograms (kg)

- = acceleration vector of the object, measured in meters per second squared (m/s²)

Alternative Forms

In different contexts, this appears as:

- Component form: , ,

- Scalar form (one-dimensional motion):

Conditions of Applicability

Condition: inertial;

Practical modeling notes

- Subrelativistic speeds: The object’s speed must be much smaller than the speed of light (). For typical physics problems, this means speeds well below 10% of light speed—essentially all everyday motion.

- Inertial reference frame: You must be observing from a non-accelerating reference frame. The law doesn’t hold in rotating or accelerating frames without adding fictitious forces.

- Point mass or rigid body translation: The law describes translational motion. For rotating rigid bodies, you need the rotational analog (torque and angular acceleration).

When It Doesn’t Apply

- Relativistic speeds: When objects move at appreciable fractions of light speed, you must use relativistic mechanics where with relativistic momentum.

- Non-inertial frames: In an accelerating elevator or rotating platform, the law appears to fail unless you account for fictitious forces (centrifugal, Coriolis, etc.).

Want the complete framework behind this guide? Read Masterful Learning.

Common Misconceptions

Misconception 1: “If an object moves, there must be a force in the direction of motion”

The truth: Net force points in the direction of acceleration, not velocity. An object can move at constant velocity with zero net force—forces can cancel completely (see Newton’s First Law).

Why this matters: Students often draw (or invent) a “forward force” just because something is moving. The correct question is: is the velocity changing? If not, even if the object is moving.

Misconception 2: “Force causes velocity”

The truth: Force causes acceleration, not velocity. An object moving at constant velocity has zero net force (Newton’s First Law).

Why this matters: Students often write instead of , leading to completely incorrect solutions. Velocity and acceleration are fundamentally different—one is the rate of change of the other.

Misconception 3: “Mass and weight are the same thing”

The truth: Mass (, in kg) is an intrinsic property representing inertia. Weight (, in N) is a force—specifically, the gravitational force acting on that mass. Mass appears in Newton’s Second Law; weight is one possible force in the sum .

Elaborative Encoding

Use these questions to build deep understanding. (See Elaborative Encoding for the full method.)

Within the Principle (1–2)

- What does each symbol (, , ) mean physically, and what are the units on both sides of the equation?

- Why is this a vector equation? What specific error happens if you ignore direction?

For the Principle (1–2)

- How do you decide what counts as “the object” (the system) before you write ?

- When do you need a different model than (e.g., variable mass, rotation, relativistic speeds)?

Between Principles (1 max)

- How is Newton’s First Law a special case of the Second Law?

Generate an Example (1 max)

- Describe a situation where an object moves but . What forces cancel?

Retrieval Practice

Answer from memory, then click to reveal and check. (See Retrieval Practice for the full method.)

State the principle in words: _____The net force on an object equals its mass times its acceleration.

Write the canonical equation: _____

State the canonical condition: _____

Worked Example

Use this worked example to practice Self-Explanation.

Problem

A 5.0 kg block rests on a horizontal frictionless surface. A horizontal force of 20 N is applied to the block. What is the block’s acceleration?

Step 1: Verbal Decoding

Target:

Given: ,

Constraints: frictionless surface

Step 2: Visual Decoding

Try drawing a free-body diagram of the block. Include all forces and their directions. Choose axes: right, up.

Step 3: Physics Modeling

Step 4: Mathematical Procedures

Step 5: Reflection

- Units: ✓

- Magnitude: Bigger force → bigger acceleration; bigger mass → smaller acceleration ✓

- Limiting case: If force were zero, acceleration would be zero (Newton’s First Law) ✓

Before moving on: self-explain the model

Try explaining Step 3 out loud (or in writing): why the net force is what matters, why we split into components, and why here.

Physics model with explanation (what “good” sounds like)

Principle: Newton’s Second Law for Translation, .

Conditions: Inertial lab frame; speeds are non-relativistic; mass is constant; we model translation of the block.

