Newton's First Law for Translation: When Forces Balance

Newton’s First Law for Translation, also known as the Law of Inertia, states that an object will remain at rest or move at a constant velocity unless acted upon by a net external force. In practice, if you can model the situation in an inertial frame and acceleration is zero, your free-body diagram must sum to the zero vector.

Using Newton’s First Law well means spotting when acceleration is zero, choosing an inertial frame, and drawing a free-body diagram where forces cancel as vectors. It requires more than memorizing a definition—you must learn to identify hidden forces and understand the vector nature of equilibrium.

On this page: The Principle · Conditions · Misconceptions · EE Questions · Retrieval Practice · Worked Example · Solve a Problem · FAQ

The Principle

Statement

Newton’s First Law for Translation states that an object at rest stays at rest, and an object in motion stays in motion with a constant velocity (constant speed in a straight line), unless acted upon by a net external force. This property of objects to resist changes in their state of motion is called inertia.

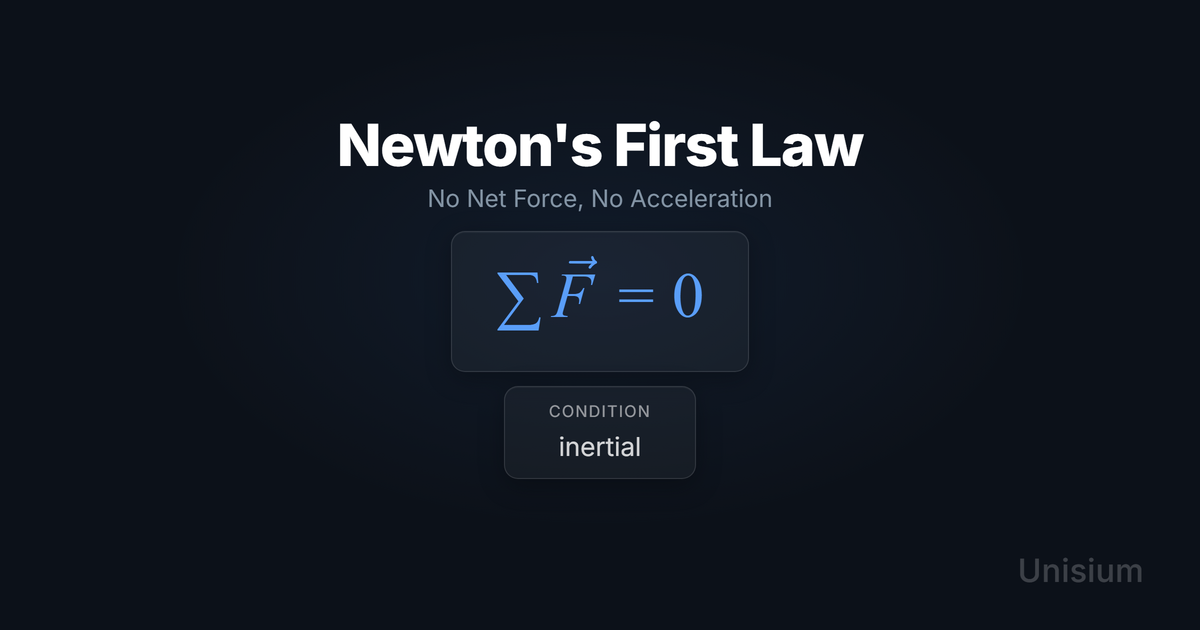

Mathematical Form

Where:

- = net force (the vector sum of all external forces acting on the object), measured in newtons (N).

- “External” = forces on the object from other objects, not forces the object exerts.

- = zero vector, indicating that forces in all directions must cancel out

Alternative Forms

In different contexts, this appears as:

- Component form: and

- Scalar form (one-dimensional):

Conditions of Applicability

Condition: inertial

Practical modeling notes

- Inertial reference frame: In accelerating frames, you must add inertial (pseudo) forces or switch to a non-accelerating frame.

- Translational equilibrium: This form of the law applies to the motion of the center of mass.

- Constant velocity: The condition means the velocity is constant. This includes both objects at rest () and objects moving at a steady speed in a straight line.

When this isn’t the right tool

- Accelerating objects: If an object is speeding up, slowing down, or changing direction, use Newton’s Second Law instead (). In collisions or rapid impacts, consider Impulse–Momentum or Conservation of Linear Momentum.

- Non-inertial frames: In a rotating or accelerating system, you must add inertial (pseudo) forces or switch to a non-accelerating frame.

- Relativistic speeds: At speeds approaching the speed of light, use relativistic dynamics to relate force and motion.

The Unisium framework, described in Masterful Learning, teaches you to recognize these boundaries early in the problem-solving process.

Want the complete framework behind this guide? Read Masterful Learning.

Common Misconceptions

Misconception 1: “Force is required to keep an object moving”

The truth: No net force is required to maintain a constant velocity. Forces like friction or air resistance usually slow things down on Earth, making it seem like we need to keep pushing, but in the absence of those forces, an object would glide forever. This confusion disappears if you compare with Newton’s Second Law (force causes acceleration, not velocity).

Why this matters: Students often invent a “forward force” in their free-body diagrams for objects moving at constant speed. If the velocity is constant, the net force must be zero.

Misconception 2: “Inertia is a force”

The truth: Inertia is a property of matter (related to its mass), not a force. It is the tendency of an object to resist acceleration.

Why this matters: You should never draw an “inertia force” on a free-body diagram. Forces must come from a physical interaction with another object.

Elaborative Encoding

Use these questions to build deep understanding. (See Elaborative Encoding for the full method.)

Within the Principle

- What is the difference between an individual force and the net force ? Why can an object have five forces acting on it but still follow ?

- Why is it necessary to specify “constant velocity” rather than just “constant speed” in the statement of the law?

For the Principle

- If you see an object moving in a perfect circle at a constant speed, does Newton’s First Law apply? Why or why not?

- How do you verify if a reference frame is “inertial” before applying this principle?

Between Principles

- How does Newton’s First Law relate to Newton’s Second Law?

Generate an Example

- Describe a situation where a person feels a “push” even though no physical object is pushing them. How does this demonstrate the limits of Newton’s First Law in non-inertial frames?

Retrieval Practice

Answer from memory, then click to reveal and check. (See Retrieval Practice for the full method.)

State the principle in words: _____An object remains at rest or constant velocity unless acted on by a net external force.

Write the canonical equation: _____

State the canonical condition: _____inertial

Worked Example

Use this worked example to practice Self-Explanation.

Problem

A 10 kg crate is being pulled across a horizontal floor at a constant velocity of 2.0 m/s by a horizontal rope. The coefficient of kinetic friction between the crate and the floor is 0.30. Find the tension in the rope.

Step 1: Verbal Decoding

Target:

Given:

Constraints: horizontal floor, constant velocity, kinetic friction

Step 2: Visual Decoding

Try drawing a free-body diagram of the crate. Label the tension, friction, normal force, and weight. Choose right and up. Mark friction to the left and weight downward. (So is negative in , and is negative in .)

Step 3: Physics Modeling

Step 4: Mathematical Procedures

Step 5: Reflection

- Units: . Correct.

- Magnitude: The tension (29.4 N) exactly matches the friction force ( N), which is expected for equilibrium at constant velocity.

- Limiting case: If the floor were frictionless (), the tension required to maintain constant velocity would be zero.

Before moving on: self-explain the model

Try explaining Step 3 out loud: Why is the sum of forces in the x-direction equal to zero even though the crate is moving? How does the vertical equilibrium help us find the horizontal friction?

Physics model with explanation (what “good” sounds like)

Principle: Newton’s First Law for Translation ().

Conditions: The problem states “constant velocity,” which implies .

Relevance: Because the crate is not accelerating, all forces must be balanced. This allows us to set the sum of horizontal forces and the sum of vertical forces to zero independently.

Description: Vertically, the floor pushes up (normal force) to balance gravity (weight). This normal force determines the strength of the kinetic friction opposing the motion. Horizontally, the rope must pull forward with exactly enough force to cancel out this friction.

Goal: Use the vertical equilibrium to find , then substitute this into the horizontal equilibrium equation to solve for the tension .

Solve a Problem

Apply what you’ve learned with Problem Solving.

Problem

A 5.0 kg lamp hangs motionless from a ceiling by a vertical cable. What is the tension in the cable?

Hint: Identify the two forces acting on the lamp and their directions.

Show Solution

Step 1: Verbal Decoding

Target:

Given:

Constraints: motionless, vertical cable

Step 2: Visual Decoding

Try drawing a free-body diagram of the lamp. Label the tension and weight. Choose up. Mark weight downward. (So is negative in .)

Step 3: Physics Modeling

Step 4: Mathematical Procedures

Step 5: Reflection

- Units: . Correct.

- Magnitude: The tension (49 N) matches the weight ( N), which is expected for an object at rest.

- Limiting case: If , . Correct.

Related Principles

| Principle | Relationship to Newton’s First Law |

|---|---|

| Newton’s Second Law | The general case where ; the First Law is the case where . |

| Newton’s Third Law | Explains where forces come from and why you don’t cancel action-reaction pairs on a single object. |

| Impulse-Momentum Theorem | Used if the force acts over time to change the state of motion (momentum). |

| Conservation of Linear Momentum | A system-level shortcut for analyzing collisions or recoil when external forces are balanced. |

See Principle Structures for how to organize these relationships visually.

Next Step in Mechanics Core

- Next: Newton’s Second Law — general engine: net force → acceleration

FAQ

What is Newton’s First Law?

Newton’s First Law, or the Law of Inertia, states that an object’s motion won’t change unless a net force acts on it. If it’s at rest, it stays at rest. If it’s moving, it keeps moving at the same speed and in the same direction.

What is inertia?

Inertia is the natural tendency of objects to resist changes in their motion. It is not a force, but a property of matter. The more mass an object has, the more inertia it has.

What does “equilibrium” mean in physics?

Equilibrium occurs when the net force on an object is zero (). This means all individual forces acting on the object cancel each other out, resulting in zero acceleration.

If an object is moving, doesn’t that mean there’s a net force?

No. An object moving at a constant velocity has a net force of zero. A net force is only required to change velocity (to accelerate).

How do I know when to use Newton’s First Law vs. the Second Law?

Use the First Law if the problem states the object is “at rest,” “motionless,” “at constant velocity,” or “in equilibrium.” Use the Second Law if the object is accelerating.

Related Guides

- Principle Structures — Organize this principle in a hierarchical framework

- Newton’s Second Law — The generalization of force and motion

- Self-Explanation — Learn to explain worked examples step by step

- Problem Solving — Apply principles systematically to new problems

How This Fits in Unisium

Newton’s First Law is a fundamental representational principle in the Unisium Study System. It serves as the entry point for force analysis, teaching students to move from verbal descriptions of “balance” to formal vector equations. In the Unisium app, mastering this law involves practice in identifying when acceleration is zero and correctly constructing free-body diagrams to satisfy the condition.

Ready to master Newton’s First Law? Start practicing with Unisium or explore the full learning framework in Masterful Learning.

Masterful Learning

The study system for physics, math, & programming that works: encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, principled problem solving, and more.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →