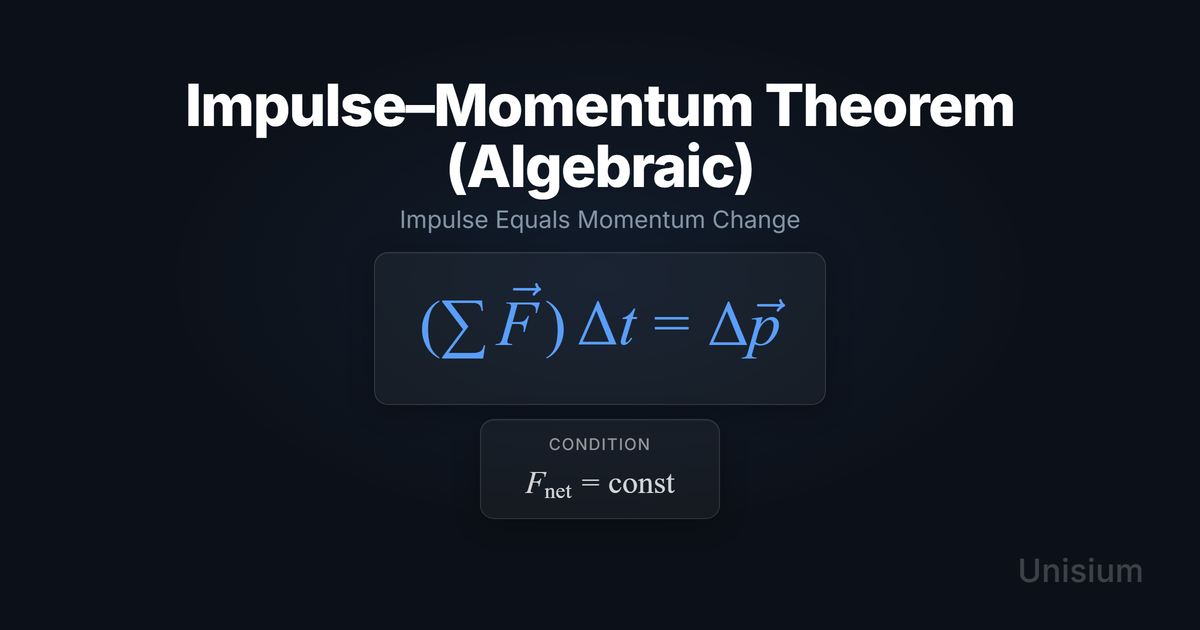

Impulse–Momentum Theorem (Algebraic): Impulse Equals Momentum Change

The Impulse–Momentum Theorem (Algebraic Form) states that impulse (net force times time interval) equals the change in momentum of an object. This relationship follows directly from Newton’s Second Law when integrated over time. Master it by learning the equation and the constant-force condition, then practicing it on collisions and short-force interactions.

This relationship is derived from Newton’s Second Law by integrating over time. Mastering it requires elaboration, retrieval practice, self-explanation, and problem solving—core strategies in the Unisium Study System.

This principle connects Newton’s second law to momentum by integrating force over time. It’s essential for analyzing collisions, impacts, and any scenario where force acts over a measurable duration to change an object’s motion.

On this page: The Principle · Conditions · Misconceptions · EE Questions · Retrieval Practice · Worked Example · Solve a Problem · FAQ

The Principle

Statement

The impulse delivered to an object equals the change in the object’s momentum. Impulse is defined as the net force acting on the object multiplied by the time interval over which that force acts. This relationship follows directly from Newton’s second law when integrated over time.

Mathematical Form

Where:

- = constant net force (N)

- = time interval (s)

- = change in momentum (kg·m/s)

Alternative Forms

In different contexts, this appears as:

- Scalar form:

- Expanded momentum form:

Conditions of Applicability

Condition:

Practical modeling notes (optional)

- The force must remain constant in both magnitude and direction during

- In collision problems, we often use as an approximation or definition of the average force—this is rearranging the impulse-momentum relation, not a separate principle

- For variable forces where you need the exact impulse, use the integral form: (see the Impulse-Momentum Theorem - Integral principle)

When the Algebraic Form Is Unsafe

The impulse-momentum theorem always holds in its integral form . The algebraic form requires constant force.

- Rapidly varying force: If force changes significantly during the interval, the algebraic form cannot be applied directly. You can either use the integral form or work backwards to find the average force via . For collisions, consider the Conservation of Linear Momentum and the impulse approximation.

Want the complete framework behind this guide? Read Masterful Learning.

Common Misconceptions

Misconception 1: Impulse is the same as force

The truth: Impulse is force multiplied by time. A small force acting for a long time can deliver the same impulse as a large force acting briefly.

Why this matters: Students often confuse impulse with instantaneous force, leading to errors when analyzing collisions or calculating momentum changes.

Misconception 2: Heavier objects always experience larger impulses

The truth: Impulse depends on the net force and time interval, not mass directly. Two objects experiencing the same net force for the same duration receive equal impulses, regardless of mass.

Why this matters: This error appears when students assume mass determines impulse rather than recognizing that impulse determines how much momentum changes.

Misconception 3: Impulse only applies to collisions

The truth: The impulse-momentum theorem applies whenever a net force acts over any time interval—pushing a shopping cart, a rocket firing its engines, or braking a car.

Why this matters: Limiting the theorem to collisions causes students to miss its application in steady-force scenarios.

Elaborative Encoding

Use these questions to build deep understanding. (See Elaborative Encoding for the full method.)

Within the Principle (1–2)

- What does it mean that and have the same units (N·s = kg·m/s)? Why must they match dimensionally?

- If you double the time interval while keeping force constant, what happens to the impulse? What happens to the momentum change?

For the Principle (1–2)

- How do you decide whether to use the impulse-momentum theorem versus Newton’s second law directly?

- What information do you need to determine if the “constant force” condition is satisfied?

Between Principles (1 max)

- How does the impulse-momentum theorem relate to conservation of momentum? In a collision with no external impulse, why is total momentum conserved?

Generate an Example (1 max)

- Describe a situation where a large force produces a smaller impulse than a small force. What role does time play?

Retrieval Practice

Answer from memory, then click to reveal and check. (See Retrieval Practice for the full method.)

State the impulse-momentum theorem in words: _____The impulse (net force times time interval) equals the change in momentum of an object.

Write the canonical equation for the algebraic impulse-momentum theorem: _____

State the canonical condition: _____

Worked Example

Use this worked example to practice Self-Explanation.

Problem

A 0.145 kg baseball arrives at a batter traveling horizontally at 40 m/s. The batter hits the ball, and it leaves the bat traveling horizontally in the opposite direction at 50 m/s. The bat is in contact with the ball for 1.0 ms. What is the average force exerted by the bat on the ball?

Step 1: Verbal Decoding

Target:

Given: , , ,

Constraints: horizontal motion, constant contact time, treat bat force as constant during contact

Step 2: Visual Decoding

Draw the ball before and after contact. Draw a 1D axis with in the direction the ball leaves. Label opposite and along . (So is negative and is positive in this coordinate choice.)

Step 3: Physics Modeling

Step 4: Mathematical Procedures

Step 5: Reflection

- Units: ✓

- Magnitude: is comparable to the weight of a 1,300 kg car (). Large, but plausible for a 1 ms impact.

- Limiting case: If with finite momentum change, , consistent with gentle deceleration.

Before moving on: self-explain the model

Before looking back, name the principle you used. Why that one and not Newton’s second law directly? Try explaining Step 3 out loud: what the sign convention implies, what assumptions you made, and how the model equation encodes the momentum change.

Physics model with explanation (what “good” sounds like)

Principle: The impulse-momentum theorem connects the bat’s force (acting over contact time) to the ball’s momentum change.

Conditions: The bat-ball contact involves a rapidly varying force, not a truly constant force. However, we can rearrange the impulse-momentum relation to find the average force: . This is a definition/approximation commonly used in collision problems.

Relevance: We need the force, but we’re given velocities and time—impulse-momentum directly relates these quantities without needing acceleration explicitly.

Description: The ball reverses direction, so is the sum of magnitudes (40 + 50 = 90 m/s). The sign convention makes negative and positive.

Goal: Solve for by rearranging the impulse-momentum equation.

Solve a Problem

Apply what you’ve learned with Problem Solving.

Problem

A 1200 kg car traveling at 25 m/s comes to a complete stop. The brakes apply a constant force for 5.0 s. What is the magnitude of the braking force?

Hint (if needed): Define your positive direction, identify initial and final momenta, then apply the impulse-momentum theorem.

Show Solution

Step 1: Verbal Decoding

Target:

Given: , , ,

Constraints: constant braking force, one-dimensional motion

Step 2: Visual Decoding

Draw the car with a 1D axis. Choose in the direction of initial motion. Label along and . The braking force points opposite . (So and in this coordinate choice.)

Step 3: Physics Modeling

Step 4: Mathematical Procedures

Step 5: Reflection

- Units: ✓

- Magnitude: 6,000 N on a 1200 kg car gives deceleration of 5 m/s², stopping from 25 m/s in 5 s—consistent.

- Limiting case: Longer braking time with same momentum change requires smaller force, matching intuition.

Related Principles

| Principle | Relationship to Impulse-Momentum Theorem |

|---|---|

| Newton’s First Law | Helps address the common confusion of “force needed to keep moving.” |

| Newton’s Second Law | The impulse-momentum theorem is derived by integrating over time. |

| Newton’s Third Law | Explains the source of reciprocal impulses in collisions. |

| Conservation of Momentum | When net external impulse is zero, total momentum is conserved. |

See Principle Structures for how to organize these relationships visually.

Next Step in Mechanics Core

- Next: Conservation of Linear Momentum — system rule when external impulse ≈ 0

FAQ

What is the impulse-momentum theorem?

The impulse-momentum theorem states that impulse (net force times time interval) equals the change in an object’s momentum. The algebraic form is: .

When does the impulse-momentum theorem apply?

The algebraic form applies when net force is constant over the time interval. For varying forces, use the integral form , or calculate the average force from .

What’s the difference between impulse and momentum?

Momentum () is a state quantity—how much “motion” an object has at an instant. Impulse () is a process quantity—how much force was applied over time. Impulse causes momentum to change.

What are the most common mistakes with the impulse-momentum theorem?

Confusing impulse with force, forgetting to include direction (impulse and momentum are vectors), and mishandling sign conventions when objects reverse direction.

How is impulse related to collisions?

During a collision, objects exert forces on each other over a short time interval. The impulse from these forces changes each object’s momentum. If no external impulse acts, total momentum is conserved.

Related Guides

- Principle Structures — Organize this principle in a hierarchical framework

- Self-Explanation — Learn to explain worked examples step by step

- Retrieval Practice — Make this principle instantly accessible

- Problem Solving — Apply principles systematically to new problems

How This Fits in Unisium

Unisium helps you master specific principles like the impulse-momentum theorem through structured practice. Elaborative encoding builds understanding of what each symbol means and when the theorem applies. Retrieval practice ensures you can recall the equation and conditions from memory. Self-explanation and problem solving develop your ability to apply the theorem to new situations.

Ready to master the Impulse-Momentum Theorem? Start practicing with Unisium or explore the full learning framework in Masterful Learning.

Masterful Learning

The study system for physics, math, & programming that works: encoding, retrieval, self-explanation, principled problem solving, and more.

Ready to apply this strategy?

Join Unisium and start implementing these evidence-based learning techniques.

Start Learning with Unisium Read More GuidesWant the complete framework? This guide is from Masterful Learning.

Learn about the book →