Relevance: Forces determine acceleration. Because forces act in different directions, we use the vector form and/or component equations.

Description: The free-body diagram identifies horizontally, and and vertically. Since the block doesn’t move vertically, vertical forces cancel and . Horizontally, the net force equals the applied force, so the acceleration is constant and points right.

Goal: Convert the situation into (and to justify no vertical acceleration), then solve for .

Solve a Problem

Apply what you’ve learned with Problem Solving.

Problem

A 10 kg crate sits on a horizontal surface with coefficient of kinetic friction . A horizontal force of 40 N is applied to the crate. What is the crate’s acceleration?

Hint: Don’t forget friction opposes motion. You’ll need both the x-component equation and the y-component equation to find the normal force first.

Show Solution

Step 1: Verbal Decoding

Target:

Given: , ,

Constraints: horizontal surface, kinetic friction

Step 2: Visual Decoding

Try drawing a free-body diagram: block with right, left, up, down. Choose axes: right, up.

Step 3: Physics Modeling

Step 4: Mathematical Procedures

Step 5: Reflection

- Units: ✓

- Magnitude: Friction reduces net force from 40 N to 15.5 N, giving smaller acceleration than the frictionless case. ✓

- Limiting case: If , we get (matches worked example). ✓

Related Principles

| Principle | Relationship to Newton’s Second Law |

|---|---|

| Newton’s First Law | Special case where (equilibrium). |

| Newton’s Third Law | Describes force pairs between objects; Second Law describes motion of each object. |

| Impulse-Momentum Theorem | Derived by integrating Newton’s Second Law over time. |

| Conservation of Linear Momentum | Falls out when external impulse is negligible (system level). |

Next Step in Mechanics Core

- Next: Newton’s Third Law — interaction pairs (fixes FBD mistakes)

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Newton’s Second Law in simple terms?

Newton’s Second Law states that the net force on an object equals its mass times its acceleration (). In simple terms: push harder → more acceleration; heavier object → less acceleration for the same push.

Why do we use the sum of forces, not individual forces?

Newton’s Second Law relates the total (net) force to acceleration. Each individual force contributes to the net force, but only the vector sum determines how the object accelerates. Applying to each force separately is meaningless.

Does Newton’s Second Law work in all reference frames?

No. It only works in inertial (non-accelerating) reference frames. In accelerating or rotating frames, you must add fictitious forces (like centrifugal force) to make the law work.

What’s the difference between mass and weight in Newton’s Second Law?

Mass () is an intrinsic property measured in kg—it appears as the proportionality constant in . Weight is a force (specifically, the gravitational force ) measured in newtons. Weight is one of the forces you sum when applying the Second Law.

When does Newton’s Second Law break down?

It breaks down at speeds approaching the speed of light (relativistic regime) and in non-inertial reference frames (unless you account for fictitious forces). For everyday problems—cars, projectiles, blocks on inclines—it applies perfectly.

How is Newton’s Second Law different from the First Law?

Newton’s First Law is the special case of the Second Law where the net force is zero: if , then (object at rest or constant velocity). The Second Law generalizes this to any net force.

What does “for translation” mean in Newton’s Second Law for Translation?

“For translation” means this form applies to the motion of an object’s center of mass (straight-line or curved path motion). For rotation about an axis, you need the rotational analog: (net torque equals moment of inertia times angular acceleration).

How This Fits in Unisium

Newton’s Second Law is a representational principle in Unisium—a fundamental equation that connects observable quantities (forces, mass, acceleration). When you solve a mechanics problem in Unisium, the app tracks whether you’ve identified the correct representational principle for the situation. Mastering this law means more than memorizing —it means knowing when it applies, how to set up free-body diagrams, and why the vector nature matters.

Ready to practice Newton’s Second Law with spaced repetition and immediate feedback? Start learning in the Unisium app or explore the research behind our approach in Masterful Learning.

Masterful Learning

The study system for physics, math, & programming that works: encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, principled problem solving, and more.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →